From Bench to Bedside: Collaborative Research at HSS

Adapted from an interview in HSS’ Discovery to Recovery research newsletter

Robert N. Hotchkiss, MD

Director of Clinical Research

Hospital for Special Surgery

Lionel B. Ivashkiv, MD

Director of Basic Research

Hospital for Special Surgery

Translating basic findings into new ways of treating and preventing musculoskeletal conditions goes to the heart of Hospital for Special Surgery’s research mission. With more than 16,000 surgeries and over 200,000 patient visits annually, HSS is uniquely positioned to advance discoveries aimed at improving patient care. We recently sat down with Robert N. Hotchkiss, MD, Director of Clinical Research, and Lionel B. Ivashkiv, MD, Director of Basic Research, to discuss the partnership between basic science and clinical research at HSS.

How do basic science and clinical research interrelate at HSS?

Hotchkiss: The best research begins with a good question. For example, a clinician might ask, “What causes osteolysis, or loosening, in total joint replacements?” Or, in basic science, the researcher would say, “I wonder if this new cytokine is prevalent or plays a role in osteolysis?” These kinds of questions form the basis of collaborative research between the clinical and basic sciences at HSS.

In the absence of a clinical problem, basic research can pose questions related to basic biology, but there may not be a more immediate impact on patients’ lives. Similarly, clinicians today who aren’t up to speed on the latest innovations in basic science need help to more fully answer their own clinical questions.

Ivashkiv: In most institutions, the relationship between basic and clinical research hasn’t been an equal partnership. One side hasn’t fully understood the other. The clinician would hire scientists to solve a question, and while the scientists wouldn’t actually understand the disease, they would work to solve it themselves without a clinician’s knowledge of the disease or the healing process. A true partnership includes ideas from both sides, using the strengths of both sides.

Hotchkiss: In order to make optimal use of our capacity to discover and innovate, we are working to bring the two sides together. For example, our physicians have been seeing many cases of arthritis at the base of the thumb, and Assistant Scientist Francisco Valero-Cuevas, PhD, has been interested in thumb coordination in the human hand. So he and Cornell student Madhusudhan Venkadesan devised an instrument that measures the strength and dexterity of the thumb by measuring compressive force. Dr. Lisa Mandl then worked with me to apply this test in a clinical setting. By taking what is ostensibly a basic science/engineering instrument and applying this to arthritic thumbs, we can potentially determine new ways to treat with or without surgery.

The Strength-Dexterity Test, created by Assistant Scientist Francisco Valero-Cuevas, PhD, and Cornell University PhD candidate Madhusudhan Venkadesan, helps HSS physicians determine the compressive force of their patients’ thumbs as part of a clinical study of arthritis involving orthopedic surgeons, rheumatologists, and engineers.

What is being done to enhance the capabilities of our clinical research program?

Hotchkiss: We are revamping and reviewing our clinical research activities with an emphasis on patient safety. Our goal is to create a sustainable, durable infrastructure for clinical research.

Ivashkiv: Now that the basic science side of the equation has an infrastructure in place, we’re looking to take it to the next level. And since the clinical side has traditionally been inhabited by practicefocused physicians doing research on the side, we’re working together to enable more effective and programmatic means of establishing clinical projects by focusing on our strengths and aligning them in the most efficient way. In the next few months, the clinical side of HSS research will be able to access this infrastructure and benefit greatly from it.

Hotchkiss: The thumb study is an example of taking an emerging problem, recognizing it, and applying the spirit of inquiry with the patient as a collaborator. We need to inform the patient that by donating some of their time, letting us collect information about their condition, we can learn about the care of their problem and potentially improve care for others in the future.

Going forward, HSS will be using a team-based approach to research. What are the benefits and challenges of using this approach?

Ivashkiv: On the basic side of science, we’ve formed some interdisciplinary teams in three areas. The first team will be researching arthritis as well as osteolysis (bone loss), which accounts for prosthetic loosening in total joint replacements. The second will focus on bone healing, which is relevant for fractures, postoperative spine fusion, and metabolic bone disease. The third team will look at soft tissue remodeling and tissue engineering.

Each of these teams have clinicians who set the agenda and ask questions, senior academic scientists who advise the lab technicians working on the scientific side, and people within the lab who actually run the lab administratively. If you’re a clinician, you don’t have time to run a lab, so it makes sense that it’s broken down in this particular way.

Hotchkiss: It requires a combination of curiosity, humility, and energy. The ultimate goal is to solve these problems for the benefit of a large number of patients. While it is tempting for a researcher to want quick results in a study serving the needs of a small section of the patient population, the other choice is to answer fundamental questions that may require a longer period of time and more patients.

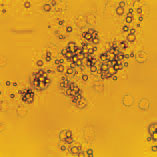

The above image depicts the interaction of cells with implant debris particles that collect around prostheses, leading to osteolysis (bone destruction) and implant loosening. Basic and clinical researchers at HSS have teamed up to investigate the causes of osteolysis with the aim of preventing implant loosening.

What’s unique about this research collaboration at HSS?

Ivashkiv: While it could be said that much of the basic research at HSS is integrated with cutting edge science going on around the world, our distinction lies in our ability to link it to clinical research. HSS is one of the few places where we have this type of access to patients in the clinical population and the ability to ask questions that will have an impact on patients.

We’d like to do something that hasn’t been done before anywhere in the world, which is to take these basic scientific resources and apply them in a meaningful way to asking clinical questions within the confines of musculoskeletal medicine. I think this is the next step that really hasn’t happened anywhere yet.

We’ve also had a lot of success in attracting world-class clinicians while recruiting world-class scientists. I feel that going forward there’s great potential for collaboration, and that’s very exciting.

Where do you see clinical research at HSS in the next five to ten years?

Ivashkiv: We need to bring clinical research up to the state of the art. If we do, I think we’d be among the first musculoskeletal centers to do that. Instead of practitioners doing small projects, we would have a programmatic, team approach of professionals with a rigorous core of methodology that would include clinicians, surgeons, and statisticians – that’s step one.

Step two would be to merge clinical research with this revolution that’s occurring in modern biology and genetics. Today, patients are well-defined and we know what the individual diseases are. However, modern cellular and molecular biology hasn’t been applied in a clinical sense to musculoskeletal medicine. We have to take advantage of the explosion of information we’ve gotten from the genome in order to study systems, apply them to humans, and really understand genetics and the regulation of genes in a really sophisticated way, on a global level.

Hotchkiss: These days, clinicians spend so much time with patients that we need a dedicated, complementary cohort of clinical investigators, and one of our focus areas should be to attract these people to HSS.

As clinical research grows at HSS, we will have the capability of managing the mechanics of enrolling patients, ensuring privacy of patient data, and remaining compliant with the latest rules and regulations regarding patient safety, especially as we become more expansive with our studies.

Ivashkiv: The real goal – what nobody has been able to do thus far – is to take full advantage of the current scientific revolution and apply it to the patient to understand what goes on with these diseases.

If we have the two sides of research at HSS addressing the aforementioned three focus areas, we’d be the best in the world in these major musculoskeletal areas. I think that’s how we’d take it to the next level – not only in quality and impact on patient care, but also in how we’re recognized around the world.

Summary by Mike Elvin