Femoroacetabular Impingement (FAI) Causes and Treatment Options

Femoroacetabular impingement is a malformation of bone in either the femur or acetabulum of the pelvis which, together, form the hip joint. This condition decreases the hip’s range of motion.

- Anatomy of the hip joint

- What is femoroacetabular impingement?

- What causes femoroacetabular impingement?

- What are the symptoms of femoroacetabular impingement?

- How is femoroacetabular impingement diagnosed?

- What is the treatment for femoroacetabular impingement?

- What is the surgery for femoroacetabular impingement?

- What is the recovery time for arthroscopic hip surgery?

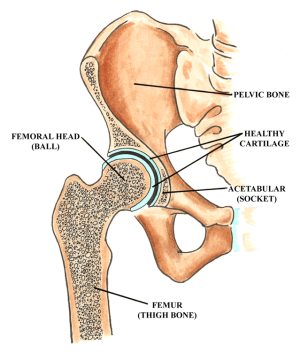

Anatomy of the hip joint

The hip joint (femoroacetabular joint) is a ball-and-socket joint located where the thighbone (femur) meets the pelvic bone. The upper segment (“head”) of the femur is a round ball that fits inside the cavity in the pelvic bone that forms the socket, also known as the acetabulum. The ball is normally held in the socket by very powerful ligaments that form a complete sleeve around the joint capsule.

Both the ball (femoral head) and socket (acetabulum) are covered with a layer of smooth cartilage, each about 1/8 inches thick. The cartilage acts as a sponge to cushion the joint, allowing the bones to slide against each other with very little friction. Additionally, the depth of the acetabulum (socket) is increased by a fibrocartilaginous rim called a labrum that lines the rim of the socket and grips the head of the femur, securing it in the joint by acting through a suction mechanism. The labrum acts as an “o-ring” or a gasket to ensure the fluid in the joint lubricates the cartilage.

Anatomy of the hip

What is femoroacetabular impingement?

Femoroacetabular impingement occurs when portions of the upper femur near the ball of the hip joint (the femoral head) conflict with the hip socket (acetabulum), the labrum and/or the pelvis. Impingement itself is a premature and improper collision or impact between the head and/or neck of the femur and the acetabulum. This causes a decreased range of hip joint motion and hip or groin pain.

What causes femoroacetabular impingement?

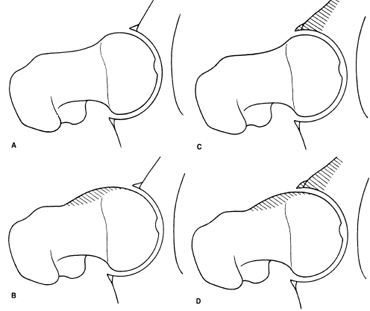

Most commonly, femoroacetabular impingement is a result of excess bone that has formed around the head and/or neck of the femur, (known as “cam”-type impingement). Femoroacetabular impingement also commonly occurs due to overgrowth of the acetabular (socket) rim, otherwise known as “pincer”-type impingement, or when the socket is angled in such a way that abnormal impact occurs between the femur and the rim of the acetabulum. This may cause pain and cartilage or labral injury.

The extra bone that leads to impingement is often the result of normal bone growth and development. Cam impingement is when such development leads to the bump of bone on the femoral head and/or neck.

Normal development can also result in the overgrowth of the acetabular rim, or pincer-type impingement. The tears of the labrum and/or cartilage are often the result of athletic activities that involve repetitive pivoting movements or repetitive hip flexion.

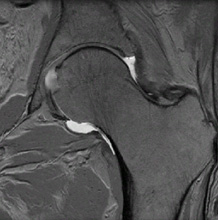

MRI of a normal hip with an intact labrum

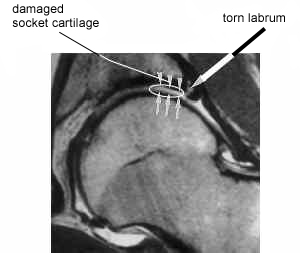

MRI of a hip with a torn labrum

A) Normal Hip B) Cam impingement C) Pincer impingement D) Combination of cam and pincer impingement

Source: Femoroacetabular Impingement Forms - Lavigne, et al.

What happens inside a hip joint that has a femoroacetabular impingement?

When the extra bone on the femoral head and/or neck hits the rim of the acetabulum, the cartilage and labrum that line the acetabulum can be damaged.

The extra bone can appear on X-rays as a seemingly very small “bump.” However, when the bump repeatedly rubs against the cartilage and labrum (which serve to cushion the impact between the ball and socket), the cartilage and labrum can fray or tear, resulting in pain. As more cartilage and labrum is lost, the bone of the femur will impact with the bone of the pelvis. This “bone on bone” notion is most commonly known as arthritis.

Tears of the labrum can also fold into the joint space, further restricting motion of the hip and causing additional pain. This is similar to what occurs in the knee of someone with a torn meniscus.

What are the symptoms of femoroacetabular impingement?

The key symptoms are pain in the hip or groin and a sensation of catching or sharpness during movement. The pain is often a consistent dull ache, which can also be felt along the side of the thigh and in the buttocks. Many people first notice pain in the front of their hip (groin) after prolonged sitting or exercise.

Femoroacetabular impingement symptoms can present at any time between a person's teenage years and middle age.

How is femoroacetabular impingement diagnosed?

Medical imagery in the form of X-ray and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are crucial for diagnosing femoroacetabular impingement. X-ray can reveal an excess of bone on the femoral head or neck, and on the acetabular rim. An MRI can reveal fraying or tears of the cartilage and labrum. A CT scan will also be necessary to confirm the diagnosis.

What is the treatment for femoroacetabular impingement?

Nonsurgical treatment should be tried first, and this may include rest and activity modification , physical therapy and/or anti-inflammatory medications. This often successfully reduces the pain and swelling in the joint.

If pain persists, it is sometimes necessary to differentiate between pain radiating from the hip joint and pain radiating from the lower back or abdomen. A proven method for differentiating between the two is by injecting the hip with a corticosteroid and analgesic.

This hip injection accomplishes two things: First, if the pain is indeed coming from the hip joint the injection provides the patient with pain relief. Secondly, the injection serves to confirm the diagnosis. If the pain is a result of femoroacetabular impingement, a hip injection that relieves pain confirms that the pain is from the hip and not from the back.

What is the surgery for femoroacetabular impingement?

If conservative measures and injection therapy does not adequately treat the symptoms of femoroacetabular impingement, arthroscopic hip surgery may be advised.

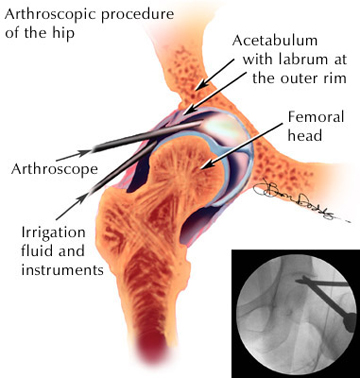

Arthroscopic hip surgery for treating femoroacetabular impingement

In this type of hip surgery (also called hip arthroscopy or a “hip scope”), surgery is performed on the hip joint using an arthroscope. An arthroscope is a long, thin flexible, fiberoptic tool fixed with a small camera that allows an orthopedic surgeon to view the inside of a joint. Specially designed arthroscopic surgical tools are also used to perform minimally invasive joint surgery.

This advancement in surgical technology has allowed orthopedic surgeons to treat conditions that were previously were either ignored or treated with an “open” procedure, which involves larger incisions and longer recovery times.

Arthroscopy of the hip joint was developed in the 1970s and further refined in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Today, arthroscopic hip surgery is a common procedure to manage femoroacetabular impingement.

What happens during arthroscopy of the hip?

Arthroscopic hip surgery is a minimally invasive procedure. The use of an arthroscope means that the procedure is done using two to three small incisions − each approximately 1/4" to 1/2" ( 0.6 cm to 1.5 cm) long. These small incisions, or “portals", are used to insert the surgical instruments into the joint.

Aiding other advances in arthroscope technology, saline fluid will flow through the joint during the procedure, irrigating and expanding it to provide the surgeon with a better view. The surgeon’s visualization of the joint is also aided by fluoroscopy, a portable X-ray apparatus used during the surgery so that the surgeon can see that the instruments and arthroscope are inserted properly.

.

A patient being set up for traction

The location of the incisions and instruments for the procedure

The instruments include an arthroscope and a variety of “shavers” that allow the surgeon to debride (cut away) the frayed cartilage or labrum that is causing the pain. The shaver is also used to shave away any bumps of bone that are responsible for damage to the cartilage or labrum. The labrum can be re-attached to the bone when it is injured using a variety of suture techniques.

In addition to removing frayed tissue and loose bodies within the joint, occasionally holes may be drilled into patches of bare bone where the cartilage has been lost. This technique is called "microfracture" and stimulates the formation of new cartilage where it has been lost.

Hip arthroscopy is normally done as an outpatient surgery, which means the patient has the surgery in the morning and can go home that same day. Normally, the patient is under regional anesthesia. Under regional anesthesia, the patient is numbed only from the waist down and does not require a breathing tube.

What is the recovery time for arthroscopic hip surgery?

Patients will normally use crutches for the first week or two to minimize weightbearing, followed by six weeks of physical therapy. It may take four to six months before they can return to vigorous, unrestricted exercise.

A postoperative appointment is normally held two weeks after the surgery to remove sutures. Following this appointment, the patient normally begins a physical therapy regimen that improves strength and flexibility in the hip.

After six weeks of physical therapy, many patients can start to resume normal activities, but it may take four to six months to start participating in more strenuous exercise or sports. As no two patients are the same, regular post-operative appointments with one’s surgeon is necessary to formulate the best possible recovery plan.

What are the possible complications of arthroscopic hip surgery?

As with all surgical procedures, there remains a small likelihood of complications associated with hip arthroscopy. Some of the risks are related to the use of traction. Traction is required to distract and open up the hip joint to allow for the insertion of surgical instruments. This can lead to post-surgery muscle and soft tissue pain, particularly around the hip and thigh. Temporary numbness in the groin and/or thigh can also result from prolonged traction. Additionally, there are certain neurovascular structures around the hip joint that can be injured during surgery, as well as a chance of a poor reaction to the anesthesia.

Who will benefit from arthroscopic hip surgery?

Patients who respond best to hip arthroscopy are active individuals with hip pain, where there exists an opportunity to preserve the amount of cartilage they still have.

Following a combination of physical and diagnostic exams, patients are deemed suitable for hip arthroscopy on a case-by-case basis. Patients who have already suffered significant cartilage loss in the joint may be better suited to have a more extensive operation, which may include a hip replacement.

Studies have shown that 85% to 90% of hip arthroscopy patients return to sports and other physical activities at the level they were at before their onset of hip pain and impingement. The majority of patients clearly get better, but it is not yet clear to what extent the procedure stops the course of arthritis. Patients who have underlying skeletal deformities or degenerative conditions may not experience as much relief from the procedure as would a patient with simple femoroacetabular impingement.

Conclusion

Arthroscopic hip surgery is indicated when conservative measures fail to relieve symptoms related to femoroacetabular impingement, a condition that has been poorly understood and under-treated in the past. Advances have made hip arthroscopy a safe and effective alternative to open surgery of the hip, a tremendous advantage in treating early hip conditions that ultimately can advance to end-stage arthritis. Hospital for Special Surgery hip surgeons have the special training and high volume of experience to perform hip arthroscopy skillfully and with documented successful outcome.

Updated: 9/21/2021

Authors

Attending Orthopedic Surgeon, Hospital for Special Surgery

Associate Professor of Clinical Orthopedic Surgery, Weill Cornell Medical College

Chief, Hip Preservation Service, Hospital for Special Surgery

Attending Orthopedic Surgeon, Hospital for Special Surgery