An Overview of Lower Back Pain

Most people will experience some form of lower back pain in their lives. About 97% of back pain is caused by a mechanical issue and will get better quickly. But other potential causes must be considered early on, because many of these require very specific nonsurgical or surgical treatment. Careful, early attention to obtain the correct diagnosis will maximize the success of the treatment chosen for the individual patient.

When back pain is associated with fever, loss of leg sensation or strength or difficulty with urination, quick medical attention is required. In cases where back pain is related to a mechanical problem, patients can exercise and learn lifting and movement techniques for prevention of future episodes.

Multiple pain management procedures such as epidural steroid injections (corticosteroids) are available, and a number of types of surgical procedures are available for people where conservative measures are not effective.

How common is lower back pain?

Two out of every three adults suffer from low back pain at some time. Back pain is the #2 reason adults visit a doctor and the #1 reason for orthopedic visits. It keeps people home from work and interferes with routine daily activities, recreation, and exercise. The good news is that for 9 out of 10 patients with low back pain, the pain is acute, meaning it is short-term and goes away within a few days or weeks. There are cases of low back pain, however, that take much longer to improve, and some that need evaluation for a possible cause other than muscle strain or arthritis.

Symptoms may range from muscle ache to shooting or stabbing pain, limited flexibility and/or range of motion, or an inability to stand straight.

What structures make up the back?

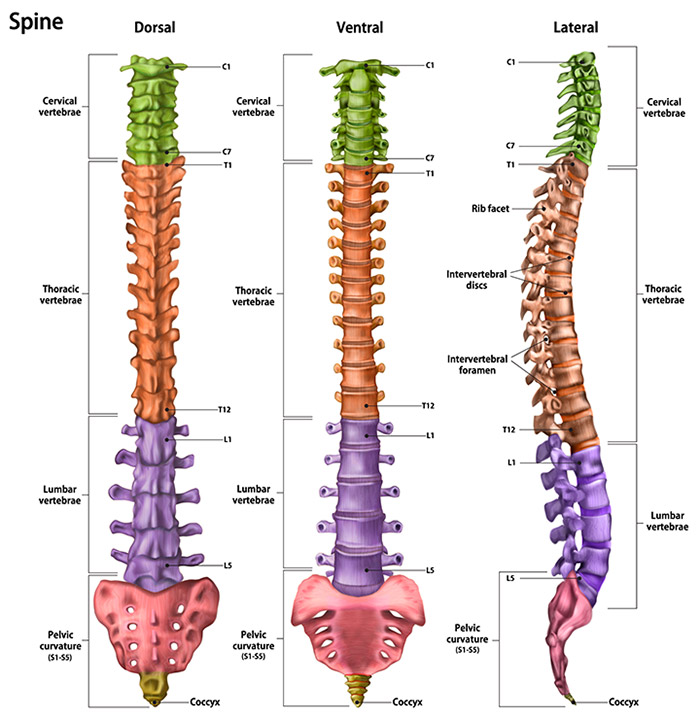

The back is an intricate structure of bones, muscles, and other tissues that form the back, or posterior part of the body’s trunk, from the neck to the pelvis. At the center is the spinal column, which not only supports the upper body’s weight but houses and protects the spinal cord – the delicate nervous system structure that carries signals that control the body’s movements and convey its sensations. Stacked on top of one another are about 30 bones – the vertebrae – that form the spinal column, also known as the spine. Each of these bones contains a roundish hole that, when stacked in line with all the others, creates a channel that surrounds the spinal cord. The spinal cord descends from the base of the brain and extends (in the adult) to just below the rib cage.1

Vertebrae are bones that form the spinal column. Small nerves (“roots”) enter and exit from the spinal cord through spaces between these vertebrae. Because the bones of the spinal column continue growing long after the spinal cord reaches its full length in early childhood, the nerve roots to the lower back and legs extend many inches down the spinal column before exiting. This large bundle of nerve roots is referred to as the cauda equina (horse’s tail). The spaces between the vertebrae are maintained by round, spongy pads of cartilage called intervertebral discs. They allow for flexibility in the lower back and act as shock absorbers throughout the spinal column to cushion the bones as the body moves. Ligaments and tendons hold the vertebrae in place and attach the muscles to the spinal column.2

Starting at the top, the spine has four vertebral regions:

- Seven cervical or neck vertebrae (labeled C1-C7)

- Twelve thoracic or upper back vertebrae (labeled T1-T12)

- Five lumbar vertebrae (labeled L1-L5), known as the lower back

- The sacrum and coccyx, a group of bones fused together at the base of the spine.

What are the causes of lower back pain?

The vast majority of patients experience back pain because of mechanical reasons. They strain a muscle from heavy lifting or twisting, suffer a sudden jolt in a car accident, experience stress on spinal bones and tissues resulting in a herniated disc, or suffer from spondylosis (osteoarthritis of the spine), a potentially painful degeneration of one or more spinal joints. Common causes for low back pain are:

- mechanical or functional injury (causes 97% of cases)

- inflammation

- fracture

- active infection

- neoplasms (tumors)

- referred pain (pain from one location felt in another, such as pain from a kidney stone radiating down the lower back or around to the abdomen)

To choose the safest and most effective therapy, doctors need to consider the full spectrum of possible underlying issues, such as inflammatory conditions, fracture, infection, as well as some serious conditions unrelated to the back that radiate pain to the back.

What type of doctor should I see for back pain?

This depends on your condition or symptoms. If you have no obvious injury that would explain your pain, you may want to start by seeing a physiatrist. This is a specialist in physical medicine who can diagnose back pain and determine whether nonsurgical treatments such as physical therapy may help. Depending on those findings, a physiatrist may also refer you to a spine surgeon, pain management doctor or other type of back specialist, rheumatologist, for additional discussion.

The importance of an accurate diagnosis

The physician will need to take a careful medical history and do a physical exam to look for certain red flags that indicate the need for an X-ray or other imaging test. In most cases, however, imaging such as X-ray, MRI (magnetic resonance imaging), or CT (computerized tomography) scan is unnecessary.

There may also be certain clues in a patient’s medical history. Low back, nonradiating pain is commonly due to muscle strain and spasm. Pain that radiates into the buttock and down the leg may be due to sciatica (also known as lumbar radiculopathy), a condition in which a bulging (protruding) disc presses on the sciatic nerve, which extends down the spinal column to its exit point in the pelvis and carries nerve fibers to the leg. This nerve compression causes pain in the lower back radiating through the buttocks and down one leg, which can go to below the knee, often combined with localized areas of numbness. In the most extreme cases, the patient experiences weakness in addition to numbness and pain, which suggests the need for quick evaluation.

A persistent shooting or tingling pain may suggest lumbar disc disease. A pain that comes and goes, reaching a peak and then quieting for a minute or two, only to reach a peak again, may suggest an altogether different cause of back pain, such as a kidney stone.

During the physical exam, the doctor may ask the patient to move in certain ways to determine the area affected. For example, the patient may be asked to hyperextend her back, bending backwards for 20 to 30 seconds, to see if that movement causes pain. If it does, spinal stenosis, a narrowing of the canal that runs through the vertebrae and houses the spinal nerves, may be the cause.

When tumor or infection are suspected, the doctor may order blood tests, including a CBC (complete blood count) and sedimentation rate. (An elevated sedimentation rate suggests possible inflammation).

Age and gender issues

Age and gender are important factors to consider when diagnosing low back pain. In a young patient, a benign tumor of the spine called an osteoid osteoma may be the culprit. Inflammatory bowel disease in young people can be connected with spondylitis (inflammation in the spinal joints) and sacroiliitis (inflammation in the sacroiliac joint where the spine meets the pelvis). Low back pain from disc disease or spinal degeneration is more likely to occur as people get older. Conditions such as abdominal aneurysm (a widening of the large artery in the belly) or multiple myeloma (a tumor that can attack bone) are also considered in older individuals.

Osteoporosis and fibromyalgia are much more common triggers of back pain in women than in men. Osteoporosis is a progressive decrease in bone density that leaves the bones brittle, porous and prone to fracture. Fibromyalgia is a chronic disorder that causes widespread musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, and multiple “tender points” in the neck, spine, shoulders, and hips.

Mechanical lower back pain

Because it represents 97% of cases, mechanical low back pain deserves to be discussed first. To determine the factors that bring out the pain, the doctor will consider the following causes of mechanical low back pain:

- Muscle strain.

- Spondylolisthesis (slippage of one vertebral body on the next).

- Herniated disc (the discs, or pads, that act as shock absorbers between the vertebrae can bulge into the space containing the spinal cord or a nerve root and cause pain).

- Osteoarthritis (a common form of arthritis in which the cartilage that cushions the joints breaks down and bony spurs form in the joint, causing pain and swelling).

- Spinal stenosis (caused by a narrowing of the bony canal and predisposes some people to pain related to pressure on the spinal nerves or the spinal cord itself).

Low back pain that gets worse with sitting may indicate a herniated lumbar disc (one of the discs in the lower part of the back). This is because certain positions of the body can change the amount of pressure that an out-of-place disc can press on a nerve. This is one reason we suggest to people with low back pain to periodically get up and stretch or walk around rather than continually stay sitting. Acute onset, that is, pain that comes on suddenly, may suggest a herniated disc or a muscle strain, as opposed to a more gradual onset of pain, which fits more with osteoarthritis, spinal stenosis, or spondylolisthesis.

Inflammatory lower back pain

Although comparatively few patients have low back pain due to a systemic inflammatory condition, the problem can be life long and can impair function significantly. The good news is that treatments can help essentially all patients, and can lead to major improvements.

Seronegative spondyloarthropathies (the classical one being ankylosing spondylitis) are a group of inflammatory diseases that begin at a young age, with gradual onset. Like other inflammatory joint diseases, they are associated with morning stiffness that gets better with exercise. Sometimes fusion of vertebrae in the cervical or lumbar regions of the spine occurs. Drugs called TNF-alpha blocking agents, (such as etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab) which are used for rheumatoid arthritis, are also used to treat the stiffness, pain, and swelling of spondyloarthropathy, when the cases are severe and not responsive to traditional medications

People who have spondyloarthropathy have stiffness that is generally worst in the morning, and have decreased motion of the spine. They also can have decreased ability to take a deep breath due to loss of motion of the chest wall. It’s important for the physician to look for problems with chest wall expansion in patients with spondyloarthropathy.

Treatment for inflammatory back pain includes stretching and strengthening exercises. If there is chest wall involvement, chest physiotherapy is important. Avoiding pillows under the neck when sleeping can help the cervical spine – if it fuses – to fuse in a less debilitating position. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents are useful. In patients with more severe disease, the drugs used are typically sulfasalazine and methotrexate. If the patient is not doing well despite trying these medications, TNF-alpha blockers, appear to provide benefit in such spondyloarthropathies as ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis. Etanercept (Enbrel®), adalimumab (Humira®), infliximab (Remicade®), Golimumab (Simponi®) and certolizumab (Cimzia®) are the five anti-TNF agents presently approved by the FDA for use in this condition. Newer medications, such as secukinumab and ixekizumab, are also effective. These agents clearly improve the patient’s ability to move and function. More study is needed to see whether these medications can prevent fusion of the spine, over the long run, although some studies recently have suggested that they can help prevent further spinal damage.

Reactive arthritis syndrome is one of the forms of spondyloarthropathy. It is a form of arthritis that occurs in reaction to an infection somewhere in the body, and it carries its own set of signs and symptoms. The doctor will look for:

- skin rashes, gastrointestinal or urinary problems, eye inflammation, mouth sores

- joint pain in the arms or legs, in addition to back pain.

- infections (salmonella, Shigella, campylobacter, C. difficile, chlamydia)

Reactive arthritis is treated similarly to ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis, with sulfasalazine and methotrexate, and, if necessary, TNF-alpha blockers or other agents. If there is any clue to infection at the time the arthritis starts, such as infectious diarrhea or infection of the genitourinary tract, these conditions will be treated. However, even with treating the underlying infection, reactive arthritis can continue. This is because reactive arthritis is an inflammatory reaction to an infection, and the inflammation can continue after the infection is gone.

Lower back pain caused by infection

Infections of the spine are not common, but they do occur. The doctor will ask about the usual signs and symptoms of infection, especially when back pain is accompanied by fever and/or chills. Dialysis patients, IV drug users, and patients who have recently had surgery, trauma, or skin infections are at risk for infections of the spine. Infections of the spine can be caused by a number of agents, most commonly bacteria. Doctors will first test for the presence of bacteria, then give antibiotics.

Fractures and lower back pain

Spine fractures are often very difficult pain problems and indicate the possible presence of osteoporosis (a bone disease marked by a progressive loss of bone density and strength, making the bones brittle and vulnerable to breaking). In patients with severe osteoporosis, spinal fractures can occur with no early warning and no significant trauma – the patient does not have to fall to fracture a vertebrae.

Patients with spinal compression fractures experience spasms and, often, very high pain levels.

In patients with low back pain where the cause is difficult to determine, especially for elderly patients with osteoporosis, a fracture in the sacrum (the bone between the two hip bones) may be the cause of the pain. A standard X-ray or bone scan may not show a sacral fracture. Imaging techniques such as CT scan or MRI (magnetic resonance imaging, which depicts both soft tissue and bone) can often reveal these fractures.

It is very important that patients with acute lumbar compression fractures be tested for osteoporosis. A bone density study is needed, unless the patient has no other osteoporosis risk factors and has had a very high impact fracture. Studies have shown that many patients with fractures in the U.S. are discharged from hospitals with no plans for management of their bone density problems, which then are left to worsen.

If osteoporosis is found, many treatments are available, including calcium, vitamin D, and a number of prescription drugs. The variety of agents available to treat osteoporosis is large enough that an agent can generally found for each patient, even if other medical problems make one or another of the agents wrong for them. Once bone density is measured, a decision as to long term osteoporosis management can be made.

Although pain can be very intense, it is best for patients with lumbar fracture to resume activity as soon as possible. This is especially true for elderly patients, who can too easily become weakened, and develop other complications, if mobility is reduced for too long. Opioids (narcotic medications) may be needed for pain control, for as brief a period as possible.

Lower back pain and cancer

Cancer involving the lumbar spine (lower back) is not a common cause of back pain. However, in people who have a prior history of cancer, for example, in the breast or prostate, or who have weight loss or loss of appetite along with back pain cancer needs to be considered.

Night pain can be a clue to cancer in the spine. A benign tumor called osteoid osteoma, which most often affects young people, causes pain that tends to respond well to aspirin. Multiple myeloma is a malignancy that occurs when the plasma cells in the bone marrow begin spreading uncontrollably. It is most common in older people, and can cause pain in many parts of the spine. When tumor or infection are suspected, blood tests may be ordered, including a CBC (complete blood count especially to detect anemia), sedimentation rate (an elevated sedimentation rate indicates inflammation, tumor or infection), and protein electrophoresis (which is a screening test for myeloma).

Referred pain to and from the lumbar spine

Pain in the area of the lumbar spine may be due to important problems that are actually unrelated to the back. Referred pain occurs when a problem in one place in the body causes pain in another place. The pain travels down a nerve.. Sources of referred pain to the low back (and might be confused with a spinal problem) may include abdominal aneurysm (enlarged artery in the belly), tubal pregnancy, kidney stones, pancreatitis, and colon cancer. Clues to these maladies include pain that waxes and wanes over a short period, with frequent peaks of intense pain, weight loss, abnormalities found during abdominal exam, and trace amounts of blood in the urine. On the other hand, pain can be referred from the low back and be felt in another location, as is often the case with sciatica. For example, it is not rare for a patient with a “slipped disc” (disc herniation) in the lower back to have pain in the back of the thigh, or in the calf or even the foot, and not have any low back pain. This situation requires a doctor to sort out the type of pain and to do the examination required to show that the pain is actually coming from the spine (and radiological imaging studies can help to confirm this).

Chronic lower back pain

When back pain continues for more than three months, it is considered chronic. Although for most people an episode of back pain is over by that time, in some cases it progresses and can have a major impact on one’s ability to function. For some patients, physical therapy with local heat or ice application (10 to 15 minutes on and 10 minutes off), combined with a home exercise program and education in proper positions for lifting and other movement techniques can make a major difference. Patients must learn to tolerate a certain degree of pain, or they may allow themselves to become more disabled than necessary. Patients at the Hospital for Special Surgery have had success with “graded exercise” to work through the pain, gradually increasing the exercise quota at each session so they can learn to tolerate more exercise in spite of the pain, and get back to work and activities.

When are diagnostic tests for lower back pain necessary?

Many patients do not need X-rays in the first few weeks of pain because their pain will end up resolving. Many more do not need CT scans or MRI imaging, which are overly sensitive and often reveal abnormalities not related to the patient’s pain. These forms of imaging can be extremely useful, however, if a person has chronic or severe pain, and/or neurological symptoms. Blood tests may be ordered if an infection or tumor is suspected.

X-rays

The Agency for Health Care Policy and Research established guidelines for acute low back pain in 1994. The federal agency suggests there are eight red flags in low back pain that indicate the need for an X-ray:

- patient age is over 50

- history of cancer

- fever or weight loss or elevated ESR

- trauma

- motor deficit

- litigation/compensation

- history of steroid use

- history of drug abuse

These red flags identify patients who are more likely to get infection, cancer or who have a fracture and less likely to have a simple muscle strain. (Litigation compensation was included because Worker’s Compensation cases generally require X-ray.) If none of these red flags exists, an X-ray and other studies may be delayed for one month, during which time 90% of patients with acute back pain will feel better.

MRI or CT scan

The presence of red flags for infection, fracture, or more serious disease will likely require an MRI or CT scan. Also, if symptoms last longer than a month and surgery is being considered, imaging is necessary. When a patient has had prior back surgery, getting imaging beyond that of a simple X-ray is reasonable.

If a patient has signs of cauda equina syndrome, a serious injury to the spinal cord, causing symptoms such as leg weakness, perineal numbness (numbness between the inner thighs) and difficulty urinating), permanent neurological damage may result if this syndrome is left untreated. If clues to this syndrome are present, an MRI, or at minimum, a CT scan, is urgently needed.

There is concern within the medical community that high-tech imaging methods such as MRIs and CT scans, are overused for acute low back pain. Often, these sensitive imaging techniques reveal asymptomatic abnormalities in the lumbar spine that are not the cause of the patient’s pain. In one study, volunteers with no history of back pain were given MRIs and 90% of those over age 60 had degenerative disc disease. An MRI that reveals mechanical abnormalities in the lumbar spine that are causing no symptoms is not helpful.

Blood tests

When tumor or infection are suspected, blood tests may be ordered, including a CBC (complete blood count especially looking for anemia) and sedimentation rate. (An elevated sedimentation rate suggests the presence of inflammation.)

Treatment options for acute lower back pain

Most low back pain is due to muscle strain and spasm and does not require surgery. To treat the pain, medications such as acetaminophen (Tylenol), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents (such as aspirin, naproxen, and ibuprofen), gabapentin or pregabalin can be used. NSAIDs suppress inflammation, pain and fever by inhibiting certain inflammation-causing chemicals in the body. Acetaminophen reduces pain and fever, but does not inhibit inflammation. Gabapentin and pregabalin, medications that have been used for antiseizure activity, also have the ability to block pain. Opioids (such as codeine) provide pain relief and may at times be prescribed to manage severe back pain. However, opioids have many problems, such as habituation, constipation and lightheadedness, and are avoided when possible and used for the shortest possible duration. Epidural injection is an option if the back pain does not respond to these treatments. Each person is different in terms of response to medication.

In contrast with popular wisdom, numerous studies have shown that bed rest beyond two to three days is not helpful. Patients should resume activities as soon as possible. Exercise is an effective way to speed recovery and help strengthen the back and abdominal muscles. Exercise also helps reduce the risk that the back pain will return. Doctors or physical therapists should provide a list of exercises to do at home. It is also important to learn lifting techniques and exercises to reduce worksite injuries. Lumbar corsets are only appropriate if helpful in the work setting. Routine use of lumbar corsets may weaken core strength (spinal and abdominal muscles) and delay recovery. Spinal manipulation can be effective for some patients with acute low back pain.

Other nonsurgical treatments for lower back pain include Intradiscal electrothermal therapy (IDET), nucleoplasty, and radiofrequency lesioning.

Treatment research at HSS

Studies are ongoing at HSS to look at molecular ways to delay or stop degeneration of spinal discs, which can cause chronic back pain, such as the research being conducted by the HSS Spine Development and Regeneration Lab.

Surgery for lower back pain

Because the vast majority of patients recover from their low back pain with little help from a doctor, the rationale behind choosing surgery must be convincing. Eighty percent of patients with sciatica recover eventually without surgery.

Severe progressive nerve problems, bowel or bladder dysfunction and the cauda equina syndrome (described above) make up the most clear-cut indications for back surgery. Back surgery will also be considered if the patient’s signs and symptoms correlate well with studies such as MRI or electromyogram (a diagnostic procedure to assess the electrical activity in a nerve that can detect if muscle weakness results from injury or a problem with the nerves that control that muscle).

In the most serious cases, when the condition does not respond to other therapies, surgery may well be necessary to relieve pain caused by back problems. Some common procedures include:

- Discectomy, such as a microdiscectomy or minimally invasive lumbar discectomy – removal of a portion of a herniated disc

- Spinal fusion – a bone graft that promotes the vertebrae to fuse together

- Spinal laminectomy – removal of the lamina to create more space and reduce irritation and inflammation

Updated: 11/15/2021

Authors

Attending Physician, Hospital for Special Surgery

Professor of Clinical Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College

Related articles

References and useful links

- 1, 2. Excerpted from Low Back Pain Fact Sheet, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health

- Low Back Pain Fact Sheet, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health. Reviewed, July 26, 2003.

- Deyo RA, Weinstein JN, Low Back Pain, N Engl J Med, Vol 344, No. 5, Feb 1, 2001, pp 363-370.