The Achilles tendon is the strongest tendon in the body, linking the heel bone to the calf muscle. Problems with the Achilles are some of the most common conditions seen by sports medicine doctors. Chronic, long-lasting Achilles tendon disorders can range from overuse injuries to tearing of the tendon.

Pain in the heel is often caused by a combination of both acute and chronic problems. These include inflammatory conditions – such as chronic Achilles tendonitis, paratenonitis, insertional Achilles tendonitis and retrocalcaneal bursitis – as well as the degenerative condition known as tendinosis.

- What is paratenonitis?

- What is insertional Achilles tendonitis?

- What is retrocalcaneal bursitis?

- What is Achilles tendinosis?

- How is Achilles tendon pain diagnosed?

- How is Achilles tendon pain treated?

- What's the recovery time for Achilles tendon injuries?

What is paratenonitis?

Paratenonitis is an acute Achilles injury caused by overuse. It involves inflammation of the covering of the Achilles tendon. In really acute cases, the tendon can appear sausage-like, because it is so severely swollen. Marathon runners often experience this type of swelling after long runs.

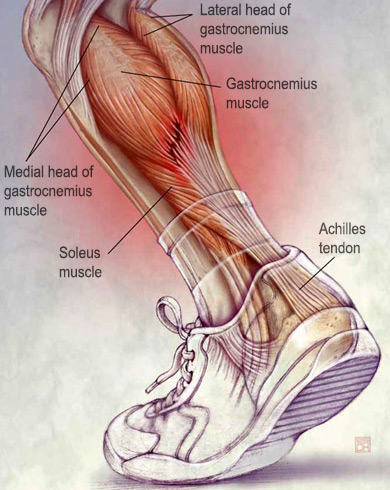

The lower leg muscles and Achilles tendon. (Courtesy of The

Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine. © Steve Oh, CMI 2009.)

Runners may complain of stiffness and discomfort at the beginning of the run, but push through the discomfort. Symptoms are typically aggravated by running and relieved by rest. If left untreated, paratenonitis may progress to the point that any running becomes difficult.

What is insertional Achilles tendonitis?

Insertional tendonitis involves inflammation at the point where the Achilles tendon inserts into the heel bone. People with this condition often have tenderness directly over the insertion of the Achilles tendon, which is commonly associated with calcium formation or a bone spur forming just above the insertion point. This condition can occur along with retrocalcaneal bursitis (see below) and a bony enlargement of the heel bone, known as Haglund’s deformity (and sometimes referred to as a "pump bump"). Most cases of Haglund’s deformity occur in women who wear high-heeled shoes or men and women hockey players because of the skate rubbing on the back of the heel.

What is retrocalcaneal bursitis?

Retrocalcaneal bursitis is caused by movement-related irritation of the retrocalcaneal bursa, the fluid-filled cushioning sac between the heel bone and the Achilles tendon. This condition involves pain in front of the Achilles tendon, in the area between the tendon and the heel bone. The bursa can become inflamed or thickened and stick to the tendon, as a result of overuse or repetitive loading. Pain may result from squeezing the tendon itself or the space just in front of the tendon. Although retrocalcaneal bursitis can be associated with rheumatoid arthritis in 10 percent of people, most occurrences in athletes only involve one side and are not associated with a systemic disease.

What is Achilles tendinosis?

Achilles tendinosis is a degeneration of the Achilles tendon. Most pain in the Achilles tendon may be classified as tendinosis because this pain is related to tendon degeneration rather than inflammation. In addition, the tendon may become weakened and lose its structure. Although aging may play a part in this process, repetitive minor trauma, such as playing sports that involve running or jumping, without proper healing can also play a role. Areas of tendinosis may eventually progress to partial or complete ruptures if they experience high loads, as are seen with physically demanding sports such as football and basketball, especially during push-off and landing activities.

How is Achilles tendon pain diagnosed?

Doctors commonly use ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to evaluate heel pain. These diagnostic methods, along with a physical examination and history, can help sports medicine physicians to properly diagnose Achilles tendon conditions and recommend treatment on an individual basis.

How is Achilles tendon pain treated?

For the distinct disorders above, treatment depends on the nature of the injury. Most people who have injuries related to overuse of the tendon undergo nonsurgical treatment, which begins with rest and modification of activities. Sometimes changing to a cross-training program with bicycling and water therapy can be helpful. A small heel lift that can be inserted within the shoe may be useful in reducing the stress on the Achilles tendon.

In acute cases of Achilles tendon injury, especially when inflammation is involved, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications such as ibuprofen can be beneficial. In addition, treatment involves ice massages, stretching, strengthening exercises and correcting alignment problems under the guidance of a physician, athletic trainer or physical therapist. If these fail to relieve symptoms, injections of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) may be considered, although currently there is limited evidence to support their use. Corticosteroid injections should be used very cautiously as these can weaken the tendon. Other modalities include shockwave therapy, which may potentially incite a healing response in the tendon. A small group of patients who do not benefit from these therapies may require surgery.

How do you prevent Achilles tendon injuries?

Athletes should take the following steps to prevent Achilles tendon injuries:

- Don’t take on too much too fast. Increase the intensity and difficulty of an exercise program gradually so as not to strain your Achilles.

- Use appropriate footwear. The more arch support, the less strain there is on the heel and associated muscles.

- Stretch. Make sure to stretch your Achilles tendon and calf muscles before and after exercise, to keep them loose and reduce the risk of injury.

What is the recovery time for an Achilles tendon injury?

Recovery expectations vary based on the particular injury or combination of injuries that are causing the pain. Based on the results of an ultrasound and MRI, sports medicine physicians will discuss the prognosis on an individual basis. The most important components of an expedient recovery are to rest the Achilles and to modify the exercise regimen to accommodate the pain and issues of overuse.

Paratenonitis recovery

The recovery time for paratenonitis is highly variable and depends on the extent and severity of symptoms, potentially lasting up to or even exceeding three months. Athletes may be able to return to pre-injury levels of play, but this can require an extended period of recovery. While paratenonitis can be resolved with rest and anti-inflammatory medication, it may recur if there are underlying biomechanical factors that contributed to the development of the problem.

Insertional Achilles tendonitis recovery

Athletes should recover within six weeks if the cause of pain is a calcium formation or a bone spur forming just above the insertion point of the Achilles tendon to the heel bone, but recurrence is a risk if the bone spur is not removed.

Retrocalcaneal bursitis recovery

Estimated recovery for retrocalcaneal bursitis is four to six weeks but can be more prolonged, especially if there is an anatomic factor (such as bone spur) that is mechanically irritating the tendon.

Tendinosis recovery

The structural changes that occur in the tendon due to degeneration are largely irreversible, but the symptoms may resolve and thus the athlete may be able to return to play. However, symptoms sometimes recur after activities are resumed.