Bowlegs and Normal Growth and Development of the Legs and Knees

Normal Development of the Legs and Knees

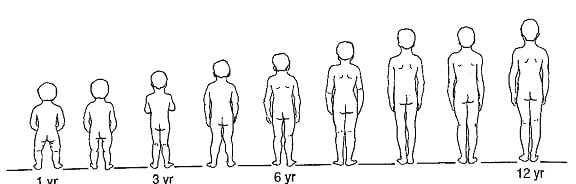

As children grow from toddlers to teenagers, normal alignment changes occur in their legs, so they may appear to be knock kneed or bowlegged. These changes may be of some concern to parents, who may then seek a professional opinion from a pediatric orthopedist. However, most children’s lower extremities follow a predictable pattern.

Here is a chart of the average child’s angular growth:

Illustration by Robert Amaral*

“In almost all cases, this is a benign and natural process and one that does not need treatment or intervention of any kind,” says Julia Munn Hale, PA-C, MHS, Pediatric Orthopaedic Physician Assistant at Hospital for Special Surgery. “It may just require a lot of reassurance of the parents that it is perfectly normal.”

Bowlegs to Knock Knees

Most children are naturally bowlegged when they start to walk. Usually by the age of 2-3 years, the legs start to look more like knock knees. The knock knee phase peaks in the next 1-2 years. After six years of age the knees will normally assume a straighter alignment and there should be very little change in the angular growth. By 12 they have grown into what will be their adult configuration.

When a child’s angular profile (the angle of the thigh bone to the shin bone) or torsional profile (the knee and/or foot pointing straight, inward or outward) falls outside of the normal pattern, or if there is an abnormal profile only on one side (rather than bilateral), further evaluation is sometimes necessary.

Pediatric Orthopedic Evaluations

Concerns about knock knees and bowlegs lead many parents and caregivers to seek professional evaluations. The Pediatric Orthopedist will ask careful questions about the child’s health as well as the developmental and family history. The physician will check the legs thoroughly and watch the patient walk; sometimes x-rays are taken.

Treating a Deformity

If the angulation is extreme or asymmetric (only on one-side), further medical testing or consultation may be required. Medical treatment may be necessary to treat an underlying cause of angular deformities for conditions, such as rickets (which is caused by a vitamin D deficiency). Sometimes bracing or surgery is necessary, particularly for conditions such as Blount’s disease or growth plate injuries.

Damage to the child’s growth plate around the knee (the area of the bone where growth occurs in children) from fracture, injury, or infection can lead to unilateral varus (bowing) or valgus (knock knee). Although 15% to 30% of all childhood fractures affect the growth plate, serious problems due to growth plate injuries are fairly rare – consisting of 1% to 10% of all growth plate injuries - but are of concern nonetheless.

If the deformity is mild, it can be observed and carefully watched with x-rays and pediatric orthopedic exams over time. Surgical treatment may be required if the deformity becomes more pronounced. The type of surgery depends on the nature of the deformity as well as the age of the child.