A Rare Case of VEXAS Syndrome Presenting as an Overlap of Pustular IgA Vasculitis, Sweet’s Syndrome, and Relapsing Polychondritis in a 62-Year-Old Man

From Grand Rounds from HSS: Management of Complex Cases | Volume 13, Issue 3

Case Report

A 62-year-old man with a history of hypertension, deep venous thrombosis (DVT) of the left lower extremity, and vasculitis was admitted with a diffuse rash.

Two years prior, he experienced recurrent unilateral ear swelling and erythema, migrating pain, unilateral eye redness, low blood counts, and occasional redness and pain on his nose. He later developed an upper- and lower-extremity rash that was diagnosed as vasculitis. Although symptoms improved significantly on prednisone 20 mg twice daily, the rash recurred when the dose was reduced to 10 mg daily, and azathioprine was added and titrated up to 100 mg daily. Six months before admission, he developed an unprovoked left lower-extremity DVT and was treated with apixaban.

Two months before admission, the patient developed purpuric rash on the lower extremities, progressing to the upper extremities and back over 6 weeks and evolving into hemorrhagic and bullous lesions. He was treated with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) for 1 month without relief and was subsequently hospitalized. He reported no mucosal ulcers, fever, conjunctivitis, cough, dyspnea, joint pain, or recent infections.

Physical examination revealed erythema and tenderness of the right pinna, right leg edema, and polycyclic/annular purpuric plaques with hemorrhagic bullae on the trunk and extremities (Figures 1–3). He had no oral ulcers or synovitis. Laboratory findings included hemoglobin, 6.5 g/dL; mean corpuscular volume, 122 fL; platelet count, 112,000/µL; white blood cell count, 4,650/µL with lymphopenia (470 cells/µL); haptoglobin, <6 mg/dL; lactate dehydrogenase, 253 units/L; erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 45 mm/hr; C-reactive protein, 11.1 mg/dL (normal range, ≤ 0.9 mg/dL); and ferritin, 1788 ng/mL. Urinalysis revealed 5 red blood cells per high power field. Peripheral blood smear indicated left-shifted granulocytes, moderate macrocytic anemia, and thrombocytopenia. Tests from a month prior showed positive antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) at 1:40 and antinuclear antibody at 1:160 with a homogenous speckled pattern. Rheumatoid factor, antibodies to extractable nuclear antigens, p-ANCA, and c-ANCA tests were negative.

Figure 1: Photograph shows diffuse, violaceous, erythematous appearance of right pinna with edema (sparing the non-cartilaginous ear lobes).

Figure 2: Polycyclic/annular purpuric plaques on the patient’s back, with overlying hemorrhagic bullae.

Figure 3: Hemorrhagic bullae were more prominent on the extremities than the trunk.

This combination of presenting signs and symptoms raised concern for several autoimmune disorders, including relapsing polychondritis with renal involvement and vasculitis, and VEXAS (vacuoles, E1 enzyme, X-linked, autoinflammatory, somatic) syndrome. Medication-induced rash from TMP-SMX and azathioprine were thought to be unlikely as glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and thiopurine methyltransferase levels were normal, and infections were ruled out, as blood and urine cultures, HIV test, hepatitis panel, respiratory viral panel, and QuantiFERON gold test were negative.

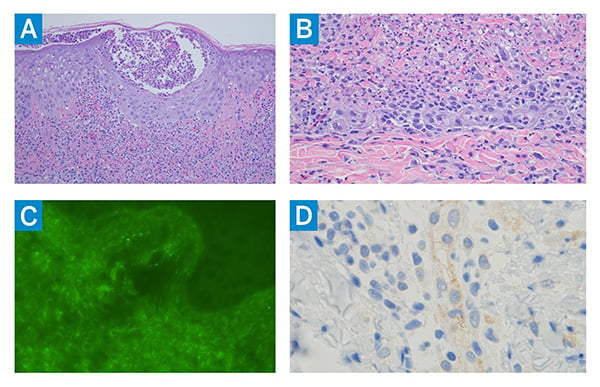

Methylprednisolone IV 1 mg/kg/day was started, with notable improvement in the rash within days. Skin biopsy revealed a prominent neutrophilic infiltrate in the superficial dermis and intraepidermal micro-abscesses composed primarily of neutrophils, with erythrocyte extravasation suggestive of vascular compromise. Direct immunofluorescence studies showed immunoglobulin A (IgA) deposition in the blood vessels of the superficial dermis (Figure 4, a-d). Biopsy findings were consistent with IgA-associated pustular vasculitis (IgAV) with features overlapping with Sweet’s syndrome.

Figure 4: Skin biopsy shows (A) significant intraepidermal pustulation associated with a striking interstitial and perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate, prominent leukocytoclasia, and evidence of vascular compromise in the red cell extravasation, all features of pustular vasculitis (hematoxylin and eosin [H&E] staining, 200×); (B) extensive dermal neutrophilia with accompanying mononuclear cells, leukocytoclastic cells, and an absence of discernible intravascular and vascular mural fibrin deposition, all consistent with a Sweet’s syndrome-like diathesis (H&E staining, 400×); (C) prominent granular deposits of IgA within the microvasculature, consistent with IgA-associated vasculitis (fluorescein-tagged anti-human IgA antibody staining, 400×); and (D) enhanced type I interferon signaling (upregulation of myxovirus-resistance protein A expression) in the endothelium (diaminobenzidine staining, 400×).

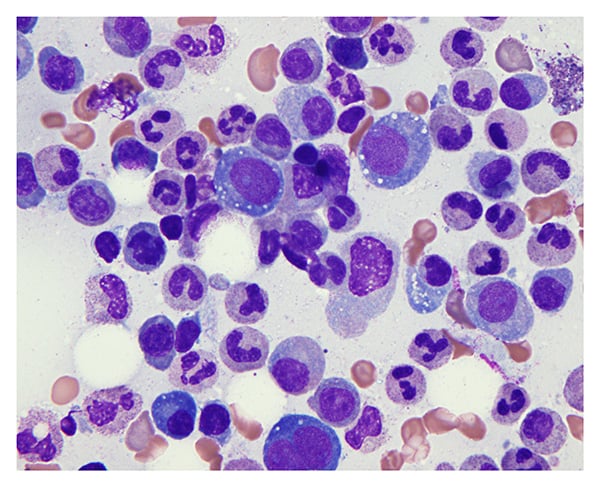

Bone marrow biopsy revealed hypercellularity with granulocytic and megakaryocytic hyperplasia, atypia, and vacuolated myeloid and erythroid elements—findings consistent with VEXAS syndrome (Figure 5). Genetic testing confirmed a VEXAS-associated UBA1 gene mutation.

Figure 5: Bone marrow progenitor cells have prominent cytoplasmic vacuoles characteristic of VEXAS syndrome (Giemsa staining, 400×).

The rash significantly improved, and the patient was discharged after a week on a methylprednisolone taper, and tocilizumab 162 mg subcutaneously every 2 weeks was started in the outpatient setting. After 5 months, he had no recurrence of the rash and cell counts were stable, but he developed cough, dyspnea on exertion, and lung infiltrates, suggesting pulmonary involvement of VEXAS syndrome. Methylprednisolone was maintained at 12 mg per day, and tocilizumab was increased to weekly dosing for better disease control.

Discussion

First described in 2020 [1], VEXAS syndrome is a late-onset, acquired, prototypic hemato-inflammatory disorder primarily affecting men over age 50 that is caused by somatic mutation in the X-chromosome gene UBA1. Dysregulated ubiquitylation leads to overactivation of innate immune pathways, possibly manifesting as recurrent fever, rash, weight loss, eye inflammation, chondritis, lung infiltrates, thrombosis, cytopenia, and predisposition to hematologic malignancy [1–3]. While several types of vasculitis such as polyarteritis nodosa, ANCA-associated vasculitis, and IgA vasculitis have been reported in VEXAS syndrome, and while UBA1 gene mutations have been identified in neutrophilic dermatosis [4], this report presents the first documented case of IgA vasculitis overlapping with Sweet’s syndrome in VEXAS syndrome.

Management of VEXAS syndrome remains challenging; treatments that have shown efficacy include interleukin 1 (IL-1), IL-6, and Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors and azacytidine, with glucocorticoids as temporizing measures [5]. In this patient, methylprednisolone with addition of the IL-6 inhibitor tocilizumab showed some effectiveness. Weekly tocilizumab dosing is aimed at controlling disease, managing pulmonary involvement, and tapering steroids.

This case underscores the importance of a high index of suspicion for VEXAS syndrome in older men presenting with systemic inflammation, cytopenia, and multiorgan involvement. A personalized treatment approach, guided by ongoing monitoring, is essential for optimal patient outcomes.

References

- Beck DB, Ferrada MA, Sikora KA, et al. Somatic mutations in UBA1 and severe adult-onset autoinflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2628-2638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2026834.

- Saad AJ, Patil MK, Cruz N, Lam CS, O'Brien C, Nambudiri VE. VEXAS syndrome: A review of cutaneous findings and treatments in an emerging autoinflammatory disease. Exp Dermatol. 2024;33(3):e15050. doi: 10.1111/exd.15050.

- Pàmies A, Ferràs P, Bellaubí-Pallarés N, Giménez T, Raventós A, Colobran R. VEXAS syndrome: relapsing polychondritis and myelodysplastic syndrome with associated immunoglobulin A vasculitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2022;61(3):e69-e71. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keab782.

- Watanabe R, Kiji M, Hashimoto M. Vasculitis associated with VEXAS syndrome: A literature review. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:983939. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.983939.

- Boyadzhieva Z, Ruffer N, Kötter I, Krusche M. How to treat VEXAS syndrome: a systematic review on effectiveness and safety of current treatment strategies. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2023;62(11):3518-3525. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kead240.