Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: Diagnosis, Treatments and Results

An interview with Drs. Oheneba Boachie-Adjei and Han Jo Kim

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis is the type of scoliosis seen most frequently by spine surgeons and comprises 80% of all spinal deformities.

- What is adolescent idiopathic scoliosis?

- How is it diagnosed?

- How is it treated?

- How does scoliosis surgery work?

- What are the results of spinal fusion surgery?

- What is the expected recovery time?

- FAQs about adolescent idiopathic scoliosis

What is adolescent idiopathic scoliosis?

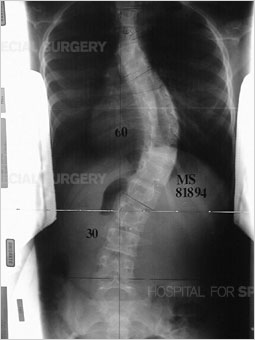

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis a condition in which the spine is curved sideways in one or more areas [Figure 1], with no known cause. This different from that in the condition known as kyphosis, where the spine has an abnormal, forward-oriented curvature [Figure 2]. It affects girls more frequently than boys.

|

|

|

|

Figure 1: Anteroposterior (front to back) view of the spine (standing) demonstrates scoliosis in the thoracic and lumbar spine. |

Figure 2: Lateral (side) view of the spine (standing) demonstrates kyphosis in the thoracic spine. |

Despite its name, the condition does not affect teenagers only. The term "adolescent" is used to apply to all patients whose scoliosis condition is diagnosed when they are between the ages of 10 and 18. Other, non-idiopathic forms of scoliosis can also affect children and teenagers in this age range. These include:

- congenital scoliosis, in which spinal deformities are present from birth

- neuromuscular scoliosis, in which the scoliosis symptomatic of a systemic condition, such as cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, or paralysis

- scoliosis caused by skeletal dysplasia

"Idiopathic means that there is no known cause for this condition," explains Oheneba Boachie-Adjei, MD, Chief Emeritus of the Scoliosis Service. "However," adds Han Jo Kim, MD, Spine Fellowship Director and Fellowship Committee Chair, "research has revealed genetic markers for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis that can show us which curves are likely to progress and require treatment."

How is adolescent idiopathic scoliosis diagnosed?

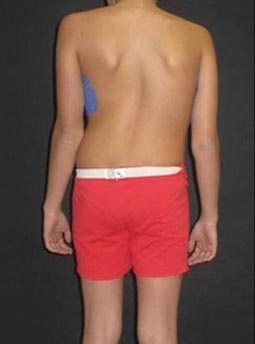

Typically, adolescent idiopathic scoliosis is first noticed by the child’s pediatrician, family member or school nurse. As an initial screening method, healthcare professionals use the Adams forward-bending test to look for the presence of any asymmetry of the torso or shoulder blades, or for protrusion of the shoulder blades [Figure 3].

Figure 3: This photo shows a pronounced curve, revealed during an Adams forward-bending test.

A scoliometer is used to measure the amount of trunk inclination (the curve) or rotation (twisting of the spine). Adolescents with a measurement of 7 degrees or greater are referred to an orthopedist for further evaluation. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis rarely causes pain. For this reason, back pain symptoms in a young person with scoliosis may be a sign of an additional condition.

Radiological imaging

To assess the curve further, X-ray images or low-dose radiation EOS images are taken from the front and side views [Figures 4, 5]. Side-bending X-rays may also be taken to assess the flexibility of the curve or curves. Sometimes these images reveal two curves: the first curve to appear in the spine (the primary curve) and the compensatory curve that the patient develops through his or her effort to maintain an erect posture.

Figures 4 (left) & 5 (right): Anterior to posterior (front to back) and lateral

(side) X-rays showing a scoliosis curve from the back and side, respectively.

How is adolescent idiopathic scoliosis treated?

Treatment for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis determined by the degree of the spinal curve at the time of diagnosis and by the anticipated progression of that curve. Mild cases may not require any treatment at all. More significant cases of this type of scoliosis may be treated nonsurgically, using braces, or with spine surgery, depending on the individual patient. (Find a doctor at HSS who treats scoliosis.)

Non-operative treatment

For curves measuring less than 20 degrees, the orthopedist may recommend frequent monitoring to see if additional intervention becomes necessary.

Young people with curves between 20 and 45 degrees may be candidates for treatment with bracing. While bracing does not correct the curve, it has been shown to stop progression in up to 75% of patients. Bracing is considered a success when progression is halted and maintained within 6 degrees of the original measurement of the curve.

Candidates for bracing are generally younger patients – prepubescent and skeletally immature as measured on the Risser test (a staging system that measures maturation of the hip bone). A measurement of 0 to 2 indicates that the growth is expected to continue. Skeletal maturity is achieved in female patients who reach a level of 4 and in male patients who have reached a level of 5. The absence of any change in height over a period of 6 to 12 months is another indicator of skeletal maturity.

In most cases, patients wear a brace for 22 to 23 hours a day, removing it only for hygiene and sports activities. However, some patients may only require the use of a brace at night.

A variety of braces are available and selection is based on how many curves are present and where on the spine the curve or curves are. Some models provide support at the pelvis, front, back, and neck, where others provide support throughout the torso and underarms.

While many braces are rigid, flexible braces have been developed in recent years. This type of brace, which is only appropriate in patients with single curves, is worn as a vest and allows the patient to participate in some sports activities

Patients continue to wear the brace until skeletal maturity is reached. This allows the supportive muscles in the back and trunk to become stronger after a period of inactivity. Physical therapy is also recommended.

Surgical treatment

Patients with curves that continue to progress beyond 50 degrees, either with or without bracing, generally require surgical intervention.

How does surgery for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis work?

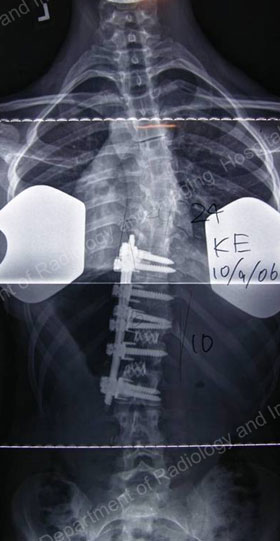

There are different surgical methods, but the most common type of surgery is a posterior spinal fusion with instrumentation (artificial implants). In this procedure, the orthopedic surgeon makes an incision from the back and essentially "welds" the vertebrae together using bone chips.

These bone chips may be:

- autografts – taken from elsewhere in the patient's own body

- allografts – sourced from donors through a bone bank

During the healing process, which takes 6 to 12 months in an adolescent, the spine is held in alignment by hooks, screws or other instrumentation. Once the fusion is complete, the implants no longer serve a function but are left in place to avoid the need for additional surgery [Figures 7 & 8].

Figures 7 (left) & 8 (right): Postsurgical posterior and lateral X-rays of the same patient shown in Figures 4 & 5: results achieved with a posterior approach.

Posterior, anterior and thorascopic surgical approaches

Depending on the nature of the curve and its location, the orthopedic surgeon may need to perform a fusion from the front (anterior), the back (posterior) or both. When both approaches are needed, the procedure may be performed either as a single operation or in stages. Currently, however, this surgery is most commonly performed using a posterior-only procedure.

Figures 9 & 10: Presurgical posterior and anterior X-rays – scoliosis requiring anterior approach.

Figures 11 & 12: Postsurgical posterior (lower left) and lateral (lower right) X-rays – results achieved with an anterior approach.

Some patients may also be candidates for thoracoscopic surgery, in which incisions are made from the side of the torso. As with the posterior and anterior approaches, instrumentation corrects the curve and the rotation of the spine. "The thoracoscopic approach offers the advantages of smaller incisions and shorter fusions, which in turn preserves more mobility in the spine following surgery," Dr. Boachie explains. Thoracoscopic surgery is appropriate primarily for larger and rigid thoracic curves that require anterior release to increase flexibility.

However, Dr. Kim says, "with the introduction of pedicle screws, posterior-only surgery has become the main method of treatment for most curves, large or small."

Vertebral body tethering

A newer approach to treat adolescent idiopathic scoliosis is a non-fusion procedure termed the "tethering" procedure. In Vertebral body tethering (sometimes also called "spinal tethering"), a thoracoscopic approach as described above is performed, and screws are placed within the specific vertebrae. Then, instead of using rods, a thick cord is placed to connect the screws, functioning as a tether. Tension is applied to help a growing child's spine develop with a straighter orientation. Not all patients are candidates for this procedure. Usually, candidacy is dependent on a patient's curve magnitude, age, skeletal maturity and curve type. The results of this procedure have not been researched as extensively as fusion procedures, however, short-term studies demonstrate that it can be successful in selective cases.

Figures 11 & 12: Photos of an adolescent girl with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis

in the thoracic section of the spine, before (left) and after (right) surgery.

What are the results of spinal fusion surgery?

The surgery provides significant spine curvature correction, cosmetic and posture benefits, but does cause some inflexibility in the spine.

Curvature correction

Fusion surgery generally yields very good results, with a correction rate of between 60% to 100%, depending on curve flexibility and location. "These young people, who are usually otherwise healthy, tend to tolerate the surgery very well," says Dr. Boachie. Spinal fusion does result in some loss in range of motion. The extent of that varies depending on the section of spine corrected and the number of vertebrae fused.

Cosmetic results

- A balanced spine

- Reduction of any rib hump

Complications

Rare complications can include infection and spinal cord abnormalities or injury. However, at HSS, multiple precautions are taken during surgery to protect the patient, including administration of antibiotics during surgery to help guard against infection and continuous monitoring of sensory and motor function of the spinal cord.

What is the expected scoliosis surgery recovery time?

Following surgery, most patients remain in the hospital for 3 to 5 days (slightly longer for those who undergo combined anterior/posterior procedures) and are on their feet in two days. Pain medication is continued for a few weeks and the majority of young people are back in school within 4 to 6 weeks. Some exercise, such as swimming and low-impact aerobic exercise, may be resumed within three months and patients may return to full activity within six months. Different Surgeons have different specified approaches to post-operative management.

Frequently asked questions about adolescent idiopathic scoliosis

Q. My 14-year old child was diagnosed with idiopathic scoliosis. The doctor measured her curve as 20 degrees and said her bones are nearly fully grown. She does not have pain and the curve is hardly noticeable but we are concerned. Will it continue to increase and become a big problem later in life?

A. Once your daughter is skeletally mature (when her bone growth is complete), the curvature of the spine from idiopathic scoliosis will not increase. It is unlikely to be a problem, but she should be re-evaluated every 2 to 5 years to monitor the curve progression.

Q. I've heard that electrical stimulation can be used to correct scoliosis. Why doesn't my doctor recommend this?

A. While use of this technique has been reported, there is insufficient clinical evidence to suggest that it offers a benefit to patients with idiopathic scoliosis.

Q. I'm scheduled to undergo surgery for scoliosis and am worried about damage to my nervous system. What are the risks of injury?

A. When performed by experienced orthopedic spine surgeon and surgical team, surgery for scoliosis considered very safe. Maintaining and protecting nervous system function is one of the surgeon’s highest priorities. In general, for uncomplicated adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, the reported risk of nerve injury with surgery is between 0.7% and 1%. In adult patients, the rate of injury ranges between 1% and 5%. Intraoperative spinal cord monitoring will help detect early changes in cord function during surgery.

Q. What are the chances that a 15-year-old teenager who gets scoliosis surgery will need additional surgery later in life?

A. If spine surgery has been properly performed in a teenager, the chance that he or she will require revision surgery in the short- or medium term is very low. More than 98% of patients do well. Surgical complications are quite rare, and most patients leave the hospital within a week after surgery without pain or other problems with wound healing or with the instrumentation used to correct the spinal curve. The need for further surgery in the future will depend on the type of instrumentation that was used and the sagittal (sideways) alignment of the spine.

Location of the area in which instrumentation was placed is also significant. Formerly, revision surgery in the long term was more common in patients with long fusions to the lower portion of the lumbar spine (the vertebrae closest to the pelvis). It appears that the current use of current segmental instrumentation systems that take into account the restoration and maintenance of spinal alignment is reducing the chance that (longer-term) revision surgery will be necessary.

Q. What are the advantages of an anterior versus a posterior scoliosis surgery?

A: The terms anterior (from the front and, sometimes also, side of the body) and posterior (from the patient’s back) refer to the approach the surgeon takes in reaching the area of the spine to be treated. Most curves can be treated with a posterior procedure in which the surgeon uses segmental instrumentation and fusion. This type of surgery generally works best for thoracic curves and for double curves. A posterior approach is easier for the surgeon and offers the advantage of allowing two rods to be placed which obviates the need for external immobilization with a brace or other device. Traditionally, some special curves – such as thoracolumbar and lumbar deformities – have been treated with anterior approach because it offers the advantage of fusing the fewest levels possible, and the ability to derotate the spine and provide three-dimensional correction of spinal deformity. Spine surgeons have applied anterior instrumentation to thoracic curves, but this not a popular practice these days.

Updated: 2/27/2024

Summary by Nancy Novick; images by the HSS Department of Radiology and ImagingAuthors

Attending Orthopedic Surgeon, Hospital for Special Surgery

Professor of Orthopedic Surgery, Weill Cornell Medical College