UCL Injury (Tommy John Injury)

What is the ulnar collateral ligament?

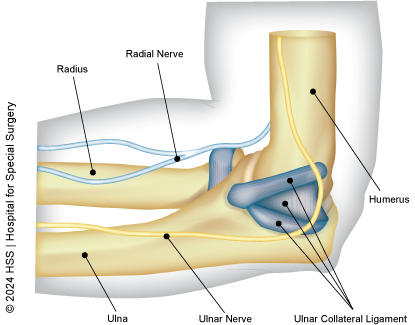

The ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) of the elbow is part of the complex of ligaments and tendons that attach and stabilize the bones of the lower and upper arm where they meet at the elbow joint. It is sometimes also referred to as the medial collateral ligament (MCL) of the elbow (not be confused with MCL of the knee.)

The UCL attaches the ulna bone (which, along with the radius, is one of the two bones of the lower arm) to the humerus bone of the upper arm. It connects these bones on the medial (inner) side of the arm.

View of the medial (inner) elbow showing the UCL

UCL injuries are also often called Tommy John injuries, named after the famed Major League Baseball player Tommy John who, in 1976, became the first person to return to play at the professional level after experiencing a complete tear of his ulnar collateral ligament.

What types of injuries affect the UCL?

Ulnar collateral ligament injuries can take the form of a UCL strain, sprain (partial tear) or complete tear, and these are classified into three basic grades:

- Grade I is when the ligament is strained but not torn.

- Grade II is a UCL sprain or partial tear.

- Grade III is a complete tear of the UCL.

How common are UCL injuries?

UCL injuries are relatively uncommon except among people involved in competitive sports. In athletes, especially those participating in frequent throwing activity – such as baseball pitchers, football quarterbacks, javelin throwers or lacrosse players – the forceful, repetitive motion of their sport can cause a ligament strain or tear, as well as other soft-tissue inflammation (swelling), cartilage injuries, or bone spurs at the elbow. It can also affect people in contact sports, although less often.

What causes a UCL injury?

UCL strains and tears often result from a gradual weakening process of the ligament, known as "attenuation." An explosive, forceful action, such as a fastball pitch can sometimes cause a traumatic injury of an otherwise healthy ulnar collateral ligament. Likewise, so can a traumatic injury such as an elbow dislocation or a collision in tackle sports such as football. Although less common, anyone who lands hard on their outstretched arm while attempting to break a fall, or who experiences a direct blow to the elbow can also injure their UCL.

Risk factors for UCL tears

Repetitive overhead throwing is the most common risk factor, especially among professional baseball pitchers or football quarterbacks. For pitchers, throwing too hard, too much, and/or with improper technique that puts excessive stress on the UCL, all increase the risk of injury. Other factors include:

- Muscle imbalances: Weakness or tightness of certain arm muscles can also contribute to UCL injuries by affecting the way in which you throw.

- Fatigue: Throwing when tired may increase your risk.

- Age: Ligaments become weaker and more susceptible to injury as we age.

How do you prevent a UCL injury?

Baseball pitchers, especially, should be conscious of throwing too hard or too often on a single day, especially those who are still learning or have not mastered the form for certain pitches. Younger pitchers who throw harder may stress the elbow more and be more prone to injury. For professional pitchers, throwing harder might be slightly riskier for needing surgery, but it likely won't affect their performance after the surgery.

In general, pitchers should work to improve any throwing mechanics they have not perfected, limit pitch count and throwing volume, and choose a wider variety of pitches to reduce repetitive stress in particular areas of the arm.

It was previously believed that a pitcher’s level of twist in the forearm at the time of foot contact had the greatest effect on risk of injury. Newer evidence suggests this may not be the case. Coaches and pitchers may be better off considering other aspects of throwing mechanics that might have a stronger influence on both injury risk and performance. Evidence also suggests that UCL injuries peak during March and April, suggesting that injury prevention measures are especially important during baseball spring training and the early season, when athletes return to increased play after a period of lower activity.

In addition, coaches, athletic trainers and athletes should be careful about sources of information regarding injury prevention. Seek professional guidance from physicians or rehabilitation specialists as well as websites from trusted organizations, such as hospitals or health agencies. Although many people turn to the internet, and YouTube in particular, to learn about UCL injury prevention, an HSS study researchers found that many videos posted on YouTube were not reliable, clear or well-explained and/or were missing important details that could be detrimental to athletes looking for advice.

How do I know if I tore a ligament in my elbow?

Most athletes will experience pain in the inside (medial) part of their elbow while throwing, along with loss of velocity and accuracy. This pain is almost always felt in the “layback” or “late cocking” phase of throwing. Some athletes feel a pop during a single pitch that immediately makes them unable to throw, while others feel gradually worsening pain and loss of velocity. Players will report an inability to throw as hard and as far as usual.

What are the symptoms of a UCL tear?

When the ulnar collateral ligament is torn, a person will still have a full range of motion in the elbow, as well as the ability to throw. However, they will not be able to exert significant force into a throw. In some cases, it may not even be immediately clear that the ligament has been torn. Some people report hearing a pop at the time of injury. Other symptoms can include pain, inflammation and/or bruising on the medial (inside) of the elbow and forearm, a weakened grasp, and pain or neuropathy (numbness) in the small fingers of the hand.

If you are experiencing pain on the inner side of your elbow, especially after throwing or other activities that involve repetitive elbow motion, it is important to see a doctor to get a diagnosis and discuss treatment options.

How is an UCL injury diagnosed?

A doctor will take your medical history and do a physical exam, likely including a valgus stress test, in which they will apply stress on the inside of your elbow while you keep it bent at 90 degrees. The test is considered positive if pain is reproduced or you have a feeling of instability. Tenderness over the insertion of the UCL is also noted. Usually, initial X-ray imaging is unremarkable, although presence of calcification over the ligament might be an indication of a chronic tear. If a tear is suspected, you will likely have an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) which best images the UCL and surrounding structures.

What kind of doctor treats UCL injuries?

If you suspect you have a torn UCL, you should consult a sports medicine physician or an orthopedist specializing in elbow injuries.

How is a UCL injury treated?

A minor UCL injury may be treated conservatively (without surgery). A partial or complete UCL tear will require surgery for an athlete to return to full activity. It is important to understand that not all athletes with UCL injuries should undergo surgery and a thorough conversation with the patient and family should be had prior to undergoing surgery.

A minor, Grade I UCL strain may be treated nonsurgically reducing activity that aggravates it, icing the elbow for 15 minutes several times a day, taking over-the-counter NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) such as ibuprofen, and doing physical therapy.

Physical therapy combined with platelet-rich plasma (PRP) treatment has been shown to offer promising results and a high rate of return-to-play in the competitive athlete. A UCL injury caused by an elbow dislocation should be treated in a different manner than that of an isolated UCL injury, as the elbow dislocation patient will have a larger zone of injury. Because of this, there is a great tendency for the injuries to heal with nonsurgical treatment.

What is the surgery for a UCL tear?

There are two basic types of UCL surgery: UCL reconstruction and UCL repair.

Surgical treatment: UCL reconstruction vs. UCL repair

Ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction, also known as Tommy John surgery, is a highly successful treatment for UCL tears and the primary surgical option for professional throwing athletes who wish to return to their sport. In this surgery, the UCL is replaced with a tendon graft taken from another part of the patient’s body (known as an "autograft").

A UCL repair, by contrast, involves the surgical reconnection of the native UCL where it has been torn. This option is usually reserved for partial tears and is sometimes more appropriate for a contact sport athlete, since they typically experience sudden tears in an otherwise healthy ligament, as opposed to one which has degenerated from continual use. When this is the case, a repair is more likely to be successful. HSS doctors and researchers are studying a new technique to repair torn UCLs using an internal bracing construct – a strong tape used to reinforce the ligament. There is evidence to suggest the new method is more successful than a repair alone, but more research is needed in this area. Advantages of repair using an internal bracing construct include faster return-to-play.

Throwing athletes, on the other hand, often experience a UCL tear resulting from overuse, which causes the ligament to degenerate over time. Repair of the original ligament is less optimal. Reconstruction using discrete tendon tissue is often the best option for any athlete to return to competitive play, even if their torn UCL is otherwise relatively healthy. In addition, complete, severe tears usually require reconstruction surgery.

Still, the choice between surgical reconstruction and repair can be based on many other factors. UCL repair is less invasive than reconstruction surgery, involves shorter recovery time and avoids the need to harness tendon tissue from another part of the body. However, it may not be suitable for complete tears or for older patients with weakened tissues, even those who are not planning to return to competitive play. With repair, there is also a higher risk of tearing the UCL again, versus UCL reconstruction.

What is the recovery time for UCL surgery?

There are variances depending on the severity of the tear, what level of activity the patient plans to return to and/or whether they have UCL reconstruction or UCL repair surgery. Complete recovery from Tommy John surgery involves extensive physical therapy and may take between 12 and 14 months for athletes to return to full competitive play. UCL repair recovery is typically faster, often taking between 6 and 12 months for an athlete to return to play.

Move Better Podcast on Tommy John surgery

Join HSS sports medicine surgeons David Altchek, James ("Beamer") Carr, and Josh Dines as they discuss UCL injuries, UCL repair and Tommy John Surgery.

Click or tap the "play" icon to listen on this page, the title to open it in Spotify, or visit the Move Better Podcast page to find this series on your preferred podcast platform.

Articles related to UCL injuries

Updated: 7/30/2024

Reviewed and updated by James B. Carr II, MD; Joshua S. Dines, MD and Stephen Fealy, MD

References

- Carr JB 2nd, Wilson L, Sullivan SW, Poeran J, Liu J, Memtsoudis SG, Nwachukwu BU. Seasonal and monthly trends in elbow ulnar collateral ligament injuries and surgeries: a national epidemiological study. JSES Rev Rep Tech. 2021 Oct 1;2(1):107-112. doi: 10.1016/j.xrrt.2021.08.013. PMID: 37588284; PMCID: PMC10426475.

- Kunze KN, Fury MS, Pareek A, Camp CL, Altchek DW, Dines JS. Biomechanical Characteristics of Ulnar Collateral Ligament Injuries Treated With and Without Augmentation: A Network Meta-analysis of Controlled Laboratory Studies. Am J Sports Med. 2024 Feb 2:3635465231188691. doi: 10.1177/03635465231188691. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 38304942.

- Manzi JE, Dowling B, Wang Z, Sudah SY, Quan T, Moran J, McElheny KL, Carr JB 2nd, Gulotta LV, Dines JS. Forearm Pronation at Foot Contact: A Biomechanical Motion-Capture Analysis in High School and Professional Pitchers. Orthop J Sports Med. 2023 Apr 19;11(4):23259671221145233. doi: 10.1177/23259671221145233. PMID: 37123995; PMCID: PMC10134138.

- Manzi J, Kew M, Zeitlin J, Sudah SY, Sandoval T, Kunze KN, Haeberle H, Ciccotti MC, Carr JB 2nd, Dines JS. Increased Pitch Velocity Is Associated With Throwing Arm Kinetics, Injury Risk, and Ulnar Collateral Ligament Reconstruction in Adolescent, Collegiate, and Professional Baseball Pitchers: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Arthroscopy. 2023 May;39(5):1330-1344. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2023.01.004. Epub 2023 Jan 14. PMID: 36649827.

- Moran J, Kammien A, Cheng R, Amaral JZ, Santos E, Modrak M, Kunze KN, Vaswani R, Jimenez AE, Gulotta LV, Dines JS, Altchek DW. Low Rates of Postoperative Complications and Revision Surgery After Primary Medial Elbow Ulnar Collateral Ligament Repair. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil. 2024 Jan 19;6(1):100828. doi: 10.1016/j.asmr.2023.100828. PMID: 38313860; PMCID: PMC10835117.

- Vaswani R, White A, Dines J. Medial Ulnar Collateral Ligament Injuries in Contact Athletes. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2022 Dec;15(6):474-482. doi: 10.1007/s12178-022-09785-0. Epub 2022 Aug 2. PMID: 35917095; PMCID: PMC9789220.

- Yu JS, Manzi JE, Apostolakos JM, Carr Ii JB, Dines JS. YouTube as a source of patient education information for elbow ulnar collateral ligament injuries: a quality control content analysis. Clin Shoulder Elb. 2022 Jun;25(2):145-153. doi: 10.5397/cise.2021.00717. Epub 2022 May 23. PMID: 35698784; PMCID: PMC9185119.