Cerebral Palsy: Surgery and Nonsurgical Orthopedic Treatments

Cerebral palsy (CP) is defined as any condition in the brain that causes a problem with the way an individual can use their muscles. Manifestations of CP vary considerably.

Because the brain is the control center for all of our human functions, sometimes the condition that results in cerebral palsy can cause other impairments in addition to affecting muscle movements, but frequently that is not the case.

Many individuals with cerebral palsy are limited only in their ability to move certain muscles, while having no cognitive or intellectual disability whatsoever.

- What are the treatment goals for children with CP?

- Treatments for ambulatory CP patients

- Motion analysis laboratory

- What surgeries are used?

- Treatments for non-ambulatory patients

- Advances in treatment: Improving function

What are the treatment goals for children with cerebral palsy?

Orthopedic surgeons, physiatrists and therapists who care for people with CP aim to optimize function in activities of daily living and improve overall quality of life. For individuals who can walk, maintenance and enhancement of that ability, and the independence it affords, is a primary goal. Treatment objectives for those who are not able to walk focus on preserving comfortable, balanced, and level sitting. This facilitates upright posture to observe surroundings, communicate with the world, and remain mobile in a wheelchair. (Find an HSS doctor who treats cerebral palsy.)

Treatments for ambulatory cerebral palsy patients (those able to walk)

Children birth to seven years

During the early years, from birth to about seven years of age, orthopedic issues are usually addressed without surgery, according to David M. Scher, MD, an associate attending orthopedic surgeon at Hospital for Special Surgery. “These measures include bracing and spasticity treatments, which can include injections of botulinum toxin (Botox) to relax overly tight muscles.”

When young children with spasticity are learning to walk, their muscles become tight, and their legs are unable to move into the right position at the right time. One of the most effective ways to decrease spasticity is with the use of focal tone management techniques. “Botox, phenol, or alcohol injections may be used to block some of the activity at the neuromuscular junction to ‘turn off’ some of the signal moving from nerve to muscle,” says Dara Jones, MD, assistant attending physiatrist. Other techniques such as nerve surgery (rhizotomy) and direct delivery of medication to the central nervous system (intrathecal baclofen) will also manage tone abnormalities such as spasticity and dystonia (involuntary and sustained muscle contractions that affect posture).

Children eight years and older

A child’s gait evolves throughout early childhood and, in children with CP who have had delays in their motor development, it eventually stabilizes by seven to eight years of age. Once a steady pattern of gait is established, clinicians often consider surgical interventions in addition to non-operative modalities as part of their treatment armamentarium.

Consideration of the individual’s entire lower extremity structure is paramount to the success of surgery. “Like medication, surgical procedures must be ‘dosed’ rather than given all at once to accommodate for growth, maturity, and balance,” explains Paulo Selber, MD, attending orthopedic surgeon. The decision-making at this point is quite complex and the team at Hospital for Special Surgery take a very thoughtful approach in order to make optimal, individualized treatment decisions. This includes utilization of three dimensional, instrumented gait analysis.

Pre-adolescence and beyond

During adolescence the natural history for children with CP who are able to walk is frequently to experience a decline in the appearance of the gait and in their endurance. The most common manifestation of this is bending down at the knees, called “crouch gait’. Sometimes crouch gait develops as a result of interventions a child has had earlier in life, but sometimes it is just the individuals natural history.

Motion analysis laboratory: A key to enhanced cerebral palsy treatment

Prior to surgical intervention at HSS, nearly all of our ambulatory individuals with cerebral palsy will undergo a gait analysis in the Hospital’s Leon Root, MD, Motion Analysis Laboratory. This sophisticated study used a technology called digital motion capture (similar to techniques used in creating computer generated imagery) to measure how the trunk, pelvis and all of the joints of the lower extremities are moving in all three planes of motion, while the individual is walking. The data is produced in graphical form, but for our clinicians trained in the interpretation of gait analysis, it is akin to watching someone walk from the front, the side and the top down all at the same time.

“This technology allows us to simultaneously analyze movement of the trunk, pelvis, hips, knees, ankles, and feet in three planes; how and when muscles are firing at different stages of the gait; and the forces on the joints during walking,” Dr. Selber explains. This allows the most accurate treatment decisions when planning surgical procedures and also guiding our patients about what to expect in the future. “By performing the studies before and after surgery, we refine our treatment approach and measure the success of surgical interventions.” motion analysis laboratory at Hospital for Special Surgery is the only clinical facility of its kind in the metropolitan New York City area and one of only 14 motion labs in the country accredited by the Commission on Motion Lab Accreditation.

What surgeries are used to treat cerebral palsy?

In the past, the main procedures performed for children with CP to optimize their gait were tendon lengthenings, such as lengthenings of the Achilles and hamstring tendons. These were relatively minor surgeries that were simple to perform and from which children recovered quickly. Typically, children would show improvements in their walking ability in the first several years after these surgeries, leading parents and doctors to believe that they had made the right decisions. However, longer follow-up, with the assistance of gait analysis to capture objective data, has helped us to understand that the early benefits from the treatments frequently dissipate due to the muscle weakness that results from these procedures. In fact, the individuals gait will sometimes decline more severely in the long term.

The recognition of these consequences and the knowledge gained through gait analysis has led to a newer treatment paradigm focused on optimizing the forces and individual can generate to enhance their gait. This is done by preserving muscle power (“dosing” any muscle procedures carefully) and by correcting the alignment of the bones using the principle of “lever arms” to make decisions. The lever arm principle is one that everyone is familiar with, even if one is not an engineer. If a person has ever sat on a teeter-totter, lifted a wheel barrel, opened a door or thrown a ball, then they have used a lever. By aligning the bones of the lower extremities in the optimal position, we can help individuals with CP generate the maximum forces possible (known as moments) when walking.

The types of surgeries done to help correct the levers and optimize “moments” in individuals with CP include osteotomies to rotate twisted femurs and tibias, foot surgery to make the feet more rigid and stable and knee surgeries to make the knees straighter in in order to correct crouch gait. “Surgeries can be especially effective in maximizing an individual’s mobility,” says Emily Dodwell, MD, associate attending orthopedic surgeon. “Not only do we use our motion analysis data to help with treatment decisions, but we also collect data after surgery to confirm that we’ve made improvements.”

Case study

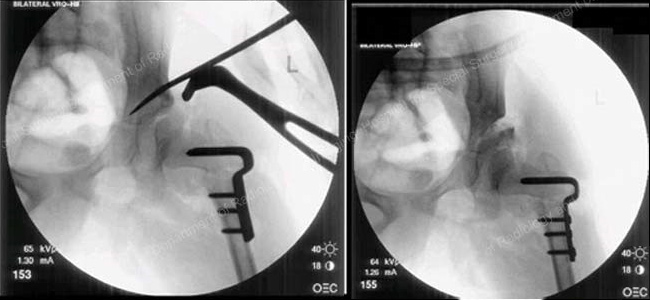

These X-rays show before-and-after surgery imaging of a seven-year-old girl with cerebral palsy who had a dislocated left hip and an abnormally aligned right hip.

Anteroposterior (front-to-back) X-ray showing dysplastic, dislocated left hip (shown at right) and coxa valga (abnormal alignment) of right hip (shown at left).

Intraoperative X-ray images obtained during a left varus rotational osteotomy (VRO) and a pelvic osteotomy.

Post-operative anteroposterior (front-to-back) X-ray obtained one year after left pelvic osteotomy and bilateral VRO, demonstrating that both hips are located.

Treatments for non-ambulatory patients with cerebral palsy

Caring for individuals with CP who are unable to walk is also a priority for our neuromuscular clinicians at HSS. Recent data has confirmed that optimal musculoskeletal care, such as hip surveillance and treatment, results in better long-term health outcomes and quality of life.

Non-ambulatory individuals with CP are at increased risk for hip dislocation, occurring in 60% to 70% of children who are unable to walk. Regular hip surveillance, using X-rays, is implemented to monitor the position of the hips for displacement over time.

Advances in treatment: Improving function in patients with cerebral palsy

Extensive research into the care of individuals with CP, done at HSS and at other centers around the world, has helped us dramatically improve the quality of life in individuals with CP. With dedicated and experienced clinicians working across multiple disciplines of musculoskeletal medicine and advanced tools, such as motion analysis, the cerebral palsy team at HSS have established themselves as one of the premier neuromuscular centers in the world.

Updated: 11/10/2022

Summary Prepared by Nancy NovickAuthors

Attending Orthopedic Surgeon, Hospital for Special Surgery

Professor, Clinical Orthopedic Surgery, Weill Cornell Medical College

Attending Orthopedic Surgeon, Hospital for Special Surgery

Professor of Clinical Orthopedic Surgery, Weill Cornell Medical College

Attending Physiatrist, Hospital for Special Surgery

Assistant Professor, Clinical Rehabilitation Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College

Attending Orthopedic Surgeon, Hospital for Special Surgery

Associate Professor of Orthopedic Surgery, Weill Cornell Medical College