Bilateral Optic Perineuritis Complicating Giant Cell Arteritis in a 76-Year-Old Woman

From Grand Rounds from HSS: Management of Complex Cases | Volume 13, Issue 3

Case Report

A 76-year-old woman was hospitalized after 8 days of diffuse headache and scalp tenderness that had initially responded to ibuprofen and acetaminophen. Two days prior to admission the headache worsened, and several painful nodules developed along the hairline. The patient noted blurred vision, and her internist advised hospital assessment given a concern for giant cell arteritis (GCA).

Her history included diabetes with neuropathy, hypothyroidism, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, adrenal nodules, and a pancreatic cyst. She had no history of alcohol or recreational drug use and no family history of autoimmune disease.

On presentation, temperature was 36.4°C, heart rate was 74 beats per minute, and blood pressure was 127/74 mmHg. Temporal arteries were prominent with strong, equal pulses; radial pulses were strong and equal. The left temporal region was mildly tender. There were 3 small, tender soft-tissue subcutaneous nodules on the left side of the forehead along the hairline. There was full range of motion in the shoulders and hips without pain. Laboratory studies revealed a normal complete blood count (CBC), normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and mildly elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) level at 1.64 mg/dL. Fundoscopic examination was normal.

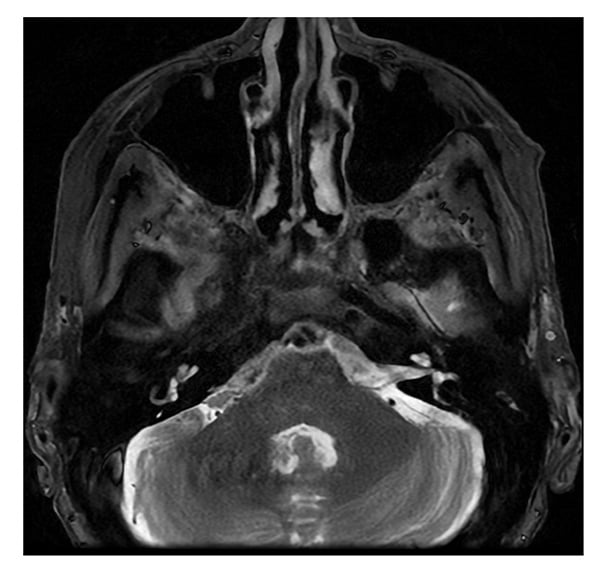

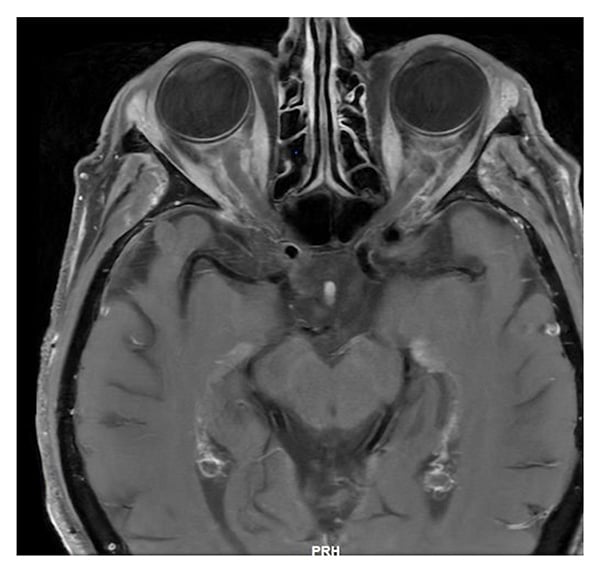

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the orbit and brain (Figures 1 and 2) revealed mild soft-tissue fullness surrounding the frontal branches of both superficial temporal arteries, suggestive of temporal arteritis. Marked superficial enhancement with fullness of the intraorbital segments of both optic nerves with surrounding fat reticulation was consistent with optic perineuritis. Serologic testing for tuberculosis, syphilis, sarcoidosis, immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4)-related disease, and monoclonal gammopathy was unremarkable.

Figure 1: MRI of the brain shows slight soft-tissue fullness surrounding the right greater than left frontal branches of the superficial temporal arteries.

Figure 2: MRI of the orbits: axial T1 post-contrast shows fullness of intraorbital ocular nerves, with surrounding fat reticulation.

She received methylprednisolone 500 mg for 3 days and underwent superficial temporal artery biopsy. Histopathology revealed lymphocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils in the adventitia, media, and focally thickened intima, plus disruption of the internal elastic lamina, consistent with GCA. She was started on subcutaneous tocilizumab 162 mg every 2 weeks and a prednisone taper. Four months later she developed recurrent temporal headaches, for which tocilizumab was increased to weekly and prednisone was increased from 30 to 60 mg.

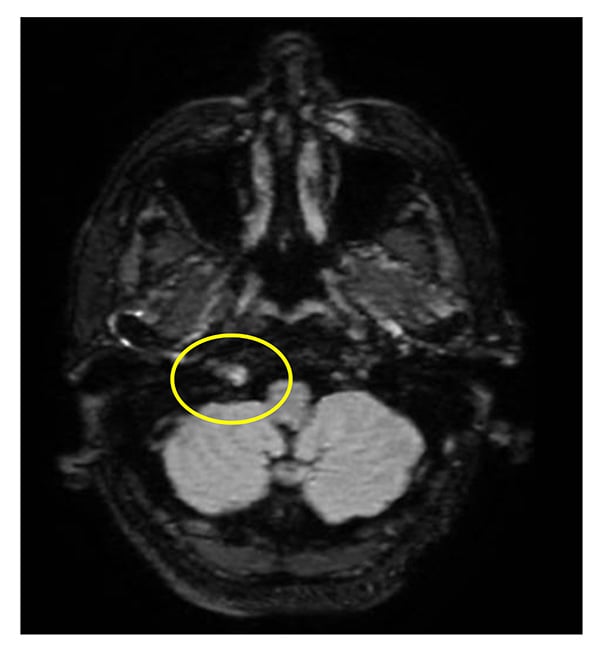

Three days later the patient developed dysarthria and was hospitalized. Neurologic examination found tongue deviation to the left, concerning for cranial nerve XII palsy. Laboratory evaluation revealed a neutrophilic leukocytosis with otherwise normal CBC, ESR, and CRP. MRI of the brain demonstrated hyperenhancement within the hypoglossal canal (Figure 3), which correlated with examination findings. Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed no evidence of malignancy. Lumbar puncture had normal cellularity and opening pressure and mildly elevated protein; tests including infectious workup, angiotensin-converting enzyme, oligoclonal bands, cytology, and flow cytometry were negative. Methotrexate 15 mg weekly with daily folic acid was added to prednisone and tocilizumab on discharge. Tongue deviation, dysarthria, and headaches resolved in the ensuing weeks and she continued to taper corticosteroids. Her course has been complicated by a deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism, for which she was treated with low-molecular-weight heparin.

Figure 3: MRI of the brain at the time of hospitalization: post-contrast T2 fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequence shows T2 enhancement within the right hypoglossal canal.

Discussion

Optic perineuritis is a rare orbital disorder characterized by inflammation of the optic nerve sheath. Most cases are idiopathic, although secondary etiologies have been described including infection, malignancy, and inflammation due to tuberculosis, syphilis, zoster, toxoplasmosis, lymphoma, GCA, Behçet’s disease, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA)-associated vasculitis, sarcoidosis, IgG4-related disease, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease, and inflammatory bowel disease [1]. Bilateral optic perineuritis should raise concern for a systemic process.

Clinically, optic perineuritis may present with acute or subacute vision loss, ocular pain with movement, diplopia, and ptosis. In contrast to optic neuritis, central vision is often spared [2]. Circumferential perineural enhancement is seen on MRI, and inflammatory infiltrates and thickening of the perineurium are found on histopathology. Biopsy of the optic nerve sheath is often deferred due to risks of procedural morbidity. Several case reports of optic perineuritis in association with GCA have been described [4-7], and a systematic review on orbital MRI findings in biopsy-proven ocular GCA found that optic perineuritis was present in 53% of 51 published cases [3]. High-dose corticosteroids and the management of underlying conditions are the mainstays of treatment.

This patient’s case is also notable for hypoglossal nerve involvement. Cranial neuropathy in association with large vessel vasculitis has been described in case reports [4-7]. Intracranial involvement by GCA is uncommon, due to the relative lack of internal elastic lamina in arteries beyond the dura. Treatment is directed at the systemic vasculitis.

References

- Saitakis G, Chwalisz BK. Optic perineuritis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2022;33(6):519–524. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000900.

- Gupta S, Sethi P, Duvesh R, Sethi HS, Naik M, Rai HK. Optic perineuritis. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2021;6(1):e000745. doi: 10.1136/bmjophth-2021-000745.

- Guggenberger KV, Pavlou A, Cao Q, et al. Orbital magnetic resonance imaging of giant cell arteritis with ocular manifestations: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Eur Radiol. 2023;33(11):7913–7922. doi: 10.1007/s00330-023-09770-2.

- Liou LM, Khor GT, Lan SH, Lai CL. Giant cell arteritis with multiple cranial nerve palsy and reversible proptosis: a case report. Headache. 2007;47(10):1451–1453. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00952.x.

- Fytili C, Bournia VK, Korkou C, Pentazos G, Kokkinos A. Multiple cranial nerve palsies in giant cell arteritis and response to cyclophosphamide: a case report and review of the literature. Rheumatol Int. 2015;35(4):773-6. doi: 10.1007/s00296-014-3126-8.

- Colquhoun M, Alegre Abarrategui J, Shahzad MI, Ellis B. Giant cell arteritis presenting with unilateral sixth nerve palsy. BMJ Case Rep. 2023;16(5):e253484. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2022-253484.

- Rigby WF, Fan CM, Mark EJ. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 39-2002—a 35-year-old man with headache, deviation of the tongue, and unusual radiographic abnormalities. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(25):2057–2065. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcpc020021.