Chronic Nonbacterial Osteomyelitis in an 11-Year-Old Girl

From Grand Rounds from HSS: Management of Complex Cases | Volume 13, Issue 3

Case Report

A healthy 11-year-old girl with no history of trauma or constitutional symptoms developed persistent right wrist pain. X-ray and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed an ovoid lucency of the left radius. These findings were concerning for osteomyelitis vs. neoplasm. Laboratory workup showed only mildly elevated inflammatory markers.

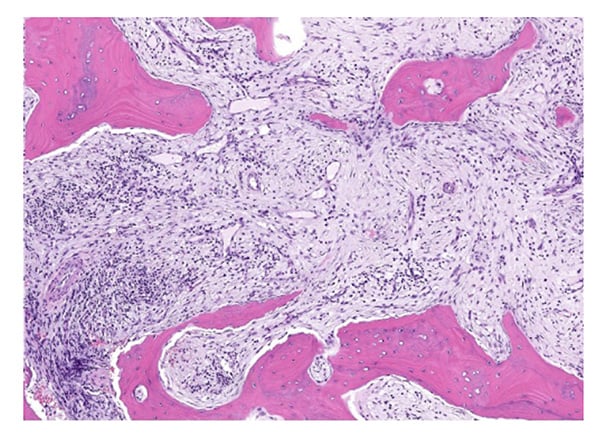

The patient underwent radial biopsy; results were consistent with viable lamellar bone with focal remodeling and patchy marrow fibrosis. She received cefazolin for presumed bacterial osteomyelitis, until bone cultures were found to be negative. A second biopsy revealed chronic inflammation with reactive bone (Fig. 1), and she was referred to rheumatology due to concern for chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis (CNO), also known as chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis.

Figure 1: Photomicrograph shows fibromyxoid tissue with patchy chronic inflammation filling the intertrabecular space between remodeling bony trabeculae (hematoxylin and eosin stain, 6× magnification). Courtesy Edward F. DiCarlo, MD.

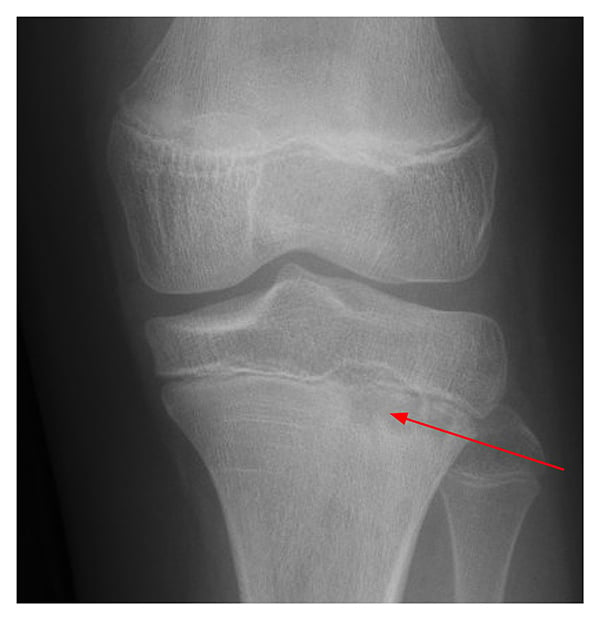

At her initial rheumatology visit, she also reported pain in the left knee and back. X-ray of the left knee revealed a metaphyseal lucency at the lateral tibia with mild surrounding sclerosis (Fig. 2). Whole-body MRI showed multiple metaphyseal regions of bone marrow edema lesions, with erosions of the left knee and right ankle consistent with CNO. Upper thoracic vertebral lesions were also found (Fig. 3).

Figure 2: Knee X-ray shows lateral tibia metaphyseal lucency with surrounding sclerosis.

Figure 3: Whole body MRI shows upper-thoracic vertebral lesions with marked bone marrow edema pattern.

Treatment with adalimumab and methotrexate was started due to spinal involvement and bony erosions. Inflammatory markers normalized, bone pain resolved, and at her most recent visit she was asymptomatic. She will undergo repeat whole body MRI in about 6 months after treatment initiation to re-assess bony lesions, which will help inform treatment decisions moving forward.

Discussion

CNO is an auto-inflammatory disorder that causes sterile osteomyelitis. CNO occurs most often in pre-pubertal children, with a mean age onset of 7 to 9 years [4]. Diagnosis of CNO is often delayed, and the disease is thought to be vastly underdiagnosed due to lack of awareness, insidious onset of pain, and often minimal findings on clinical exam [1].

The exact pathogenesis of CNO remains unknown, but imbalanced cytokine expression likely plays a significant role in the development of bone inflammation [4]. Although this was not the case in our patient, a genetic predisposition has been suggested by familial clusters of CNO and high prevalence rates of personal or family history of other inflammatory conditions, including inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, and inflammatory arthritis, in CNO patients [4].

The clinical presentation of CNO ranges from mild and self-limited unifocal disease to destructive and recurrent multifocal disease. CNO most commonly involves the metaphyseal regions of long bones. Whole body MRI is the pediatric gold standard for diagnosis and monitoring of CNO [3]. There are no pathognomonic laboratory findings or bone pathology patterns for CNO, but biopsy can be helpful in ruling out infection, fibrous dysplasia, or malignancy [4]. Biopsies of CNO lesions usually reveal areas of dense immune cells, bone lysis, fibrosis, or normal bone [2].

For children with CNO who have active spinal disease or whose symptoms are refractory to first-line non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, treatment options include methotrexate or sulfasalazine, TNF-α inhibitors with or without concomitant methotrexate, or bisphosphonates [5]. Given our patient’s active spinal lesions and multiple erosions, a regimen of adalimumab and methotrexate was recommended for aggressive control of bone inflammation.

The most common complications in CNO include vertebral compression fractures and bone deformities [4,5]. Though it is uncommon, pediatric providers should consider CNO when evaluating a child with chronic bone pain to prevent delay in diagnosis and resultant complications.

References

- Oliver M, Lee TC, Halpern-Felsher B, Murray E, Schwartz R, Zhao Y; CARRA SVARD CRMO/CNO workgroup. Disease burden and social impact of pediatric chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis from the patient and family perspective. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2018;16(1):78. doi: 10.1186/s12969-018-0294-1.

- Roderick MR, Shah R, Rogers V, Finn A, Ramanan AV. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO)—advancing the diagnosis. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2016;14(1):47. doi: 10.1186/s12969-016-0109-1.

- Andronikou S, Kraft JK, Offiah AC, et al. Whole-body MRI in the diagnosis of paediatric CNO/CRMO. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020;59(10):2671-2680. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keaa303.

- Zhao DY, McCann L, Hahn G, Hedrich CM. Chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis (CNO) and chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO). J Transl Autoimmun. 2021;4:100095. doi: 10.1016/j.jtauto.2021.100095.

- Zhao Y, Wu EY, Oliver MS, et al. Consensus treatment plans for chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis refractory to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and/or with active spinal lesions. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2018;70(8):1228-1237. doi: 10.1002/acr.23462.