Incident Rheumatoid Arthritis in a 64-Year-Old Woman with a Prosthetic Joint

From Grand Rounds from HSS: Management of Complex Cases | Volume 10, Issue 2

Case Report

A 64-year-old woman presented 16 months after bilateral total knee arthroplasty (TKA) with acute pain and swelling in her left knee that began during exercise and worsened; she also developed fatigue and malaise. X-rays demonstrated a well-fixed TKA in good position. Laboratory test results revealed an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 128 mm/hr and a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 5.8 mg/dL, mild anemia and thrombocytosis, and a normal white blood cell (WBC) count. Aspiration of the left knee yielded opaque fluid with an elevated WBC count of 17,457/μL (89% neutrophils) and a negative Gram stain without crystals.

Acute periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) was the presumed diagnosis, prompting urgent irrigation and debridement of the left knee with a liner exchange. Aspiration of her asymptomatic right knee was also performed, given the concern for a hematogenous infection, and revealed a WBC count of 6,700/μL (62% neutrophils). She began antibiotics (daptomycin and ceftriaxone) for an anticipated 6-week course, without significant improvement. Synovial fluid samples taken from both knees were cultured and found to be negative for bacteria, acid-fast bacilli, and fungi.

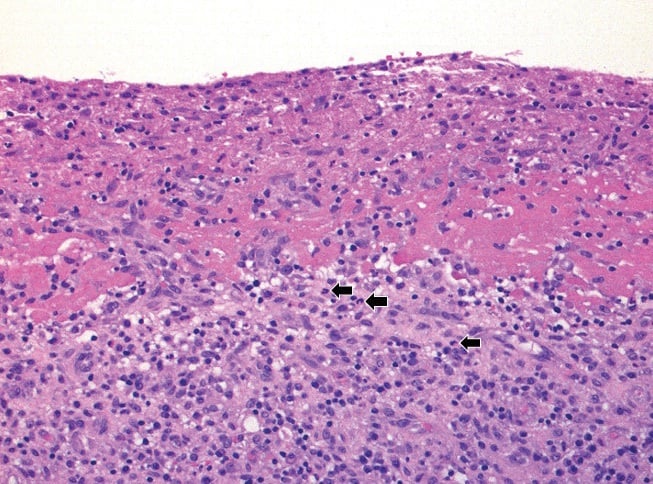

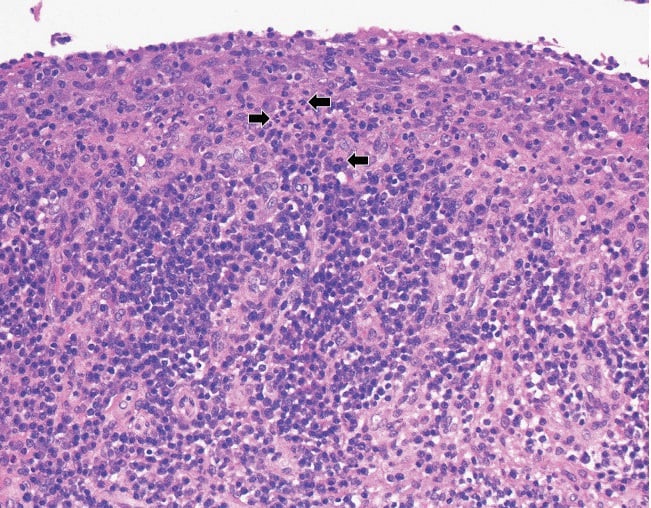

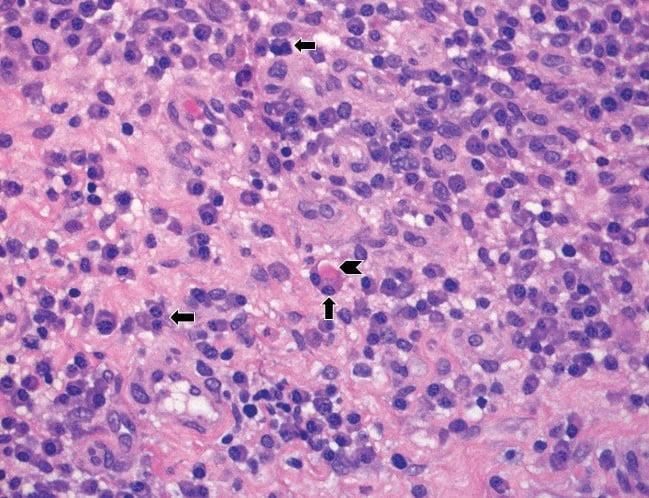

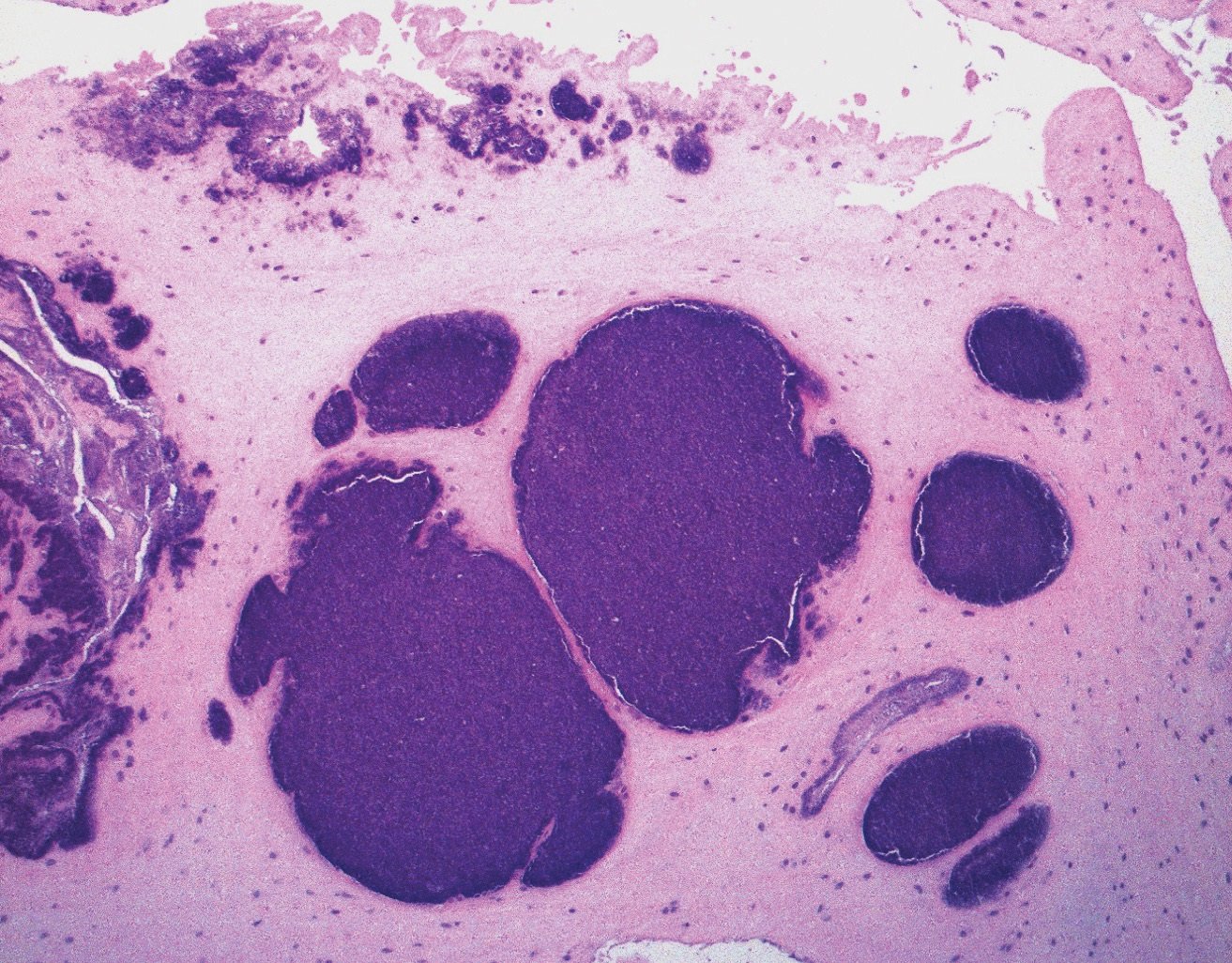

Histopathologic examination of the left knee tissue showed a proliferative and exudative synovitis with lymphoplasmacytic inflammation and scattered superficial neutrophils (Fig. 1A, 1B), as well as binucleated plasma cells and Russell bodies (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1A: Synovial tissue with marked lymphoplasmacytic inflammation, abundant superficial fibrinous exudate, and scattered neutrophils (arrows). Hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) stain, original magnification ×200.

Figure 1B: The synovial lining layer is well preserved in this area with marked lymphoplasmacytic inflammation and increased number of superficial neutrophils (arrows). H&E stain, original magnification ×200.

Figure 1C: High magnification of the lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with binucleated plasma cells (arrows) and a Russell Body (arrowhead). H&E stain, original magnification ×400.

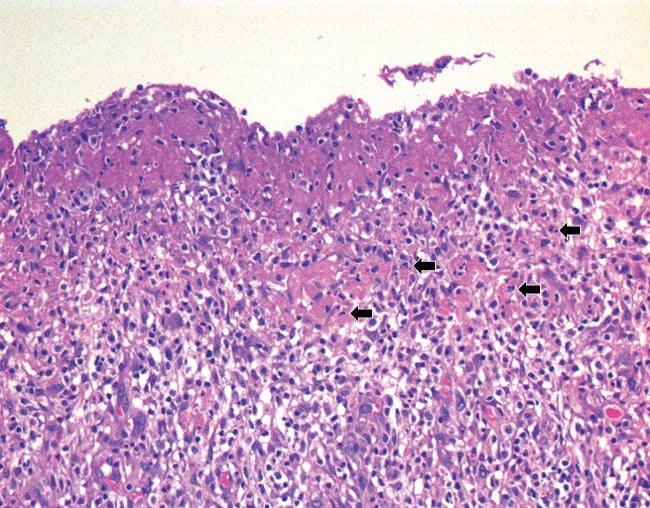

These findings were suggestive of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Focal granulation tissue with loss of the synovial lining layer and increased numbers of superficial neutrophils were suggestive but not diagnostic of infection (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1D: Granulation tissue with loss of the synovial lining layer and superficial fibrin; inflammatory infiltrate includes lymphocytes, plasma cells, and scattered neutrophils (arrows). H&E stain, original magnification ×200.

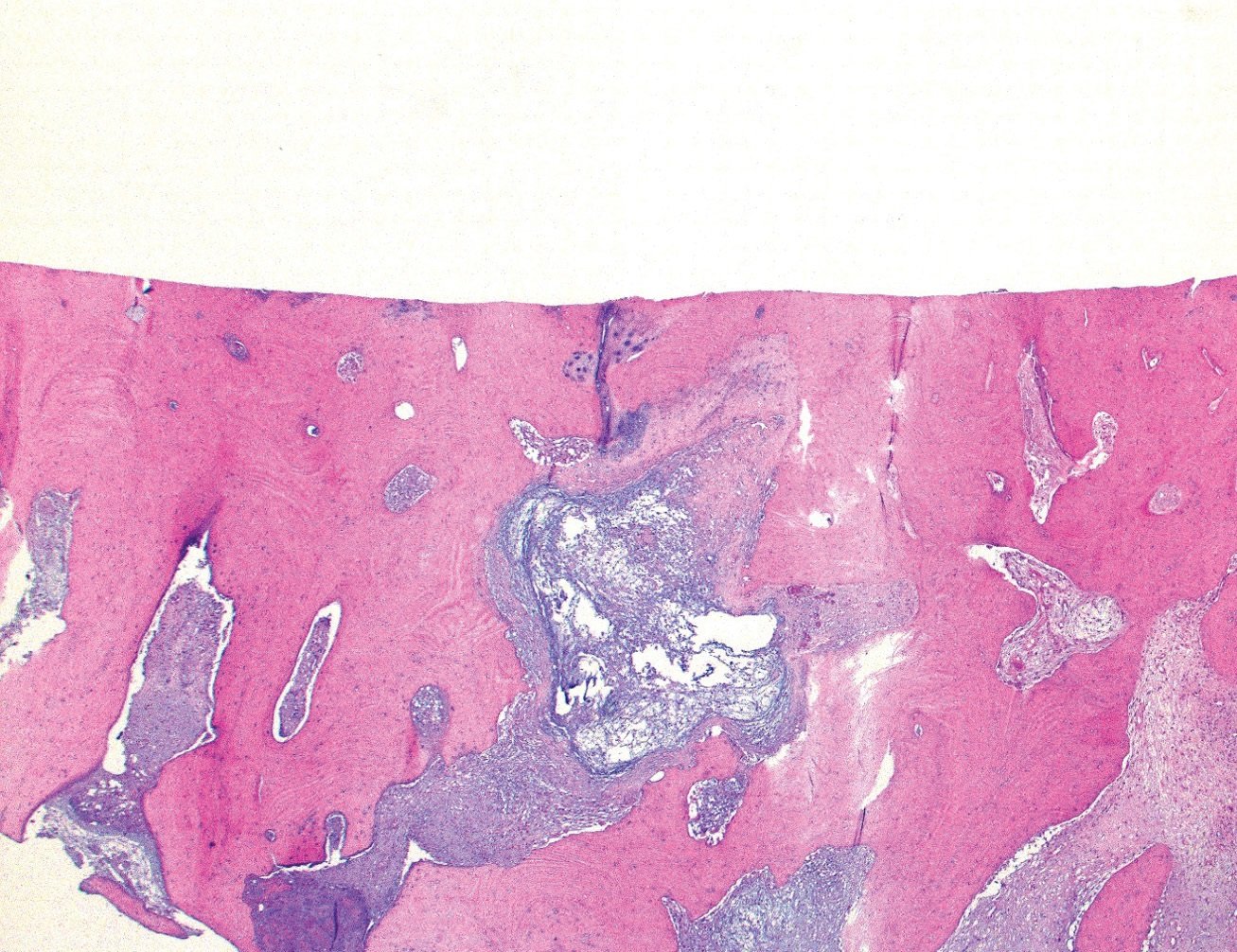

Review of the histopathology from the initial surgery confirmed degenerative joint disease without inflammatory features and moderate calcium pyrophosphate deposition (Fig. 2A, 2B).

Figure 2A: The articular surface demonstrates complete loss of the cartilage with moderate sclerosis of the exposed subarticular bone and a myxoid pseudocyst. H&E stain, original magnification ×25.

Figure 2B: The synovium and meniscus demonstrate calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition. H&E stain, original magnification ×100.

Additional serologic testing revealed a high-titer rheumatoid factor (RF) of 168.3 IU/mL and an anticyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibody level of more than 250 units, with persistent elevations in ESR and CRP. A rheumatology review of her history revealed no symptoms suggestive of inflammatory joint disease. However, based on serology and histopathology results and subsequent swelling of several metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints, RA was diagnosed. Antibiotics were stopped 4 weeks after surgery and methotrexate was begun. She has had a partial response to antirheumatic therapy, and her regimen is being adjusted to achieve better control.

Discussion

It is challenging to differentiate PJI from a flare of inflammatory arthritis, given the overlapping clinical and laboratory criteria for each diagnosis, especially when definitive microbiologic data are not available [1,2,3]. Furthermore, patients with rheumatoid arthritis are at increased risk for PJI and may have more frequent culture-negative infections [3]. Following any arthroplasty, elevated serum inflammatory markers and synovial fluid leukocyte levels are always concerning for PJI. Microbiology results can take time; because a delay in diagnosis may worsen outcomes, surgery should be performed promptly.

The patient’s initial monoarticular pain and swelling in a prosthetic joint was appropriately treated urgently as a presumed PJI. Histopathologic examination of the surgical specimen, showing polymorphonuclear leukocytes superimposed on the chronic inflammatory changes, was critical in pointing to the diagnosis of inflammatory arthritis. The RA diagnosis was corroborated by the patient’s lack of response to antibiotics, the subsequent serology results, and her clinical evolution to polyarthritis.

We know of no other reported cases of incident RA in a prosthetic joint. This case illustrates the ambiguity that often confronts rheumatologists. Tools to differentiate an inflammatory arthritis flare from PJI are needed to avoid the morbidity and expense associated with delay in making a definitive diagnosis and treating PJI. At HSS, research is under way to investigate serum and synovial biomarkers and next-generation microbial sequencing in arthroplasty patients with and without inflammatory arthritis to help diagnose PJI expeditiously in patients with inflammatory arthritis.

References

- Premkumar A, Morse K, Levack AE, Bostrom MP, Carli AV. Periprosthetic joint infection in patients with inflammatory joint disease: prevention and diagnosis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2018;20(11):68.

- Mirza SZ, Richardson SS, Kahlenberg CA, et al. Diagnosing prosthetic joint infections in patients with inflammatory arthritis: a systematic literature review. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34(5):10321036.e2.

- Goodman S, Kapadia M, Miller A, et al. Clinical features of prosthetic joint infections in patients with rheumatic diseases vs osteoarthritis [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019; 71 (suppl 10). Presented at: 2019 ACR/ARP Annual Meeting; November 8-13, 2019; Atlanta, GA.