Microneurolysis to Treat Anterior Interosseous Nerve Syndrome Resulting from Parsonage–Turner Syndrome

From Grand Rounds from HSS: Management of Complex Cases | Volume 9, Issue 1

Case Report

A 52-year-old right-handed woman presented with 12 months of paralysis of her right thumb. Her symptoms started 1 week following an episode of septic shock while hospitalized for an acute small bowel obstruction. She did not recall antecedent arm or forearm pain, although she found it difficult to recall specific symptoms she endured during her severe illness.

Physical examination showed proximal forearm atrophy, with a positive Kiloh–Nevin sign [1]. British Medical Research Council (BMRC) strength grading [2] was notable for M0 strength in the flexor pollicis longus (FPL), M4 strength in the index finger flexor digitorum profundus (FDP), and M5 strength in the long finger FDP. The patient otherwise had full strength of all right upper extremity muscles and no sensory deficits.

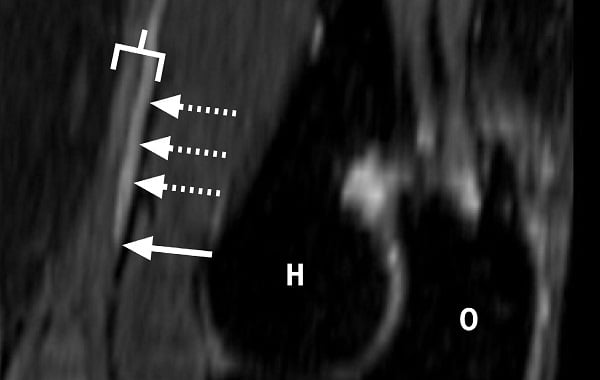

Electrodiagnostic testing (EDX) was notable for moderate to severe spontaneous activity, with no voluntary motor activity in the FPL or pronator quadratus (PQ), diagnostic of complete denervation. The patient also had incomplete denervation of the index FDP, marked by mild abnormal spontaneous activity, nascent voluntary motor unit action potential, and decreased recruitment pattern. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the right brachial plexus demonstrated signal hyperintensity in 2 posteriorly positioned fascicles of the median nerve, approximately 7 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle. These fascicles showed focal caliber changes suggestive of fascicular constrictions at the level of the medial epicondyle and within 2 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle [4] (Fig. 1). Right forearm MRI demonstrated no extrinsic compression of the median nerve. Right forearm ultrasound demonstrated no thickening or contour lobulation of the anterior interosseous nerve (AIN), with some denervation effect seen in the PQ and FPL.

Figure 1: Curved, multiplanar reformatted sagittal projection T2-weighted fat suppressed image demonstrates abnormal signal hyperintensity of a posteriorly positioned fascicular bundle (dashed arrows) of the median nerve proper (bracket) within the distal arm. Note the sharp tapering of the fascicle as it approaches the elbow joint, compatible with an intrinsic constriction (solid arrow). Distal humerus (H), olecranon (O).

Based on these findings and the lack of improvement in the patient’s symptoms, she was diagnosed with AIN syndrome (AINS) [3]. Operative and non-operative treatments were discussed, and the patient elected to undergo microneurolysis of the median nerve.

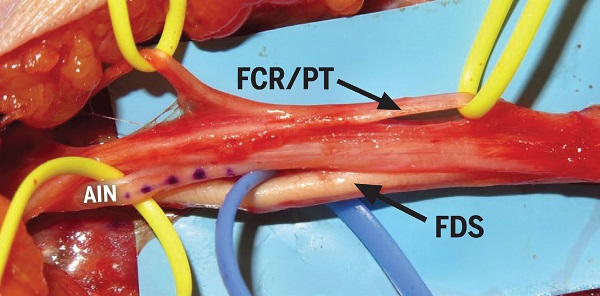

A medial supracondylar incision was made from the medial mid-arm to a point just distal and anterior to the medial epicondyle. The median nerve was identified and determined to have an excellent perineural vascular pattern. Under loupe magnification (3.5× power), the nerve was rotated to identify the posterior fascicular groups, which appeared pale and swollen. The epineurium was opened, and posterior fascicles were separated by intraneural dissection under the operative microscope (10× power). The flexor carpi radialis and pronator teres fascicles were identified and confirmed by handheld electrical stimulation at 0.5 mA. The dissection was continued proximally in the parent nerve to identify and stimulate additional fascicular groups. The posterior fascicles stimulated the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) strongly, but the posteromedial fascicular group, which did not respond to stimulation, was determined to represent the AIN fascicular group (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Anterior and posterior fascicles of the median nerve following intra-neural dissection. Flexor carpi radialis (FCR) and pronator teres (PT) fascicles stimulated strongly and are held by yellow vessel loops on the top portion of the image. The posterior fascicle to the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) stimulated strongly and is held by blue vessel loops at the bottom of the image. The posteromedial fascicles (dotted) did not stimulate and were determined to represent AIN fascicles.

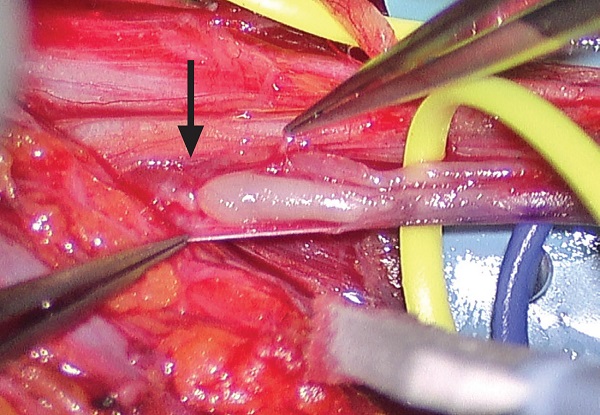

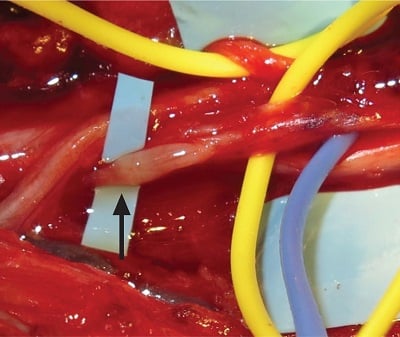

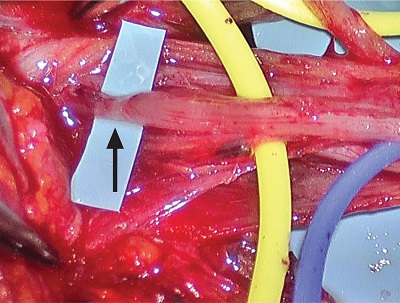

Each fascicular group was traced proximally and distally, and a meticulous search for fascicular constrictions was performed. The FPL fascicle of the anterior interosseous nerve fascicular group had an acute constriction at the level of the medial epicondyle. Under the microscope, the constriction was noted to have the appearance of a “nerve torsion” [4] (Fig. 3). Perineurolysis was performed, which revealed spiral perineural fibrous bundles surrounding and constricting the nerve fascicle, which was swollen proximal and distal to the fascicular constrictions in an “hourglass” configuration (Fig. 4). After division of the perineural bands, the fascicle was identified to be translucent; within minutes it swelled to near normal caliber with a healthier appearance (Fig. 5). There was no torsion of the nerve or the fascicles themselves. The wound was closed, and the patient was allowed gentle range of motion of the elbow, progressing to activity as tolerated over the next several weeks.

Figure 3: Anterior interosseous nerve fascicle with pre-stenotic dilatation and spiral bands (black arrow).

Figure 4: Perineurolysis of the AIN branch revealing an hourglass constriction (black arrow).

Figure 5: AIN fascicle 30 minutes after microneurolysis, showing increased vasculature and translucency at the site of the prior hourglass constriction (black arrow).

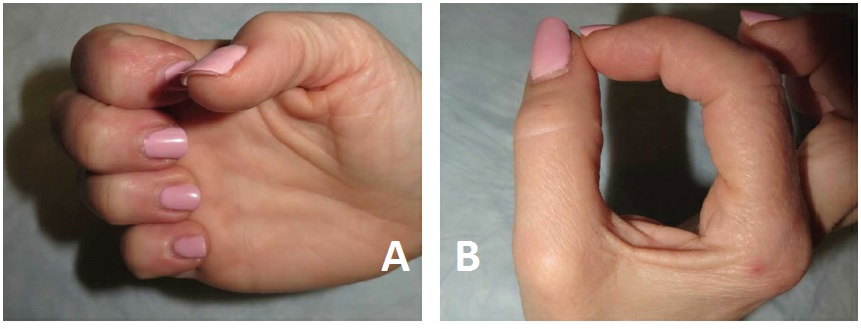

Eleven months after micro–internal neurolysis, the patient had M4 strength in the FPL, with 50° active range of motion, and M4+ strength in the index FDP, with full range of motion (Fig. 6). She had M5 strength in pronation. EDX demonstrated mild abnormal spontaneous activity and decreased recruitment in the FPL and the PQ, suggesting axonal regeneration and near complete motor unit recovery.

Figure 6: The patient, 1 year postoperatively, showed improved ability to flex at the thumb interphalangeal joint and index finger distal interphalangeal joint.

Discussion

This case shows the utility of microneurolysis in a patient with characteristic clinical, electrodiagnostic, and imaging findings of AINS, an idiopathic axonopathy of the median nerve that causes an acute motor palsy of the muscles innervated by the AIN. AINS is a subtype of neuralgic amyotrophy, also called Parsonage–Turner syndrome (PTS) [5]. Although AINS was conventionally considered an idiopathic forearm neuropathy, it is now recognized as a disorder of the median nerve, characterized by fascicular constrictions at or proximal to the elbow [3].

Furthermore, this case highlights the importance of a multimodal diagnostic strategy involving EDX and targeted, nerve-specific imaging to identify the fascicular constrictions characteristic of AINS and PTS [3]. Previously, MRI and ultrasound served a secondary role in diagnosing PTS by showing muscle denervation and evaluating for causes of external compression in the forearm. As in this case, high-resolution diagnostic MRI can pinpoint localization of anterior interosseous fascicles of the median nerve and assist the surgeon in localizing and decompressing fascicular constrictions.

References

- Kiloh L, Nevin S. Isolated neuritis of the anterior interosseous nerve. Br Med J. 1952; 1(4763): 850–851.

- Medical Research Council. Aids to the investigation of the peripheral nervous system. London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office; 1943.

- Sneag D, Aranyi Z, Zusstone E, et al. Fascicular constrictions above elbow typify anterior interosseous nerve syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 2019:1–10. doi: 10.1002/mus.26768.

- Sneag D, Saltzman E, Meister D, Feinberg J, Lee S, Wolfe S. MRI bullseye sign: an indicator of peripheral nerve constriction in Parsonage–Turner syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 2017;56(1):99–106.

- Strohl AB, Zelouf DS. Ulnar tunnel syndrome, radial tunnel syndrome, anterior interosseous nerve syndrome, and pronator syndrome. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2017;25(1):e1–e10.