Relapsing Lupus Nephritis and Cutaneous Vasculitis: A Race to Contain B Cells

From Grand Rounds from HSS: Management of Complex Cases | Volume 9, Issue 2

Case Report

A 45-year-old woman with a history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) since 2006 came to HSS in 2014 for continued management of SLE. Disease manifestations included arthritis, alopecia, Raynaud’s phenomenon, lymphadenopathy, pericarditis, and mononeuritis multiplex. She also had a recurrent erythematous, tender rash on her lower legs; a biopsy revealed leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) with deposits of immunoglobulin M (IgM) and to a lesser extent IgA and C4d within the microvasculature, consistent with an SLE-associated immune complex-mediated vasculitis. Positive serologies included antinuclear antibody, anti-Smith, anti-Ro, anti-La, and anti-RNP antibodies; low levels of serum complement component 3 and 4 (C3 and C4) were found. Results were negative for anti-dsDNA antibodies, antiphospholipid antibodies, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), rheumatoid factor, and cryoglobulins. She was treated with corticosteroids (CS), hydroxychloroquine, azathioprine, tacrolimus, and belimumab. Severe flares of the disease required high-dose CS therapy.

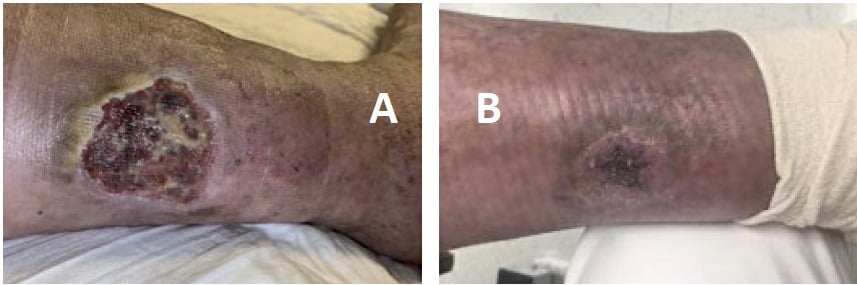

Despite this treatment, she developed progressive disease in 2018, with palpable purpura extending to her proximal legs, arms, and trunk (Fig. 1). In the following months, she developed new nephrotic-range proteinuria and microscopic hematuria. A kidney biopsy showed diffuse class IV glomerulonephritis with prominent intra-capillary hyaline “thrombi” and IgM and IgG mesangial and subendothelial deposits. She received pulse-dose and high-dose oral CS and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) 3000 mg/day, with partial improvement in kidney function and proteinuria.

Figure 1: Representative vasculitic lesions on the patient’s trunk.

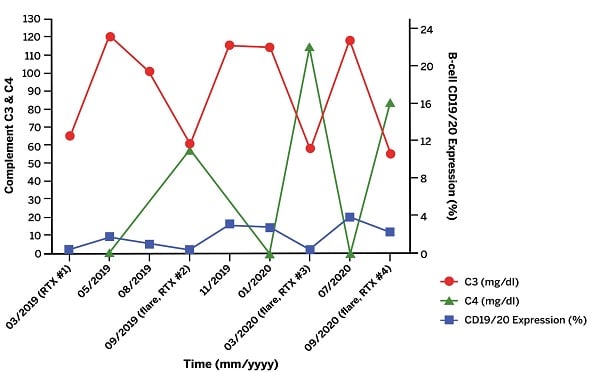

However, the rash remained active, causing severe pain and ulceration (Fig. 2A), despite treatment with MMF, CS, diuretics, and wound care. Two doses of rituximab 1000 mg separated by 2 weeks were added to her regimen, resulting in marked improvement in skin lesions and proteinuria and successful tapering of CS. Unfortunately, the nephritis and cutaneous vasculitis flared again 5 months later, coinciding with B-cell repletion and a decrease in C3/C4 levels, just before her next scheduled dose of rituximab. This pattern continued (Fig. 3), despite addition of weekly belimumab. The refractory left leg skin ulcer eventually healed (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2: Ulcerated lesion on lower extremity (A) that resolved after initiation of rituximab, belimumab, and local wound care (B).

Figure 3: Laboratory data trend of complement levels and B-cell CD19/CD20 expression as a function of time. Time points marked by “flare” signify a flare of patient’s rash and nephritis. “RTX” indicates rituximab was administered at this time point.

Discussion

Vasculitis occurs in 11 to 20% of SLE patients, most frequently as a small vessel LCV manifesting as cutaneous lesions [1]. The development of cutaneous vasculitis in patients with SLE has been demonstraed to correlate with increased SLE activity overall, therefore warranting additional therapy for disease control [1].

This case highlights the role of B-cell targeted therapies for both cutaneous vasculitis in SLE and lupus nephritis. The presence of immune complexes in the skin and kidney biopsies, as well as the profound serum C3/C4 level drop coinciding with the vasculitic and nephritic flares, suggested a dominant role of the autoimmune B-cell pathway in causing these manifestations. The therapeutic approach thus shifted to B-cell targeted agents with complementary mechanisms of action: an anti-CD20 antibody, rituximab, and an antibody against soluble B-lymphocyte stimulator (BLyS), belimumab [2]. The patient’s condition improved with this combination, but the disease predictably flared when CD19/CD20 B-cell subsets repopulated just prior to the next dose of rituximab. Efforts to preempt flares now involve accelerated dosing of rituximab to every 4 months.

We are unsure why this patient’s disease remained refractory. Transient and/or incomplete B-cell depletion is thought to contribute to resistant disease by selecting for potentially more pathogenic B-cell clones [2]. Additionally, while rituximab results in near complete depletion of circulating B-cells, those in tissues remain relatively unaffected [2]. Thus, future therapeutic considerations for refractory cases may include achieving a more durable B-cell depletion in peripheral blood and tissue with alternative anti-CD20 antibodies, such as obinutuzumab, which is currently under investigation for use in patients with lupus nephritis [3]. Other therapies for refractory SLE under investigation include Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors and plasma cell-targeted agents such as proteasome inhibitors [4, 5].

References

- Ramos-Casals M, Nardi N, Lagrutta M, et al. Vasculitis in systemic lupus erythematosus: prevalence and clinical characteristics in 670 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2006;85(2):95-104.

- Teng YKO, Bruce IN, Diamond B, et al. Phase III, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 104-week study of subcutaneous belimumab administered in combination with rituximab in adults with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): BLISS-BELIEVE study protocol. BMJ Open. 2019;9(3):e025687

- Furie R, Aroca G, Alvarez A, et al. A phase II randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of obinutuzumab or placebo in combination with mycophenolate mofetil in patients with active class III or IV lupus nephritis [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10).

- Alexander T, Sarfert R, Klotsche J, et al. The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib depletes plasma cells and ameliorates clinical manifestations of refractory systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(7):1474-1478

- Isenberg D, Furie R, Jones N, et al. Efficacy, safety, and pharmacodynamic effects of the Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor, fenebrutinib (GDC-0853), in moderate to severe systemic lupus erythematosus: results of a phase 2 randomized controlled trial [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10).