Addressing Significant Glenoid Deformity in a Younger Patient with Glenohumeral Osteoarthritis

From Grand Rounds from HSS: Management of Complex Cases | Volume 10, Issue 1

Case Report

A 56-year-old man presented with several years of right shoulder pain after a failed trial of conservative therapy. An energetic man who wanted to return to his prior active lifestyle, he had undergone left shoulder hemiarthroplasty but continued to have functional limitations on that side. He hoped for better results on the right side.

On examination, range of motion in the right shoulder was 140° of forward elevation, 20° of external rotation, and internal rotation to his lumbar spine. Significant crepitus was noted. His rotator cuff strength demonstrated 5/5 supraspinatus, 5/5 external rotation, and 5/5 subscapularis.

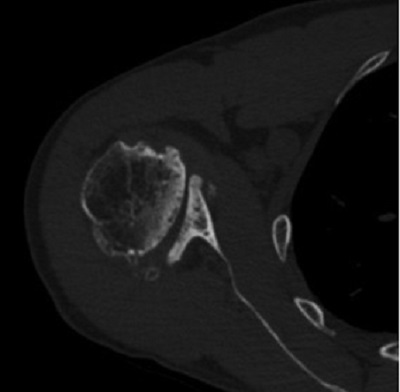

Radiographs of the right shoulder showed end-stage glenohumeral osteoarthritis with significant glenoid retroversion (B3 Walch classification) [1] and posterior humeral head subluxation (Fig. 1). A computed tomography (CT) scan to assist with preoperative planning showed excessive glenoid wear, with 25° of retroversion (Fig. 2).

Figure 1: Anteroposterior (AP) (left) and axillary (right) radiographs of the right shoulder

demonstrate glenohumeral osteoarthritis with a B3 glenoid deformity.

Figure 2: Axial CT image demonstrates 25° of glenoid retroversion.

The patient underwent an anatomic total shoulder replacement using a convertible glenoid baseplate with bone grafting to correct significant retroversion. A standard deltopectoral approach with the patient in the beach chair position was used. A lesser tuberosity osteotomy was performed and the humeral head was cut in 30° of retroversion. The cut humeral head was taken to the back table to be used for autograft on the back of the glenoid baseplate.

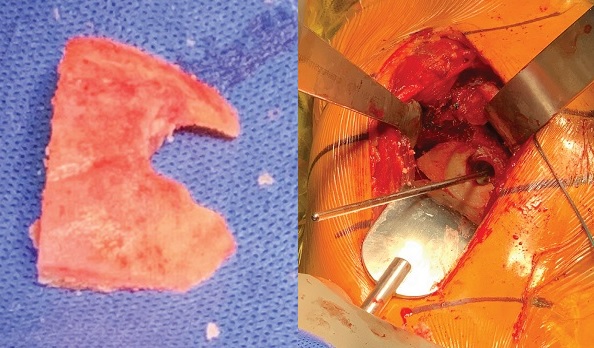

Exposure of the glenoid was notable for significant retroversion, consistent with preoperative imaging. A guide pin was placed down the glenoid vault in the appropriate orientation. Reaming was then performed so that the anterior 50% of the baseplate was flush with native bone. The cut humeral head was reamed with the central screw boss and then cut in half and shaped to fit the posterior aspect of the glenoid (Fig. 3). The humeral head autograft was placed on the posterior glenoid and the baseplate impacted into place and secured with the central compression screw. Two locking screws were placed superiorly and inferiorly, providing excellent fixation. The polyethylene liner was impacted into place, followed by finishing preparation of the humerus and repair of the lesser tuberosity osteotomy.

Figure 3: Humeral head autograft (left) and placement on the posterior glenoid (right).

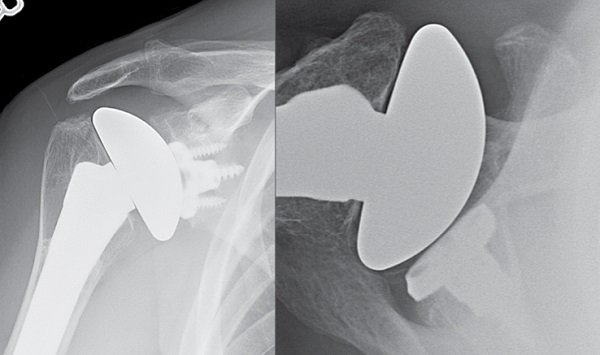

The patient had an excellent recovery. After immobilization in a sling for 4 weeks, he began progressive physical therapy to regain motion and strength. At the 4-year follow-up examination, his right shoulder demonstrated 170° of forward elevation, 60° of external rotation, and internal rotation to T8. His rotator cuff strength was 5/5. Radiographs showed that the right humeral head was well centered, the glenoid version was neutral, and the bone graft had incorporated on the posterior glenoid (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: AP (left) and axillary (right) radiographs at 4-year follow-up demonstrate right anatomic shoulder replacement with metal backed convertible glenoid, restoration of neutral glenoid version, and incorporation of the bone graft.

Discussion

Significant glenoid deformity presents a challenge to the surgeon managing a patient with glenohumeral osteoarthritis with an anatomic shoulder arthroplasty. Depending on the degree of deformity, treatment may include eccentric reaming using a posteriorly augmented polyethylene glenoid component or bone grafting using a convertible glenoid baseplate.

Given the degree of retroversion in this case, eccentric reaming would have sacrificed too much bone for glenoid fixation, and a standard posterior augment would not have corrected the glenoid version. Historically, anatomic shoulder replacement with a metal-backed glenoid had poor survivorship [2], but the advent of locking screws and improved polyethylene and porous materials have renewed interest in its use. In this case, a convertible glenoid had the benefits of allowing bone grafting of the posterior glenoid to correct the retroversion, while allowing secure fixation of the glenoid component. (Few studies have examined long-term outcomes of this procedure.) Younger patients undergoing anatomic shoulder replacement may require a revision in their lifetime [3, 4]; a convertible glenoid may allow for easier transition to a reverse shoulder replacement, if that is required.

Posted: 8/2/2021

Authors

Ryan C. Rauck, MD

Orthopaedic Surgery Clinical Fellow

Hospital for Special Surgery

Chief, Shoulder and Elbow Division, Sports Medicine Institute, Hospital for Special Surgery

Attending Orthopedic Surgeon, Hospital for Special Surgery

REFERENCES:

- Walch G, Badet R, Boulahia A, Khoury A. Morphologic study of the glenoid in primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14(6):756–760.

- Gauci MO, Bonnevialle N, Moineau G, Baba M, Walch G, Boileau P. Anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty in young patients with osteoarthritis: all-polyethylene versus metal-backed glenoid. Bone Joint J. 2018;100-B(4):485–492.

- Sperling JW, Cofield RH, Rowland CM. Neer hemiarthroplasty and Neer total shoulder arthroplasty in patients fifty years old or less. Long-term results. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(4):464–473.

- Denard PJ, Raiss P, Sowa B, Walch G. Mid- to long-term follow-up of total shoulder arthroplasty using a keeled glenoid in young adults with primary glenohumeral arthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(7):894–900.