Pelvic Fracture / Acetabular Fracture

Breaks in the pelvis or acetabulum of the hip joint are among the most serious injuries treated by orthopedic surgeons. Often the result of a traumatic incident such as a motor vehicle accident or a bad fall, pelvic and acetabular fractures require rapid and precise treatment and, in some cases, one or more surgical procedures. People of all ages are vulnerable to these injuries. In addition, some elderly patients with fragile bones due to osteoporosis develop pelvic fractures and fractures of the acetabulum with a lower impact fall.

- Overview of fractured pelvis

- Treatment goals

- Nonsurgical treatment

- Surgical treatment

- What are the complications of surgery for a broken pelvis?

- The Orthopedic Trauma Service at HSS

- Frequently asked questions and answers

Overview of a fractured pelvis

The complex nature of these fractures can be better understood by looking at the anatomy that is involved. The pelvis is made up of several bones (ileum, ischium and pubic bones) which create a bony ring, meeting at the pubic symphysis in the front and the sacrum (a bone situated at the lower end of the spine) in the back. Together with a number of ligaments and muscles, the bones of the pelvis support the weight of the upper body and rest on the hip joints. The pelvis protects abdominal organs including the intestines and the bladder, as well as major nerves and blood vessels. Pelvic fractures may occur at any location on the bones depending on the nature of the accident and the areas of impact.

Radiograph of a normal pelvis

Radiograph of the pelvis demonstrating a fracture of the pubic bone

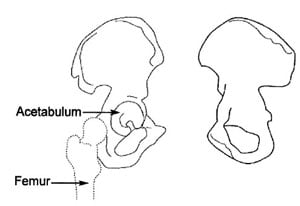

The acetabulum refers to the part of the pelvis that meets the upper end of the thigh bone (the femoral head to form the hip joint. In a healthy hip, these two bones fit together like a ball and cup, in which the ball rotates freely in the cup. Cartilage lines the bones where they meet at the joint and there is little friction between the surfaces during movement.

Anatomical illustration of the acetabulum

Most people use the term "broken hip" to refer to a fracture of the ball side of the joint, that is, a break in one of two sections of the femur:

- femoral head (the "ball" at the very tip of the upper femur)

- femoral neck (a broad section of the upper femur just below the femoral head)

In this section, we are speaking specifically of a fracture of the cup or acetabulum. Fractures of the acetabulum are harder to treat because access to this bone is more difficult, and because of the acetabulum's proximity to the major blood vessels to the legs, the sciatic nerve (the major nerve that arises from the lower spine and provides sensation and movement to the leg and foot), the intestines, the ureter and the bladder. Unlike a hip fracture, which can be treated relatively easily, to repair an acetabular fracture, the orthopedic surgeon, must, in essence, fix the broken bones from the inside out.

In fractures of this type, the femoral head is often driven through the acetabulum because of the impact of the fall or accident. If the femoral head ends up outside the acetabulum, this is known as a dislocation of the hip joint. Some patients have both a fracture and a dislocation.

Radiograph of the left hip demonstrating a posterior dislocation of the hip with an associated

Posterior Wall type fracture of the acetabulum

Unfortunately, patients with fractures of the pelvis and/or acetabulum, almost always also experience serious injury to surrounding soft tissue (skin and muscles) and neurovascular structures (nerves, arteries and veins). In addition, especially in the case of pelvic fractures, adjacent organs can be seriously injured. With both types of fracture, there is significant bleeding and risk of nerve damage.

In patients with multiple injuries, treatment begins with the trauma team at the scene, and then subsequently in the emergency room – a team of general surgeons, anesthesiologists and nurses – who work together to control bleeding, address damage to the head and chest, and other organs that may have been affected, such as the bladder and intestines, and to stabilize broken bones. During this early resuscitation phase of treatment, the orthopedic surgeon may need to stabilize the fracture by using an external frame to temporarily hold the bones in proper alignment while other problems are treated. This is called temporary external fixation. Surgeons construct these frames using steel pins that are inserted into the bone and joined together by clamps and rods and can do so very rapidly.

Radiograph of the pelvis demonstrating application of a pelvic external fixator.

Once the patient is stabilized – bleeding has stopped and other life-threatening injuries have been addressed – the fractures can be treated definitively. Successful treatment for both of these types of fractures requires the skills of an interdisciplinary team, with orthopedic surgeons working closely with the trauma team (general surgeons), the anesthesiologists and nurses. Following surgery, rehabilitation specialists play a key role in recovery.

Because of the complex nature of these fractures and because many orthopedic surgeons do not regularly treat them, patients who initially go to a community hospital for emergency attention are often transferred to an institution that specializes in such injuries.

Treatment goals

As with any fracture, the main goal of treatment for fractures of the acetabulum and pelvis is to return the patient to their pre-injury functional level, to the greatest extent possible. This means returning comfortably to daily activities – work and play. Physicians, nurses and rehabilitation specialists design a course of treatment that seeks to get the patient back to full strength and with the range of motion that they had before the injury.

To achieve these goals, proper alignment of the bones during healing is vital. Patients with acetabular and pelvic fractures often have displacement. In other words, the bones are not in proper position and must be realigned, or put back into place. Physicians use the term reduction to describe this process.

If a joint surface malheals (that is, with irregularities), the cartilage that lines the joint will rub together and wear down, setting the stage for severe arthritis of the joint, loss of motion, decreased function and pain.

Nonsurgical treatments

Treatment for patients with pelvic fractures is based on a number of factors including the type of fracture, the stability of the pelvis, and the degree of displacement of the bones. The orthopedic surgeon uses information gathered through physical examination, conventional radiographs and CT scans to make this determination. Patients with a stable pelvic fracture – without displacement or dislocation--are the most likely candidates for nonsurgical treatment. Some may require closed reduction (realignment without an open surgical procedure) under anesthesia with or without external fixation.

Some patients with fractures of the acetabulum itself may also be treated nonsurgically. Usually, this treatment is selected for patients who do not have displacement and/or those who may not be able to tolerate surgery, such as individuals with significant medical problems, infections or severe osteoporosis. Closed reduction is done either through manipulation conducted while the patient is under anesthesia or by putting the patient in traction.

Surgical treatment

Realignment of the bones may be done either as an open reduction, in which the orthopedic surgeon makes an incision to directly manipulate the bone, or as a closed reduction, in which this incision is not necessary. Once the bones are realigned, the surgeon uses internal or external fixation to hold the bone in proper position during healing. Metallic devices including wires, pins, screws, and plates are used.

Radiograph of the pelvis following open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) of a complex comminuted

fracture of the left acetabulum, hemipelvis and pubic symphysis.

Patients with pelvic fractures may require one or more surgical procedures. The surgeon may begin with an External Fixation (Ex-Fix) technique in which an open or closed reduction is performed and the bones are then held in place using an external fixator, or frame. This is done by threading pins into the bone on either side of the fracture. These pins are then connected to rods outside the skin, which form a frame.

While the Ex-Fix technique is sometimes the only procedure needed to repair a fractured pelvis, some patients require additional surgery or surgeries in which plates and screws are used internally to hold the bones in place. Depending on the site and complexity of the fracture, the surgeon may have to fix the front of the pelvis, the back of the pelvis, or both. Separate operations may be needed for each area that needs treatment.

Patients with acetabular fractures often require an Open Reduction with Internal Fixation (ORIF), especially those patients who also have displacement of the joint. The surgeon realigns or reduces the bones as precisely as possible to prevent the development of post-injury related problems, especially arthritis. The bones are rigidly fixed with plates and screws to prevent future displacement and allow for rehabilitation to begin as quickly as possible.

Fractures of the acetabulum are usually not treated for 5 to 10 days following the injury. Because the patient experiences significant bleeding with this fracture, the orthopedic surgeon must wait for the patient's own clotting mechanisms to go into effect – usually within three to five days. During this period the patient may be in traction to prevent additional injury.

Preoperative procedures

Patients scheduled for surgery undergo a number of tests. These include:

- Blood tests

- An electrocardiogram (or EKG) that tests the electrical activity of the heart

- A chest X-ray to ensure that the lungs have not been injured and have no fluid in them and that the patient has no infection of the lung (pneumonia)

- Conventional radiographs (X-rays), computerized tomography (CT scan), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): Each of these tests helps the surgeon get as much information as possible about the fracture before beginning surgery. CT scans are particularly useful since they allow the physician to see the fracture in several planes and also see a 3D model of the fracture on a computer monitor

- Magnetic resonance venogram (MRV): Assesses the patient's veins. Many patients with fractures of the pelvis and acetabulum develop blood clots in the veins of the pelvis, thighs or lower legs. If the clot travels through the body to the lungs it is called a pulmonary embolism and can interfere with the patient's breathing. If the MRV shows that a clot is present, treatment for the clot is immediately started. This may include placement of an Inferior Vena Cava Filter, that is a "strainer" in the major vein to the heart to prevent any blood clots going to the lungs (pulmonary embolism).

At HSS all surgery patients with fractures of the pelvis and acetabulum are given small preoperative doses of heparin (an anticoagulant), a drug that prevents clotting. Patients continue to take an anticoagulant (coumadin) after surgery until the physician has ruled out any further danger of clotting.

In addition to these tests, doctors and nurses frequently check the patient's pulses, the feeling in the injured limb, and ask about any strange sensations such as tingling or numbness in the limbs.

Postoperative care

Following surgery, managing the patient's pain and managing any complications that arise due to the injury are primary concerns.

Initially, pain medication will be given by injection. However, many patients are able to use a pump that controls the amount of pain medication given. This is known as patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) and offers patients the benefits of managing his or her pain. Since there is a maximum dose that can be delivered at any given time, there is no danger that the patient will receive too much medication.

Other medications that may be given include anticoagulants to thin the blood and avoid the development of blood clots, and Indocin, which prevents bone formation in areas around the muscles. (See "Complications" for more on why these drugs are given.)

Patients are encouraged to get up and out of bed as soon as possible, since doing so helps to avoid some of the complications associated with these injuries. A regimen of physical therapy is followed to maintain muscle strength and range of motion during recovery.

After surgery to repair a pelvic fracture or fracture of the acetabulum, many patients continue to feel the effects of damage to nerves that might have occurred during the traumatic event or the surgery. Important branches of the lumbar and sacral nerves may be either stretched or torn, especially in the case of unstable pelvic fractures. Injuries to the nerves result in decreased feeling in a limb and/or difficulty or inability in moving part of the limb. It is difficult to predict whether these nerves will fully recover. However, the majority of patients do regain some sensation and function of the limb within six to eighteen months after their injury.

What are the complications of surgery for a broken pelvis?

Throughout treatment and recovery, doctors and nurses are watchful for the following potential complications:

- Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: Blood clots that may form in the veins of the pelvis, thighs, and/or lower legs and may travel to the lungs.

- Pneumonia: An infection of the lungs that may affect any patient who is confined to bed and cannot expand his or her lungs as fully as they normally do.

- Skin Problems resulting from being in one position for a long period of time

- Muscle Complications due to inactivity.

- Heterotopic Ossification, a condition in which the body mistakenly forms bone in an area where there is normally muscle; prompt treatment is required to prevent this new bone from interfering with joint movement.

- Damage to the Head of the Femur: if the articular cartilage lining of the joint is affected in an injury to the pelvis, and particularly in fractures of the acetabulum, it's important to keep the surfaces of the joint from rubbing together-and to avoid the risk of future development of arthritis. Preoperatively, traction or a system of ropes, pulleys and weights are used to relieve pressure in the joint. Obviously, surgery with open reduction and internal fixation is performed to realign the joint with enough stability to allow immediate mobilization and hence preserve the smooth lining of cartilage and avoid subsequent arthritis.

- Avascular Necrosis of the Head of the Femur: Patients with a dislocated hip and/or fracture of the acetabulum may have disrupted blood flow to the head of the femur (the ball in the hip joint). This can result in death and collapse of bone tissue and hip joint arthritis.

- Nutritional Problems: The body requires more protein and calories during healing.

- Constipation resulting from inactivity.

- Infection at the site of the injury

Patients who have suffered a traumatic accident or injury may experience psychological distress over changes in their appearance and physical functioning. The shock of becoming an accident victim may also linger. As with a serious illness, the patient may wonder "why me" and be searching for reasons the accident occurred. Difficulty sleeping and coping with the pain associated with recovery are not uncommon. Patients with pre-traumatic depression or who are experiencing other stressful life events are more prone to experience psychological difficulty connected with their fracture.

In many cases, the passage of time eases these symptoms. At HSS patients and their families have telephone access to trauma nurses with extensive experience in this field. Often they are able to address the questions and concerns that arise. When necessary, the patient's physician may recommend contact with a social worker or psychologist.

Outcomes

The outcome of surgery for a pelvic or acetabular fracture is dependent on a variety of factors including: the extent of injury including injuries to the head and other organs, the health of the patient prior to the injury, and whether this is the patient's first surgery for the condition.

Pelvic fractures and the multiple injuries that often go along with them are potentially life-threatening. In addition, unfortunately, even those patients who survive these injuries and whose bones are successfully realigned and healed, may have a significant degree of long-term disability, and chronic pain is not uncommon. Many have injury to the genitourinary system that can result in incontinence and impotence. The best chance for a good recovery lies in receiving excellent care from specialists who are experienced in rapid decision-making following a traumatic accident.

By itself, a fracture of the acetabulum is generally not a life-threatening injury. (Of course, some patients with these fractures will also have other serious injures.) And, thanks to advances in treatment over the years, especially surgical reduction and stabilization techniques, 80% to 85% of patients, can expect a good to excellent recovery following surgery, provided that the hip can be properly aligned and fixed.

On the second day following surgery for an acetabular fracture, patients are usually able to get out of bed. Crutches must be used for eight weeks following surgery, but by 12 weeks most people are able to walk unassisted. If they are otherwise in good condition, most people recover fully within four to six months and are able to resume recreational activities at that time.

For individuals who have received initial treatment for their pelvic and acetabular fractures elsewhere, who have not healed properly, and are now seeking corrective surgery, a complete recovery can be more difficult to achieve. But previous surgery is not necessarily an obstacle to a good outcome following a second surgery, but this requires an experienced team, as this is the most complicated and difficult surgery of all.

While many of us have become accustomed to the amazing strides achieved by medical science, it's worth noting that these good results following acetabular fractures are remarkable. This progress is due in large part to long-term studies conducted by two French researchers, Judet and Letournel, who identified the common fracture problems and provided key information on the best way to gain access to the fracture with the least amount of injury to the patient. Based on their findings, better instruments and surgical techniques have evolved. Physicians also have a better understanding of how to avoid complications and of the healing process. More recently, additional information about the fracture is achieved through visualizing techniques such as CT and MRI scans. Before any of these developments occurred, patients with acetabular fractures had a far less promising outlook. Most ended with painful arthritic hips, and in young patients a hip bone fusion, which resulted in drastically limited mobility.

The Orthopedic Trauma Service at HSS

The Orthopedic Trauma Service at HSS is a team of physicians, nurses, technicians, nutritionists and therapists who have been assembled to provide the best care possible to those people who have had a major musculoskeletal injury. We specialize in patients with complex injuries including fractures of the pelvis, acetabulum, other major joints (elbow, shoulder, hip, knee and ankle), calcaneus and long bone injuries.

Many of the patients treated for these fractures at HSS are referred by physicians at other institutions, or at the request of a family member. This process starts with a phone conversation between Dr. David L. Helfet, the Director of the Orthopedic Trauma Service and the outside physician who is currently treating the patient. After the patient's need for treatment at HSS has been established, the trauma nurse at HSS speaks to the nurse currently in charge of the patient's care to obtain a head-to-toe assessment of the patient's condition. This information is relayed to the HSS/NYPH staff, in order to determine what other injuries are present, whether the patient must first be transferred to the ICU and evaluated by the General Surgery Trauma Team (NYPH) or whether they are cleared and ready for surgery right away. In most cases, patients are not transferred until they are stabilized at the outside institution and are able to undergo surgery the day following their arrival at HSS/NYPH.

In some cases, it may be necessary to delay transfer until it has been determined that the patient is stable for transfer and there is no ongoing injury present. Failing to do this could result in serious and permanent disability. While this waiting period can be difficult for patients and their families, this is a precaution that must be observed for the patient's safety.

Staff members from each hospital coordinate the safe transfer of the patient, which may be done by car, ambulance, plane or helicopter depending on individual circumstances. Owing to the staff and the hospital's reputation for excellence, trauma patients have been transferred to HSS/NYPH from all over the world for treatment of these fractures.

Frequently asked questions and answers

Q: Why do I need surgery for a broken pelvis?

If your surgeon recommends surgery it is because you have a displaced fracture and there is an incongruity in the acetabulum. Normally the acetabulum is a smooth cup, congruent with the femoral head, allowing for frictionless motion of the femoral head. If the fracture heals in the displaced position and there is a "step off" then the cartilage on the femoral head will wear away causing posttraumatic arthritis. This is painful and can be very debilitating and possibly may lead to a hip fusion or total hip replacement. The goal of the surgery is to:

- restore the normal shape of the acetabulum

- decrease pain and allow for early ambulatory function

- decrease the chance of post-traumatic arthritis

- delay or avoid the necessity for a total hip replacement

Q: How long will I be in Hospital for Special Surgery?

The typical inpatient stay for acetabular fracture surgery is 7 to 10 days.

Q: Will I have a brace or cast after surgery?

No. The fracture is reduced and stabilized internally with plates and screws.

Weight bearing will be limited for eight weeks following the surgery to allow the bone to heal.

Q: Will I have a limp after the surgery?

Most patients that undergo aggressive rehabilitation to restore muscle strength and flexibility do not have an abnormal gait but can walk normally.

Q: When do my sutures or staples come out?

Ten to fourteen days after surgery the patient returns to the surgeon for a post-operative check-up. At this time, the wound is examined and the sutures or staples are removed. The patient may shower or bathe after they are removed.

Q: Do I have to go to a rehabilitation facility after my stay at Hospital for Special Surgery?

No. Most of our patients do return home after their surgery. Physical therapy in the hospital insures that each patient is independent on a walker or crutches and is able to manage stairs. However, there are certain situations where a patient prefers to go to a rehabilitation facility post-operatively and this can be worked out in the hospital with the trauma social worker.

Q: When can I return to work?

Typically patients with these injuries who do manual labor are on temporary disability for six to nine months following surgery. Those individuals that have jobs that are less physically demanding, ie. desk jobs, return to work much earlier (some even after a few weeks). However, each case is evaluated on an individual basis.

Q: How much pain will I be in after surgery?

Pain is very subjective, however, at HSS a complaint of pain is taken very seriously and every effort is made to adequately control the pain. Most patients do go home with oral medication.

Q: How long do I need to go to physical therapy?

Strengthening and flexibility exercises are very important components of the rehabilitative process. Most of the exercises necessary to increase strength such as running on the treadmill and or using the stationary bicycle do not commence until full weight bearing at eight weeks. Most patients will continue with physical therapy for 6 to 12 months after surgery.

Q: How long will I be under the care of my surgeon?

Initially you will see your surgeon every couple of weeks and have conventional radiographs. At about six months you will return approximately every three months for X-rays followed by annual check-ups. Additional visits are unnecessary unless a problem arises.

Q: Is there any medication I can take or anything I can do to expedite the healing process?

No. A fractured bone typically takes eight weeks to heal. There is no medication to speed up the healing. A healthy diet and adequate sleep are always recommended. Of note, smoking has been known to delay healing and sometimes arrest healing all together.

Q: My family member was brought to the hospital today with a fracture of the acetabulum, but we were told that surgery to repair the broken bone won't take place for at least a week even though she doesn't have other injuries. Shouldn't she be treated right away?

This delay will actually protect your relative. An acetabular fracture is accompanied by a significant amount of bleeding. Over the course of the next three to five days bleeding will stop with the help of the body's own clotting mechanisms. Only after this happens is it safe to proceed with surgery.

Q: I will be undergoing repeat surgery for a pelvic fracture that happened three years ago. What are my chances for improved function and good recovery?

Unfortunately, there's no precise answer to this question. The success of the surgery depends on the potential for improving the alignment of the broken bones, your overall health, and ability to adhere to a rehabilitative program. While it is always easier to get good results with an initial repair of a fracture, previous surgery does not necessarily mean that you will not experience significant improvement.

Q: Why is it sometimes necessary to have more than one operation to fix a pelvic fracture? Can't the surgeon fix everything at once?

In many cases, the surgeon must approach the pelvic bones from different directions in order to complete the repair. Each of these approaches can require a separate surgery.

Q: I understand that I will have to start taking a blood thinning drug before undergoing surgery for an acetabular fracture. Will that put me at greater risk for excessive bleeding?

Your physician has prescribed this medication for you to guard against the development of a blood clot in the veins of your pelvis, thighs or lower legs. Should such a clot develop and travel to your lungs, it can interfere with breathing and pose a significant danger. You will be taking a very low dose of this medication and will be watched carefully to ensure that no excess bleeding occurs.

Q: My grandmother broke her acetabulum after a simple fall in her home. How could this happen?

Your grandmother probably has osteoporosis, a condition in which the bone density decreases and the bones become more fragile and likely to break on impact. If she has not been assessed for this condition before, her physician will certainly do so and recommend a course of treatment to help prevent future fractures.