Shoulder Separation and Dislocation: An Overview

An Interview with Dr. Frank A. Cordasco

This article is intended for primary care physicians and other medical professionals, but may also be of interest to patients. You may also explore physician courses related to shoulder injuries at HSS eAcademy®.

Overview

For many individuals, a diagnosis of shoulder instability—either a shoulder separation involving the acromioclavicular (AC) joint or a shoulder dislocation of the glenohumeral (GH) joint—can initially result in some confusion. Making distinctions between these conditions and gaining a better understanding of the complex nature of the shoulder can help explain both diagnosis and treatment options.

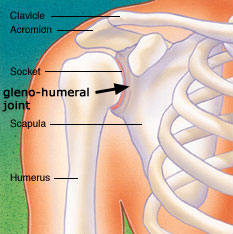

The shoulder is actually made up of four different articulations or joints: the AC joint, where the acromion (the upper portion of the scapula) meets the collarbone or clavicle; the glenohumeral joint, where the humerus (the large bone in the upper arm) joins the glenoid, the cup-like structure on the scapula; the sternoclavicular joint, where the clavicle meets the sternum; and the scapulothoracic articulation where the scapula meets the thoracic (chest) wall.

Together these articulations make up what physicians refer to as the “shoulder girdle.” A network of ligaments (which act as static, immobile stabilizers), muscles (which act as dynamic, moving stabilizers) and other soft tissue supports these joints and hold them in proper alignment.

Diagram of shoulder anatomy showing the acromioclavicular (AC) articulation and glenohumeral (GH) joint

“Movement in this part of the body is more complex than in other large joints, such as the hip or knee. Each time the arm is raised, not only does the ball of the humerus move in the socket of the glenoid, but the clavicle and the acromion rotate 40 degrees with respect to one another, while the scapula moves on the chest wall,” explains Frank A. Cordasco, MD, MS, an associate attending orthopaedic surgeon at Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS).

A healthy shoulder allows a wide range of motion that encompasses activities of everyday living as well as athletics. Shoulder instability is diagnosed when some type of injury affects the complex of bones and soft tissues. It may occur as the result of a single trauma or as the result of a series of microtraumas (smaller injuries that accumulate over time). The most commonly occurring injuries to the shoulder are those involving the acromioclavicular (AC) joint and the glenohumeral (GH) joint.

What is shoulder separation?

Shoulder separation describes the condition in which the ligaments connecting the AC joint are injured and the acromion begins to move away from the clavicle. Because the injury is a disruption in the suspensory mechanism that keeps the arm suspended from the clavicle and close to the chest, it can be very disabling. Many patients with a shoulder separation develop the problem during athletic activity, but shoulder separation can also result from accidents such as falling on the tip of the shoulder.

Shoulder separation occurs along a spectrum of progressive injury, ranging from a sprain or partial tear of the ligaments making up the least severe type of separation, to a complete tear of the major ligaments that support the joint, resulting in more severe injury or separation.

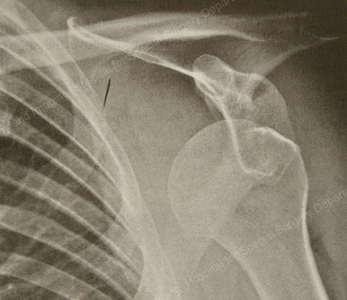

Orthopedists use the Rockwood classification system—a numerical scale from Type I to VI—to help define their diagnosis, which is made on the basis of physical examination as well as X-ray. A Type I injury indicates minimal injury or sprain of the AC joint, while more severe injuries are indicated by a higher number, Type VI being the most severe.

X-ray image of a shoulder separation

How is shoulder separation treated?

Treatment of shoulder separation depends on a number of factors, including the severity of the separation, the patient’s age, and their willingness and ability to modify their activities. Among competitive or elite athletes - including those at the high school or collegiate level - treatment decisions are also guided by whether the problem arises pre-, during, or post-season. Athletes who are mid-season may be treated non-operatively (depending upon their sport and position) so that they may continue participating in their sport, then opt for surgical treatment in the off-season.

Treatment options

Types I-II:

Lower grade shoulder separations (Types I and II) are usually treated non-operatively, with initial rest followed by a course of physical therapy to maintain flexibility and range of motion and to strengthen surrounding muscles.

Type III:

While Types I and II comprise partial separation, Types III and above are complete separations. Patients with a Type III shoulder separation represent a group for whom the choice of treatment may be somewhat more controversial.

“Traditionally, patients with these injuries may have undergone non-operative treatment, but today we tend to recommend surgical repair for a complete AC separation, based upon the patient’s age and activity level,” says Dr. Cordasco. Although a patient with this type of shoulder separation may feel better in six to eight weeks after the injury, the long-term effects of the higher grade separation may become problematic.

“Because the acromion drops down, the mechanics of the muscles that are functioning to move the arm are altered. With ten, fifteen, or twenty years of repetitive motion, there may be more wear of the rotator cuff muscles, and tendons,” he says. Patients may develop a condition known as secondary impingement syndrome, which is characterized by pain, weakness, and loss of motion.

In patients with Type III separations, age is a significant consideration. “In a 20-year-old, we assume the patient is going to live for another 50 or 60 years,” says Dr. Cordasco. “When I see a young patient who’s going to remain active - particularly a throwing athlete whose dominant shoulder is effected - I often recommend surgical treatment.” However, he adds, patients seeking treatment at their community hospital, where newer techniques are potentially unavailable, may not be offered this option. Conversely, in a patient in his or her “middle years” who is willing to alter his or her activities, non-operative treatment may be appropriate.

Types IV-VI:

Patients with separations that are graded as types IV, V, and VI are usually advised to undergo surgical treatment to repair ligament injury, a procedure that may be performed either with an open incision or with the aid of arthroscopy. In arthroscopic surgery, the orthopaedic surgeon is able to repair the injury using miniaturized instruments inserted in the shoulder through small incisions. A small camera inserted through another incision helps guide the procedure. “My preference is to perform the procedure using an arthroscopic approach which we devised here at the Hospital for Special Surgery” says Dr. Cordasco.(1,2)

Repair of the ligaments requires a graft from another location, which may be in the form of an autograft (obtained from the patient) or an allograft (obtained from a cadaver).

“Completely torn ligaments will not heal on their own,” Dr. Cordasco explains,” the goal of surgery for shoulder instability is to restore the anatomy by reconstructing the ligaments. Doing so gives you the optimum outcome. Attempts to alter the anatomy are not as successful.”

In the past, surgeries to repair shoulder separation often involved transfer of tissue to support the joint (a popular technique was known as the Weaver-Dunn technique); these reconstructions met with variable outcome and had a higher failure rate, as well as other long-term problems.

Results

Surgical treatment of shoulder separation has a high success rate, with long-term results of arthroscopic procedures showing comparable results to those of traditional open surgery. However, experts concur, in the short-term, that arthroscopic treatment is more comfortable for the patient and has a shorter recovery period associated with it. Arthroscopic surgery is not an option for all patients, including those who are undergoing revision surgery for an injury that was not treated successfully in the past.

Interestingly, patients with less severe forms of AC separation (Types I and II) may be at greater risk for developing the long-term complication of AC arthritis. This is due to the disruption of the joint surfaces that occurs with the injury that may, over time, result in erosion of the articular cartilage or joint cushion, and subsequent “wear and tear” arthritis. In untreated type III, IV, V, and VI separations, other long-term complications may ensue, but because there is no contact of the joint surfaces, the risk of developing separation-related arthritis is absent.

Shoulder Dislocation—the Glenohumeral (GH) Joint

Shoulder flexibility, as measured in the glenohumeral joint, varies greatly from person to person, with all individuals falling somewhere within a spectrum. Certain athletes may fall on either end of the extreme. For example, most elite swimmers and professional dancers tend to have very loose shoulders; whereas an NFL offensive tackle or an Olympic marathon runner may have less movement in the joint.

What is shoulder dislocation?

Shoulder dislocation occurs when the connection between the humerus and the glenoid—the ball and socket joint in the shoulder (see image above) becomes unstable (3,4,5). As with shoulder separation, an injury to the ligaments that stabilize the joint is involved. In most cases, the labrum, a layer of cartilage that lines the glenoid bone and serves as the attachment site for the ligaments, will be torn. Less commonly, the ligament may fail from the humeral or “ball” side of the joint; this has been termed a HAGL (Humeral Avulsion of the Glenohumeral Ligament) lesion.

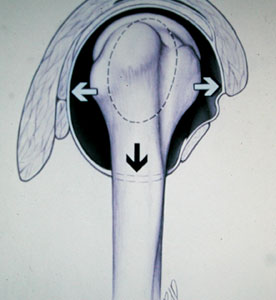

Individuals with this condition most commonly have anterior shoulder instability (3,5), in which the humeral head shifts toward the front of the body; or less commonly posterior instability, in which the head moves toward the back of the body; or multidirectional instability (4), in which the shoulder is loose “globally” (in every direction). When tears of the labrum occur anteriorly (in the front of the socket) they have been termed “Bankart” tears. If they occur on the upper part of the glenoid (superior), they have been termed SLAP tears (Superior Labrum Anterior Posterior). SLAP tears often occur in throwing athletes and swimmers (6).

Diagrams of glenohumeral (GH) dislocation – anterior dislocation (top) and multidirectional dislocation (bottom)

X-ray image of glenohumeral (GH) dislocation

Anterior dislocations are the most common type. Individuals with this condition may feel that the shoulder has “slipped” or “locked” out of place. In some settings, as when an athlete develops the injury during competition, a trainer or coach may be able to move the humeral head or "ball" back in its correct position - a procedure orthopedists refer to as reduction. Because reduction can be painful, however, in most cases it is performed with the patient under intravenous sedation in a hospital setting.

Whether they are competitive athletes or not, most people with shoulder dislocations have injured themselves playing a sport. However, other forms of blunt trauma - such as a fall down a flight of stairs or being knocked over by a large wave in the ocean - may also result in a dislocation of the shoulder. Posterior dislocations may also occur as the result of a bicycle accident as well as equestrian or motor vehicle accidents. They have also been linked to a seizure disorder. “When the body undergoes a seizure or an electric shock, the way the muscles fire may drive the humerus (ball) out of the socket and toward the back of the body instead of the front,” says Dr. Cordasco.

How is shoulder dislocation treated?

Once the dislocated shoulder has been reduced, orthopedists base their treatment recommendations in large part on the degree of the injury and the patient’s chances of experiencing a recurrence. The age of the patient at the time of the first dislocation is inversely related to recurrence rate, and the activity level of the patient is directly related to the recurrence rate, according to Dr. Cordasco. “Therefore, a high intensity adolescent athlete who requires reduction is probably best served by surgical repair.” On average, a 50-year-old patient is much less likely to have a recurrence of the dislocation (however, older patients are more likely to sustain a tear of the rotator cuff tendons at the time of dislocation.)

Non-operative treatment

Non-operative treatment is appropriate for some patients, including older individuals and those who are going to modify their activities, and those with atypical dislocations in which no injury to the ligament is seen on MRI. “Physical therapy will not restore anatomy, but the goal is to strengthen the dynamic stabilizers, the muscles, to compensate for the torn ligament complex,” explains Dr. Cordasco.

Surgical Repair

Surgical treatment of a shoulder dislocation involves reattachment of the torn ligaments - and labrum - to the bone and fixation with bioabsorbable (non-metallic) suture anchors. The surgery may be performed with either an open incision or with the aid of arthroscopy. These outpatient procedures are conducted with the use of regional anesthesia during surgery.

As with surgery for AC separation, arthroscopic repair offers the advantages of a less painful, and more rapid, recovery. The time required to return to collision sports is not dependent upon whether the procedure is performed arthroscopically or with open surgery; however, the short-term recovery is much improved with the less invasive procedure. In addition, some data suggests that patients undergoing this type of surgery regain increased rotation of the shoulder compared with those undergoing open procedures. Arthroscopic techniques are performed through small puncture sites with minimal scarring.

“Arthroscopic techniques are well established and are the standard of care for shoulder dislocation at Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS),” Dr. Cordasco notes. “We think it’s the best available treatment because it restores the anatomy with a minimally invasive procedure. However, there is a role for open surgery as well, usually to address soft tissue or bone insufficiencies.”

Results

Postsurgical recovery from a corrected shoulder dislocation involves a regimen of physical therapy for several weeks. Younger patients, especially those who participate in what Dr. Cordasco and his colleagues characterize as a collision athletic activity - such as football, basketball, lacrosse, or hockey - can expect to have a high recurrence rate, and are usually candidates for arthroscopic repair of the injury. A return to rigorous athletic activities involving collision requires a 6- to 9-month postsurgical recovery period and throwing athletes may require a year or more to return to their prior level of competition.

Although recurrent dislocation is still possible following surgical repair, the incidence is much lower than if the initial dislocation is left un-repaired in the young athletic population. When a dislocation does recur, however, the reasons range from recurrent injury and inadequate healing to poor surgical technique.

Generally, however, Dr. Cordasco remarks that patients tend to enjoy a very positive success rate after surgery. “Results,” he says, “are overall 85-90% good to excellent.”(3,5,6,7)

For more information on treatment of shoulder instability at HSS, please contact the Physician Referral Service at 1.877.606.1555.

References

1. Baumgarten KM, Altchek DW and Cordasco FA: Arthroscopically Assisted Acromioclavicular Joint Reconstruction, Technical Note. Arthroscopy, 22:228-229, 2006.

2. Tomlinson DP, Altchek DW, Davila J, Cordasco FA: A Modified Technique of Arthroscopically Assisted AC Joint Reconstruction and Preliminary Results. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 466:639-645, 2008.

3. Pearle, A and Cordasco FA: Shoulder Instability. In: Vaccaro AR ed: Orthopaedic Knowledge Update 8. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, Rosemont, Illinois, Chapter 25, p.283-294, 2005.

4. Cordasco FA: Understanding Multidirectional Instability of the Shoulder. Journal of Athletic Training 35(3): 278-285, 2000.

5. Dodson CC, Cordasco FA: Anterior Glenohumeral Joint Dislocations. Orthop Clin North Am, 39:507-18, 2008.

6. Brockmeier SF, Voos JE, Williams RJ 3rd, Altchek DW, Cordasco FA, Allen AA: Outcomes After Arthroscopic Repair of Type II SLAP Lesions. J Bone Joint

Surg, 91A: 1595-1603, 2009.

7. Voos J, Livermore R, Feeley B, Altchek DW, Warren RF, Williams RJ, Cordasco FA, Allen AA: , Prospective Evaluation of Arthroscopic Bankart Repairs for Anterior Instability, Am J Sports Med, In Press 2009

Summary prepared by Nancy Novick

Authors

Attending Orthopedic Surgeon, Hospital for Special Surgery

Professor of Orthopedic Surgery, Weill Cornell Medical College