Hip Dislocation

This overview discusses unintentional, traumatic hip dislocation injuries. For information on developmental hip displacement in children and teenagers, see Hip Dysplasia. For information on the hip dislocation corrective surgical technique, see Surgical Hip Dislocation.

A traumatic hip dislocation is when the ball of the hip joint is pushed out of the socket. This injury most commonly occurs during an auto collision or a high-impact fall, workplace or sports injury, especially those that also result in a broken leg or pelvis. A dislocated hip can lead to serious long-term debilitating problems, especially if it is severe or not adequately treated within hours of occurance. If a person experiences any forceful impact that results in serious hip pain or pain in the groin, leg or even the knee, he or she should be examined by orthopedic specialist to determine whether there is a hip dislocation.

Anatomy of the hip joint

The hip joint is a ball-and-socket joint. The ball, at the top of the femur (thighbone) is called the femoral head. The socket, called the acetabulum, is a part of the pelvis. The ball rotates in the socket, allowing the leg to move forward, backward, and sideways. Smooth cartilage lines the ball and the socket help them glide together and secure the joint.

In most hip dislocations, the femoral head of the thighbone is forced out of the acetabulum toward the rear (posterior dislocation). Less often, the displaced ball is pushed out forward from the pelvis (anterior dislocation).

X-ray: Anterorposterior (front to back) view of the pelvis. There is a posterior

dislocation of the left hip (at the arrow). The right hip is in its natural position.

Hip dislocation is very painful and can cause tears or strains in adjacent blood vessels, nerves, muscles, ligaments and other soft tissues. The most serious complications associated with hip dislocations are avascular necrosis (bone death), and sciatic nerve damage. The sciatic nerve extends from the lower back to the upper thigh and then divides into the tibial and common peroneal nerves, which enable movement of the ankles and toes. Significant damage to these nerves can limit a person's mobility, sometimes permanently.

Diagnosis

To diagnose a dislocated hip or other source of hip pain, an orthopedist will conduct a physical exam and order imaging of the hip in the form of an X-ray, MRI and/or CT scan.

Treatment

Nonsurgical reduction by manipulation: Usually, an orthopedist can simply push the ball back in by hand while the patient is under anesthesia. If, however, the imaging reveals fractures or significant damage to soft tissues, blood vessels or nerves, orthopedic surgery may be required.

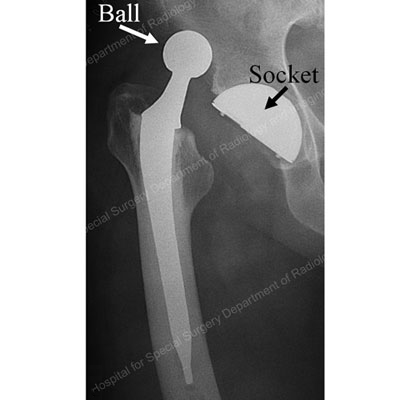

Hip dislocations after a total hip replacement

Hip dislocations in people who have had a total hip replacement (THR) are relatively infrequent among otherwise healthy people who follow the precautions provided by their orthopedic surgeon and physical therapist. But higher rates of dislocations occur in certain hip replacement patients: the elderly, those with other physical disabilities, those who had a THR after a hip fracture or after other hip surgeries, and in those who had one or more hip dislocations prior to a THR (for example, if muscles and ligaments around the hip were disrupted from the prior dislocation and weakened as a result). If a patient experiences multiple dislocations after THR, he or she is usually a good candidate for a hip revision surgery.

X-ray of a dislocated total hip replacement implant,

where the ball has been forced out of the socket.

Hip Dislocation Success Stories

In the news