Hip Revision (Revision Total Hip Replacement)

Total hip replacement is a durable and highly successful operation and the associated implants usually last about 15 to 20 years. However, as with any device, hip replacement prostheses can experience wear, mechanical failure, and/or metallosis. Metallosis is an uncommon but serious complication in which an implant degrades or corrodes and releases microscopic metal particles into the surrounding soft tissues or the bloodstream. Implants that fail in any of these ways must be exchanged for new ones in a procedure called a revision total hip replacement.

As younger, middle-aged patients increasingly opt to have hip replacement to maintain active lifestyles as they age, subsequent hip revision surgeries are becoming more common. However, a revision of a hip replacement can be more complex than the initial operation (the primary hip replacement). It should not be regarded as or compared to "changing the tires on a car." The results of surgery and the durability of the revised hip replacement are sometimes less predictable than those of the primary operation. With every revision surgery, there is some loss of muscular mass, bone, or both. The surgery also takes longer and, for all the reasons noted above, has a higher likelihood of potential complications than a primary surgery.

What is hip revision surgery?

Hip revision surgery (also called revision total hip replacement) is a reoperation (second surgery) to address a failed hip replacement implant or a complication from a previous hip replacement. In this procedure, some or all of the prostheses from the initial hip replacement are removed and new ones implanted. The extent of the revision required depends on the mode and severity of failure of the current implants.

Hip revision operations are performed relatively infrequently. In the United States, there are approximately 18 revision hip replacements performed for every 100 hip replacements.

Who needs a hip revision surgery?

With modern materials, implants, and polyethylene, the majority of patients over 60 years of age who receive a hip replacement retain the prosthesis for life. However, some patients may need one or more revisions of a hip replacement, particularly if the initial hip replacement surgery is performed at a young age or infectious or mechanical complications with the first prosthesis occur.

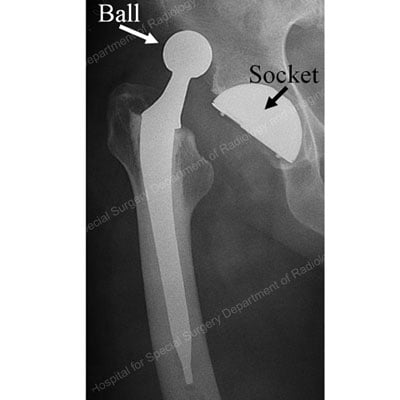

Preoperative investigations of patients who will undergo revision surgery are more extensive than those for patients who will undergo a primary surgery. Often, special radiographic (X-ray) projections, CT scan, MRI or EOS imaging of the hip may be necessary to determine position and fixation of the replacement parts (components), and to determine precisely the extent of bone loss around a failed implant.

X-ray of a primary total hip replacement showing the ball, socket and stem implants

A preoperative aspiration (fluid sample) and/or special blood work may be needed if the surgeon suspects an infection in the failed hip. (Find a hip revision surgeon at HSS.)

What are the signs of needing a second hip replacement?

Symptoms indicating the need for hip replacement revision can include hip pain (especially while walking), stiffness or difficulty walking, instability, new grinding or clicking sounds, inflammation and/or experiencing multiple hip dislocations or, fracture of the femur or pelvis bone around the implant. These and other signs suggest one or more of the following problems are occurring:

- infection

- repetitive (recurrent) dislocation of a hip replacement

- mechanical failure (implant wear and tear – loosening or breakage)

- periprosthetic femoral fractures (a break in the femur near or around the prosthesis)

- metallosis (the release of microscopic metal particles from the implant into the body)

Repetitive hip dislocation

As mentioned above, a hip replacement implant's structure resembles that of the natural hip (a ball and socket). For a hip replacement to function well, the ball must remain inside the socket at all times. Two key factors keep the ball inside the socket: (1) the alignment and fit of the ball and the socket, and (2) forces generated by the strong muscles and ligaments around the hip joint.

A hip replacement is designed to have a large range of motion. However, trauma or certain hip positions can force the hip ball out of the socket. This condition is called a dislocated hip or hip dislocation.

Dislocations in people who have had a hip replacement are relatively infrequent, particularly in the healthy patient who carefully follows precautions given by their surgeon and physical therapist. However, some people are predisposed to this complication.

X-ray of a dislocated total hip replacement prosthesis showing the ball forced out of the socket

This can include elderly patients, patients with lumbosacral fusions or spine deformities, patients with connective tissue disorders, or those who got a hip replacement after having a hip fracture or multiple prior hip surgeries.

Anyone with a replaced hip who has suffered a hip dislocation is then predisposed to have them again, because the dislocated ball disrupts the important muscles and ligaments around the hip. Multiple dislocations are infrequent, but in patients who have suffered multiple hip dislocations, the orthopedic surgeon may recommend revision surgery.

Revision surgery is effective in preventing a new dislocation. Prior to surgery, the surgeon may request imaging studies to determine the exact position and orientation of the different parts of the replacement. One or more parts may need to be reoriented or completely exchanged during the revision.

In certain instances, the surgeon may use a device that “captures” the ball inside the socket (called a constrained socket). The proper healing of the soft tissues around a revised hip is most important for the success of the operation. Therefore, the surgeon may recommend wearing a brace for a few weeks after surgery. After surgery, it is important to follow the surgeon’s advice and to refrain from moving the hip into positions that can generate a new dislocation.

Mechanical failure (wear, loosening, or breakage)

The parts of a hip replacement which move against one another will slowly wear down during the regular use of the replacement. Continual, repetitive movement of the mechanical parts causes small pieces of hip prosthesis ("wear particles") to break off. Depending on the type of hip replacement, these particles can be made out of plastic, cement, ceramic, or metal.

A patient’s immune system will recognize these particles as foreign objects (not a natural part of the body) and generate an immune response (like an allergic reaction). A strong reaction to the wear particles can result in the destruction of bone tissue around the hip replacement (a condition called osteolysis). If the bone destruction is severe enough, the components of the replaced hip may become loose.

X-ray of a loose total hip replacement prosthesis showing separation of the stem from the bone (as detailed by arrows)

A loose component can move against the surrounding bone, compounding the bone loss. If the bone loss is severe enough, a spontaneous bone fracture can occur (known as a pathologic fracture).

Mechanical wear and tear leading to loosening of the prosthesis (implant) is one of the most frequent forms of mechanical failure. However, other forms of mechanical failure are possible, like breakage of the prosthesis, such as may occur during a trauma like a fall or auto collision.

During revision surgery for wear, mechanical loosening, or breakage, the surgeon will remove the worn, loosened, or broken component(s), assess the amount of bone loss, and implant new components. Frequently, a bone graft from a deceased donor (whose tissue is tested for compatibility with the patient) is necessary to rebuild the bone content lost because of the prosthetic failure.

X-ray detailing the broken stem section of a total hip replacement prosthesis

In certain instances, when a large amount of bone graft must be utilized, or when the patient’s own bone stock is poor quality, the surgeon may ask the patient not to bear full weight on the operated leg for a specified period of time after surgery.

Fortunately, with modern materials, especially with modern plastics utilized in modern hip replacements, the wear and osteolysis has significantly diminished. It is now rare to see this with modern components, but older implants or defective implants may still have these issues.

Infection of a hip replacement

Infection can occur at any time after surgery. The risk is higher during the first six weeks. The risk of “late” infections after that period is lower. Sometimes, infections unrelated to the hip – for example, in the mouth, gums, or teeth (including after regular dental procedures that involve bleeding gums), or in the lungs, urine, or skin – can cause bacteria to enter the blood stream. These bacteria can then infect tissues around the prosthesis, causing hip pain and fever.

If such a prosthetic infection occurs, the surgeon will attempt to identify which organism(s) – species of bacterium (or bacteria, if more than one) – are causing the infection. A hip aspiration may be recommended. The liquid aspirated from the hip will be sent to a laboratory and tested to determine the type of bacteria present and the antibiotics the bacteria are sensitive (susceptible) to.

Once an infection in the hip replacement has been diagnosed, several treatment options are possible. The vast majority of treatments include surgery and a course of antibiotics that specifically target the infecting bacteria. The treatment option depends on the type of bacteria and its sensitivity to antibiotics, the duration of the infection, the fixation of the hip replacement parts, and the patient’s general health. The surgeon will discuss the benefits and drawbacks of each treatment option.

The most common treatment options include performing:

- A thorough surgical cleaning of the hip replacement. This is generally recommended when the infection is discovered very early (within a few hours or days). Patients require six weeks of intravenous antibiotics and, frequently, a low dose of oral antibiotics for a long period of time (sometimes for life).

- A complete exchange of a hip replacement, done in two stages: A first stage consists of the complete removal of the hip replacement, cleaning of the bone, and implantation of a temporary cement spacer that will allow some hip motion and deliver antibiotics to the hip area. This is generally followed by a six-week course of intravenous antibiotics. The second stage consists of the reimplantation of a definitive hip replacement (generally 6 to 8 weeks after the initial operation).

- A complete exchange of a hip replacement done as a single operation, during which the infected prosthesis is removed, the bone is cleaned, and a new prosthesis is implanted. Patients require six weeks of intravenous antibiotics and, frequently, a low dose of oral antibiotics for a long period of time (sometimes for life).

Video: Animation of Hip Revision Surgery

View this step-by-step animation of a single-operation hip revision procedure.

What should I keep in mind when considering revision hip surgery?

During revision surgery, the surgeon may need to remove or exchange one or more parts of the hip replacement. The parts that are not attached to the bone can be safely exchanged with minimal to no removal of the patient’s bone. However, if the metallic parts in contact with the bone need to be changed, some bone loss generally occurs. In addition, some of the musculature around the hip will be lost, thus affecting the strength of the hip and the patient’s function after surgery. The results of revision surgery are not as predictable as those of the primary surgery. Complications are more frequent.

Is hip revision surgery recovery time different than for a primary hip replacement?

Recovery from hip revision surgery is typically longer and more challenging than that in a primary hip replacement. Each patient’s recovery time may vary but, typically, patients should expect 4 to 6 weeks of restricted movement and/or weightbearing, probably with the aid of crutches or a walker. Complete healing and restoration of mobility with physical therapy may take 6 to 12 months.

How many times can a hip replacement be revised?

One of the main goals for revision hip surgeons is to avoid further complications that would lead to necessitating another hip revision. Most patients only need one hip revision, but if complications occur, including infection, dislocation/instability, or fracture, then further revisions may be needed. It is important to seek care in the hands of revision hip experts. Surgeons at the Complex Joint Reconstruction Center at HSS specialize in the most challenging cases in joint reconstruction and treatment of implant failure.

What are the risks of hip revision surgery?

All surgeries involve risks such as infection (if one is not already present), blood clots or anesthesia or medical complications, which are all slightly elevated in the revision setting. As revision surgeries are more complex than primary hip replacements, there are additional risks complications such as a hip dislocation, nerve related issues, and damage to surrounding bone and tissue. However, newer techniques, technologies, and implants such as computer navigation for implant placement, are helping reduce risks and achieve better outcomes.

How can I prevent the need for hip revision surgery?

It is vital for a hip replacement patient to be aware of the risks of infection and implant failure, and to monitor themselves after surgery. Some of the above-mentioned forms of failure can be prevented.

Dislocations can be prevented by following the surgeon’s instructions. Some hip infections can be prevented by prompt treatment of other bodily infections and by taking antibiotics before certain dental and other procedures.

The natural wear and tear of a prosthesis generally causes no pain or discomfort. Therefore, it is very important for the patient to have his or her hip replacement regularly checked. A simple physical examination and radiographs (X-rays) are necessary at intervals designated by the surgeon. If excessive wear and/or bone loss is detected at any time, close monitoring is necessary to determine the best possible time (if any) to have the hip replacement revised.

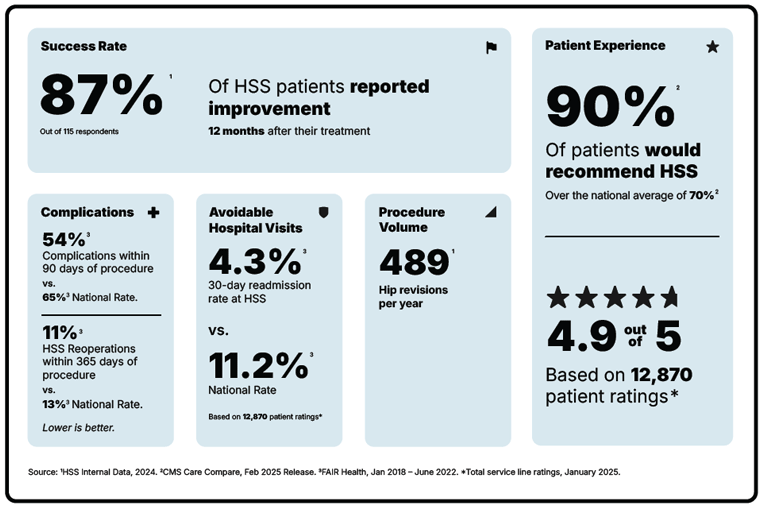

Why you should choose HSS for hip revision

Hip revision is a surgery focused on reducing pain and getting you back to the activities you love. But not all hospitals achieve the same results. Some are more reliable than others. With the help of the HSS Hospital Reliability Scorecard, you can make sure you're asking the critical questions to find the hospital that's right for you. Understanding these data points will help you make the best decision for your care:

See hospital reliability data

Medically reviewed and updated by Brian P. Chalmers, MD; and Elizabeth B. Gausden, MD, MPH, on behalf of the Adult Reconstruction and Joint Replacement Service

Hip Revision (Revision Total Hip Replacement) Success Stories

References

- Memtsoudis SG, Besculides MC, Gaber L, Liu S, González Della Valle A. Risk factors for pulmonary embolism after hip and knee arthroplasty: a population-based study. Int Orthop. 2009 Dec;33(6):1739-45. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18925395/

- Neitzke CC, Chandi SK, Gausden EB, Debbi EM, Sculco PK, Chalmers BP. Use of Computer Navigation for Optimal Acetabular Cup Placement in Revision Total Hip Arthroplasty: Case Reports and Surgical Techniques. Arthroplast Today. 2024 Jun 27;27:101347. doi: 10.1016/j.artd.2024.101347. PMID: 39071827; PMCID: PMC11282418. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39071827/