Lumbar Disc Herniations: Frequently Asked Questions

A spinal disc is a soft, rubbery structure located between the vertebral bodies (bones of the spine). The disc acts as a pad or cushion for the bone. The outer portion of the disc (the annulus fibrosus) is made up of a tough fibrocartilage.

The middle section (the nucleus pulposus) is composed of water and collagen and has a gelatinous consistency. (Some people describe the disc structure as resembling a jelly donut.) The disc allows for movement of the vertebral bodies and provides a buffer for compression between the bones.

In a healthy disc, this system works very well. But degeneration of or injuries to the disc can lead to a lumbar disc herniation.

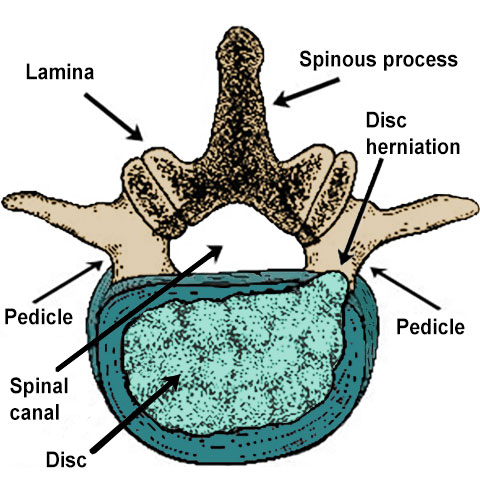

Overhead illustration of a lumbar spinal disc

- What is a lumbar disc herniation?

- What is a disc protrusion versus an extrusion?

- What are the symptoms of lumbar disc herniation?

- Why do I feel pain in my leg if the herniated disc is in my back?

- What is the treatment for lumbar disc herniation?

- When is surgery needed for lumbar disc herniation?

- What is the surgery for a lumbar herniated disc?

- What happens to my herniated disc if I don’t have surgery?

What is a lumbar disc herniation?

A herniated lumbar disc is a broad term to describe a change in a spinal disc of the lower back. A disc herniates when there is tear in its tough, outer, fibrocartilaginous layer (called the annulus fibrosus), allowing portions of its gelatinous, inner layer, the nucleus pulposus, to leak out through the tear. There are several different types of disc herniations. Herniations can be protrusions, extrusions, or sequestrations.

Overhead (top view) illustration of a lumbar vertebra with a herniated disc

What is a disc protrusion versus an extrusion?

There are different types of disc herniations, and they are described according to their size and how they look. Remember, a spinal disc rests between two vertebral bodies of bone and there is often a lot of pressure between these structures. A disc bulge is a normal age-related change to the disc where the outer part of the disc flattens. A disc protrusion is a type of disc herniation where the depth of the herniated disc material is shorter than how broad it is. A disc extrusion is where the depth of the herniated disc material is larger than how broad it is. A disc sequestration is where the herniated fragment or material is no longer connected with the disc.

What are the symptoms of lumbar disc herniation?

In some cases, herniations cause no symptoms whatsoever. When symptoms occur, the most common symptom from a lumbar disc herniation is lower back pain. If the disc herniation causes impingement of a nerve, for example, one of the nerves that make up the sciatic nerve, pain may also radiate down into the leg via the sciatic nerve (a condition known as sciatica). In addition to leg pain, the leg may also be weak or numb.

Overall, whenever a disc has herniated, it can cause various pain symptoms and additional, related conditions.

- The disc may become painful itself.

- It may irritate a nerve exiting the spinal column, leading to pain, weakness, numbness or tingling in the leg.

- It may even contribute to a narrowing of the spinal canal itself, also known as lumbar spinal stenosis, which often leads to pain, weakness, numbness or tingling in the leg.

What does it mean that my MRI report says I have multiple herniated discs?

What you feel in terms of pain or discomfort is more important than what the MRI report says, because it is quite common for spinal imaging to reveal that a person has multiple herniated spinal discs, even if they are experiencing no back pain. Therefore, the most important thing is not the MRI report itself, but rather correlating your symptoms and physical exam with the MRI report. If the MRI report indicates that a disc herniation is present, this could be significant or insignificant, depending on your symptoms and other factors.

Why do I feel pain in my leg if the herniated disc is in my back?

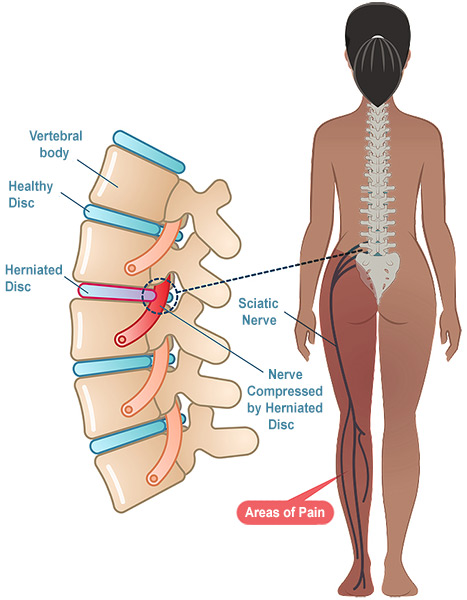

The lumbar disc sits between two vertebral bodies. Behind the vertebral bodies and discs lie the spinal cord and nerves. The nerves in your legs originate from the spinal cord and its nerve roots. The nerves run in the central spinal canal and then come out between two of the spinal vertebrae in a space called the foramen. When a disc herniates, it can impinge a nerve where it comes down in the central canal or where it comes out in the foramen which can then send pain down the leg.

When these nerves are still in the spinal canal, they are named in reference to the disc level they are located near. For instance, the L5 nerve comes down in the central canal at the L4-5 and above levels and then comes out in the foramen at the disc level between the L5 and S1 vertebral bodies. (S1 is the first vertebra of the sacral spine.) Once they exit the canal at the individual vertebrae levels, the nerves come together to make up named nerves, such as the sciatic nerve, which is made up of the L4, L5, S1, S2 and S3 nerves. Therefore, if any of these nerves are impinged up near the spinal column, patients can feel pain where the sciatic nerve is in the leg (a condition known as sciatica).

Illustration of a herniated disc causing sciatica.

What is the treatment for lumbar disc herniation?

There are a lot of options for treatment of a herniated disc in the lower back before considering surgery, including weight loss, a physical therapy program that may include recommendations for activity modification, pain medications, and/or epidural steroid injections.

Weight loss can help alleviate added pressure on the lower back and decrease the overall inflammation in a patient’s body, while a well-directed physical therapy program will allow for the disc to heal and provide improvements in biomechanics and strength. Pain medications can often be helpful. For instance, anti-inflammatory medications can be helpful to decrease the inflammation and muscle relaxers can be helpful to decrease the muscle spasms that occur as a result of a disc herniation. Often, physical therapy, with or without the benefit of pain medications, can allow a patient to feel better, improving a patient’s pain and functionality.

However, when the pain becomes too severe, specifically nerve pain felt in the leg from the disc herniation, and does not respond to physical therapy and medications, epidural steroid injections can be very helpful. Studies have shown excellent pain reduction and improvement in function with the use of epidural injections. Although epidural injections are safer than more invasive surgical procedures, there can be complications. These include new pain, worsening pain, bleeding, headaches, adverse reaction to the medication injected or, even more rarely, infections, or injury to a nerve.

For many patients, a combination of treatment options including medications, physical therapy, and epidural injections results in the best outcomes. (Find a doctor who treats herniated discs.)

What should I do if a herniated disc still hurts after a year?

Most herniated discs will resolve on their own, or their associated symptoms will be alleviated with conservative treatments. If the patient’s functionality is greatly impacted and they have not responded to activity modification and other conservative measures, it is reasonable to consult with a surgeon about spine surgery options.

Many times, symptoms from a disc herniation will be very short-lived and quickly resolve. However, symptoms from herniated discs can linger because we use our spine to differing extents with differing loads on the spine with everything we do throughout our day.

An analogy to consider is a scratch on the arm. With a scratch on the arm, a patient often bandages it and leaves it alone and, because of this, after a few days the scratch heals and sometimes scars. When a disc tears and herniates, the body tries to heal the disc, but we have to use our spine with everything we do throughout our day. Therefore, the healing process can become prolonged as the scab may at times be ripped open, and new tears can occur. Therefore, learning how to bend, lift and twist in the most optimal way for our spine is of utmost importance to help prevent reinjury.

Whether the disc is symptomatic for one day or one year, the conservative approach is the same as long as there is not progressive neurologic change. Activity modification is required so the disc is not reinjured and therapeutic exercise in the form of physical therapy is beneficial to work on strengthening around the spine and stability. Medications can be considered along with epidural injections if there is nerve pain secondary to the disc herniation.

Can a herniated disc heal after two years?

A herniated disc can at times “resorb” – where the body’s own cells come in and get rid of the damaged disc material. Regardless of whether the disc material that has herniated becomes resorbed, the tear in the outer portion of the disc can scar over and the herniated material can be contained in such a way that, over time, it ceases to cause pain, weakness, numbness or tingling. This healing process is facilitated by modifying movement and activity to use optimal mechanics for the spine – which is hopefully a part of any physical therapy program. Using the “scratch on the arm” analogy previously mentioned, if the scratch and scar are not repeatedly injured and irritated, then the disc can heal appropriately.

When is surgery needed for lumbar disc herniation?

There are some situations where surgery is probably the best solution. These include if you have cauda equina syndrome, progressive strength loss, intractable pain, or other continued symptoms despite trying nonsurgical treatments.

Cauda equina syndrome

Cauda equina syndrome is an extremely rare but serious disorder affecting a bundle of spinal nerve roots, and it requires urgent surgery. This syndrome involves back and leg pain, weakness and numbness, and may be associated with problems with bladder and bowel function. This condition usually arises only in the case of a severe lumbar disc herniation that severely decreases the space where the spinal nerves come down in the central canal.

Progressive strength loss

There are times when strength loss is noticed. However, if the patient has new or progressive weakness, this would be an indication for surgery.

Intractable pain and failure of conservative care

If pain cannot be controlled with medicines, injections, or physical therapy, or if a comprehensive program including all of these options has failed, you may be a candidate for surgery.

What is the surgery for a lumbar herniated disc?

Whether there is one or multiple herniated discs, various types of spinal decompression and spinal fusion surgeries are available to treat lumbar disc herniations. These include microdiscectomy, lumbar laminectomy or a lumbar interbody fusion. The choice of which procedure is appropriate depends on the condition and other factors in each individual patient. In some people who have an isolated disc herniation, a disc replacement surgery may be a viable alternative to fusion. Where possible, a minimally invasive approach is often preferred. Ultimately, the surgeon indicates and decides on the best surgical option with the patient’s safety and goals as the utmost priority in the decision-making process.

What happens to my herniated disc if I don’t have surgery?

A study of patients with different sized herniations showed that by six months to one year, herniated disc material had resorbed in many of the cases. The larger the herniation (extrusions), the faster the material was resorbed. Long-term studies have shown that, although surgical intervention may generate a faster initial recovery time, conservative (nonsurgical) outcomes are equally effective in patients after five and 10 years.

However, if progressive neurologic changes are occurring, it is advised to consult with both a non-operative spine specialist and with a surgeon, who may best determine together the best path forward. For instance, weakness can improve on its own, however, the longer you wait to intervene from a surgical standpoint, the less likely it is that neurologic recovery will be seen. Furthermore, cauda equina syndrome is a surgical emergency to prevent loss of bladder and bowel function along with worsening weakness, numbness and tingling.

Updated: 3/17/2023

Authors

Attending Physiatrist, Hospital for Special Surgery

Assistant Professor, Clinical Rehabilitation Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College

Related articles

Success Stories

References

- Birkmeyer NJ, Weinstein JN: Medical versus surgical treatment for low back pain: evidence and clinical practice. Eff Clin Pract. 1999 Sep-Oct;25:218-27.

- Boden SD, Davis DO, Dina TS, Patronas NJ, Wiesel SW: Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990 Mar;723:403-8.

- Brant-Zawadzki MN, Jensen MC, Obuchowski N, Ross JS, Modic MT: Interobserver and intraobserver variability in interpretation of lumbar disc abnormalities. A comparison of two nomenclatures. Spine. 1995 Jun 1;2011:1257-63; discussion 1264.

- Fritz, Julie M. PhD, PT, ATC *; Delitto, Anthony PhD, PT, FAPTA *+; Erhard, Richard E. DC, PT: Comparison of Classification-Based Physical Therapy With Therapy Based on Clinical Practice Guidelines for Patients with Acute Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Spine. 2813:1363-1371, July 1, 2003.

- Huston CW, Slipman CW, Garvin C: Complications and side effects of cervical and lumbosacral selective nerve root injections. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005 Feb;862:277-83.

- Lutz GE, Vad VB, Wisneski RJ: Fluoroscopic transforaminal lumbar epidural steroids: an outcome study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998 Nov;7911:1362-6.

- Ohnmeiss DD, Vanharanta H, Ekholm J:Degree of disc disruption and lower extremity pain. Spine. 1997 Jul 15;2214:1600-5.

- Saal JA, Saal JS, Herzog RJ: The natural history of lumbar intervertebral disc extrusions treated nonoperatively. Spine. 1990 Jul;157:683-6.

- Spencer DL: The anatomical basis of sciatica secondary to herniated lumbar disc: a review. Neurol Res. 1999;21 Suppl 1:S33-6. Review.

- Vad, Vijay B. MD; Bhat, Atul L. MD ,[S]; Lutz, Gregory E. MD; Cammisa, Frank MD:Transforaminal Epidural Steroid Injections in Lumbosacral Radiculopathy: A Prospective Randomized Study. Spine. 271:11-15, January 1, 2002.

- Weber H: The natural history of disc herniation and the influence of intervention. Spine. 1994 Oct 1;1919:2234-8; discussion 2233. Review.

- Weinstein SM, Herring SA: Lumbar Epidural Injections, Spine J. 2003 May-Jun;33 Suppl:37S-44S.