Distal Radius Fracture: Diagnosis, Treatment and Recovery

While commonly referred to as a “broken wrist,” most wrist fractures are actually fractures of one or both of the two bones of the forearm, the radius and the ulna. A fracture of the distal radius is one of the most common types of injuries to the skeletal system. It is treated using a variety of different techniques, from casting to pinning to open surgery with plates and screws.

What is a distal radius fracture?

This is a break in the radius bone, the larger of the two bones in the forearm that connect the hand to the elbow. Its unique design facilitates wrist motion and forearm rotation. The end of the bone closest to the hand, the distal radius, is especially susceptible to breaking, because it composes approximately 80% of the wrist joint surface and is subjected to extreme load when people fall on their outstretched hands (FOOSH).

What are the different types of distal radius fracture?

There are a wide variety of fracture patterns, and no single form of treatment applies for all of these fractures. The nature and location of this fracture, compounded by the multidirectional forces we exert on this joint in our daily lives, often requires surgery to achieve proper healing, restore anatomic alignment of this important bone, and function of the wrist joint. There are two common variants of distal radius fractures that are characterized by the direction of forces applied to the wrist during a fall:

- Colles fractures are the most common type of distal radius fracture, and occur when falling on an outstretched hand, where the hand is extended backward on the forearm.

- Smith fractures, which is usually caused by the opposite mechanism, that is, when the hand is flexed forward under the forearm.

Either direction of fracture has a worse prognosis if it involves the joint surface (articular fracture), as this introduces the possibility of cartilage damage and ultimately, arthritis. Many other fracture types exist in addition to these two most common types. Available treatment options depend on the type and severity of the fracture as well as the needs, health, and activity level of the injured patient, and these options need to be carefully individualized by the treating physician to achieve a satisfactory functional outcome.

In general, the least invasive treatment – provided it achieves our goals of satisfactory alignment and stable reduction of the fractured bone fragments – results in a better functional outcome and patient satisfaction.

Navigating a patient through a particular treatment plan is a complex task and requires consideration of multiple factors and close attention during the healing phase.

Classifications of distal radius fractures

Dozens of classification systems have been proposed to identify the many different patterns of distal radius fractures, and are generally based on the number of fragments, the involved joint surfaces, and amount of fragment displacement. Distal radius fractures are increasingly classified by specialists according to the mechanism of injury that caused the break.

Five distinct fracture patterns have been described by D.L. Fernandez, MD, based on the direction and degree of force applied to the radius in the fall:

- Bending

- Shear or osteochondral

- Compression

- Fracture-dislocation

- Complex

Bending fractures of the distal radius – Colles and Smith

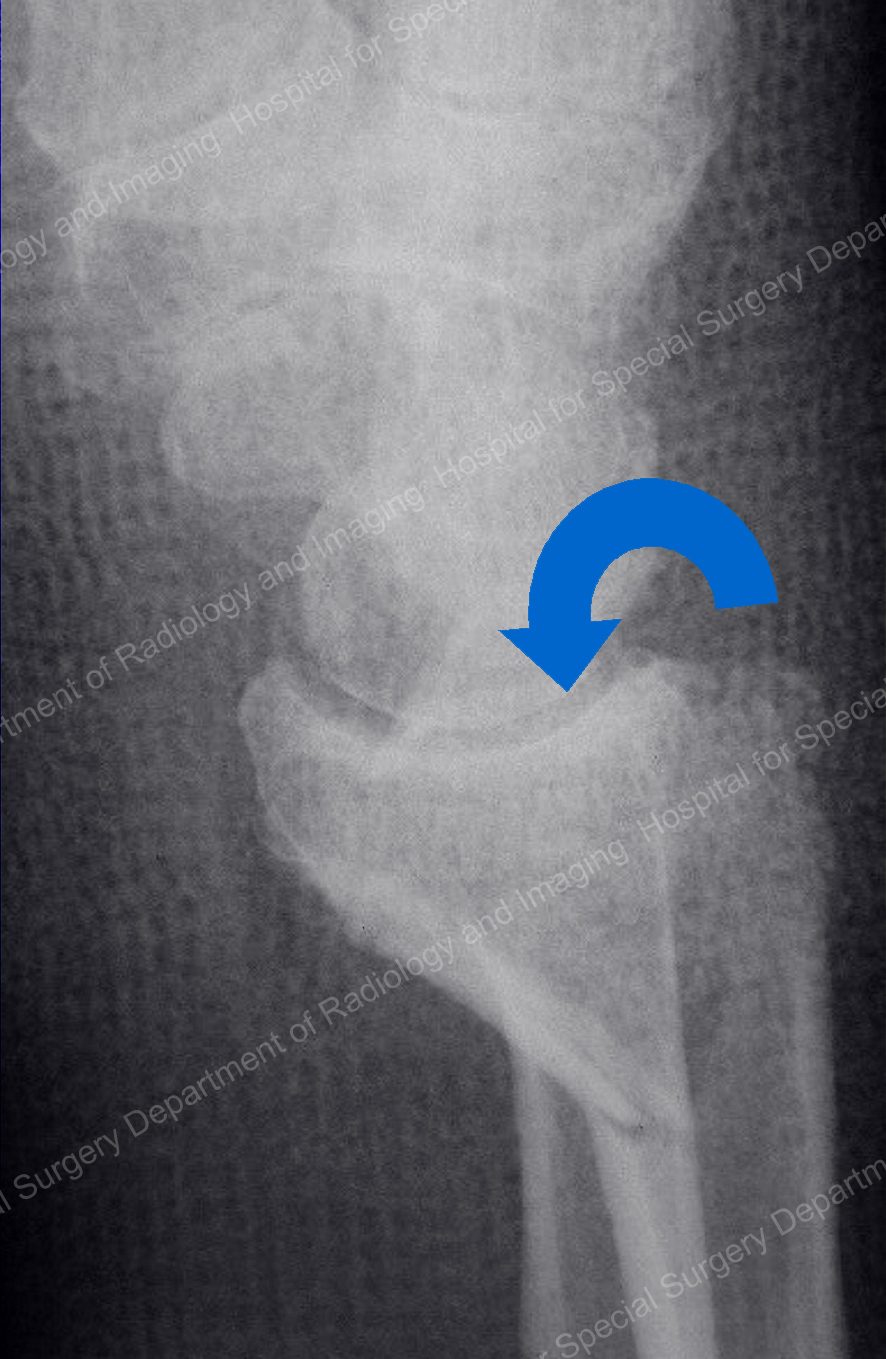

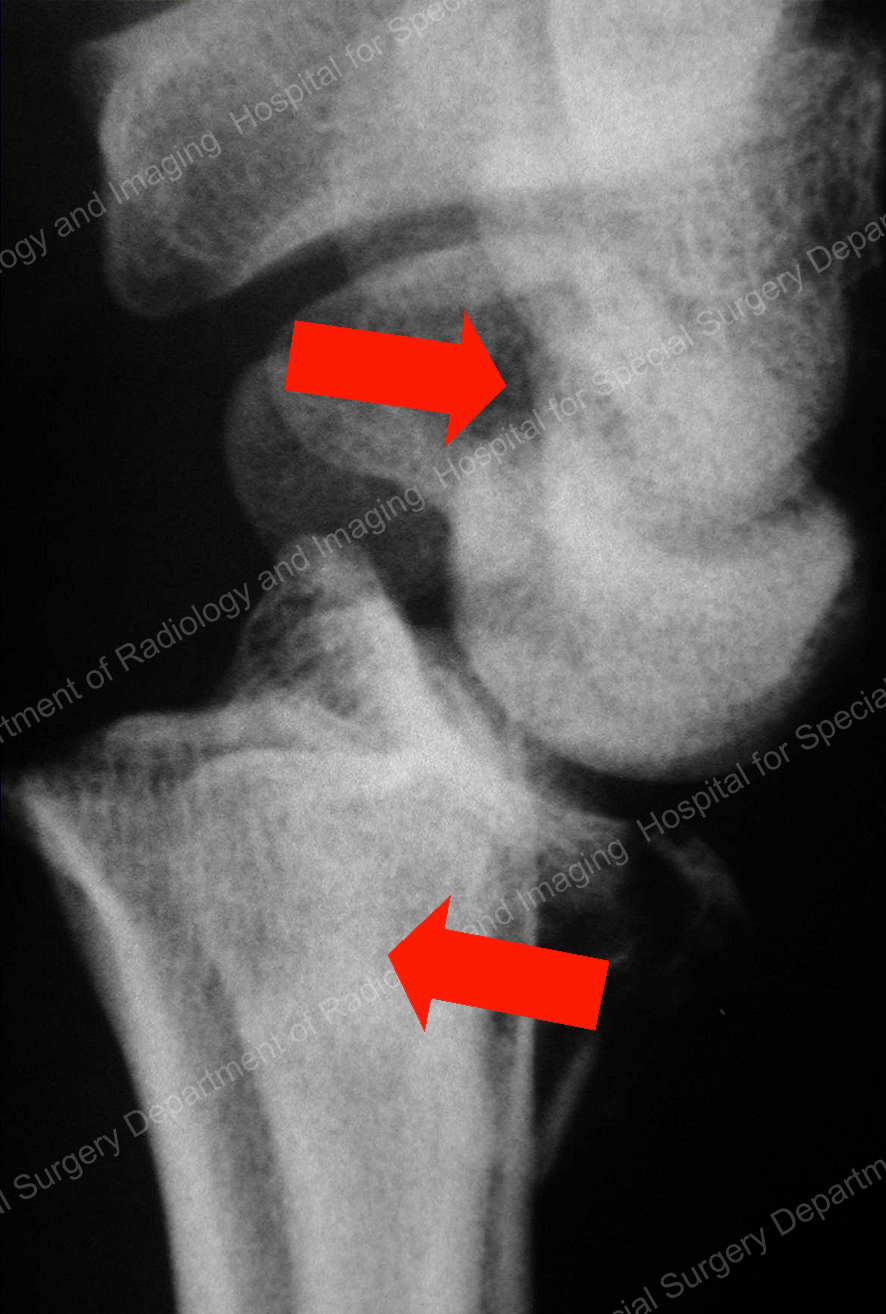

While Colles (dorsal) fractures are caused by a "bending" of the bone when the hand is extended backward on the wrist, (see Figure 1). Smith (volar) fractures are caused by "bending" in the opposite direction, with the hand flexed forward under the wrist (see Figure 2).

Figure 1. A Colles fracture of the distal radius

Figure 2. A Smith fracture of the distal radius

Shear fractures of the distal radius

Also known as an osteochondral fracture, "shear" refers to the action of the bone and its movement as the result of the fracture. As the fracture occurs, the bone shears – one end of the bone moves in one direction while the other moves in the opposite direction, similar to the way a road or highway may be sheared by an earthquake.

In an osteochondral" fracture (see Figure 3), the entire joint cartilage is sheared from the end of the radius with its underlying support bone, leaving the shaft of the bone intact. This is a highly unstable fracture, and treatment is difficult because of the small size of the fractured fragments and attached joint cartilage.

Figure 3. Shearing of the distal radius, known as an osteochondral fracture

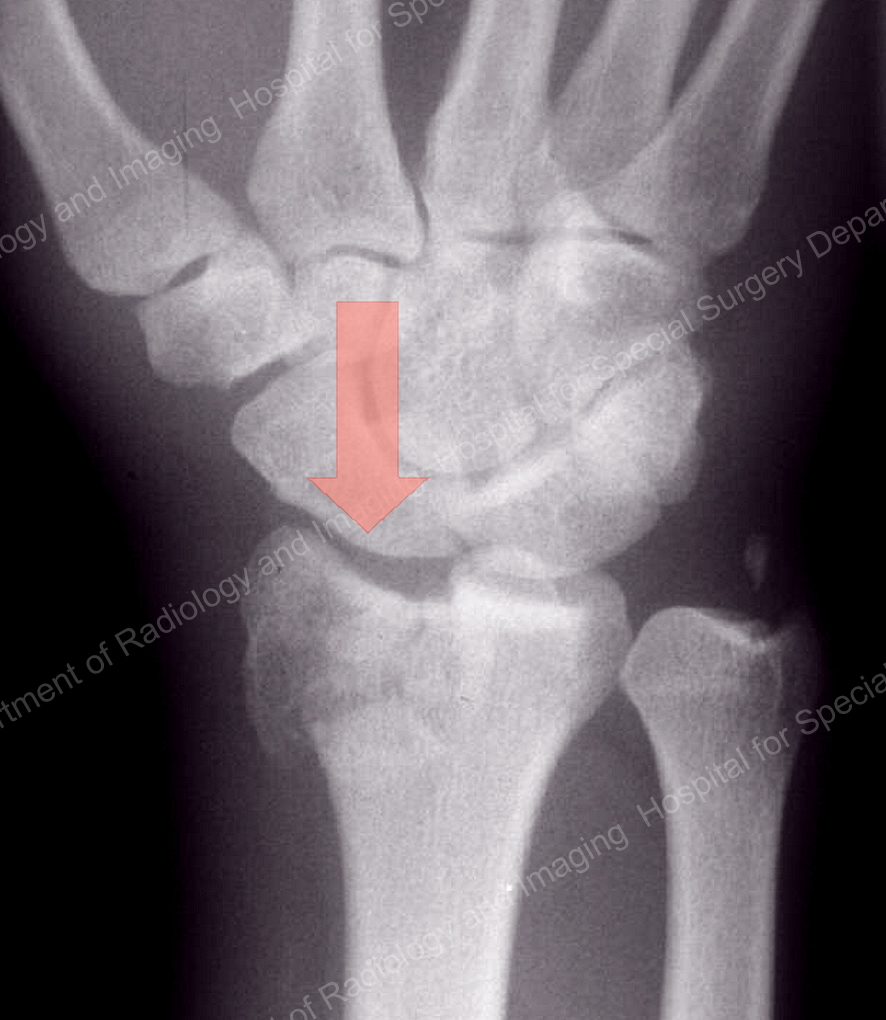

Compression fractures of the distal radius

In falls from a height or other high energy injuries, the hand and wrist bones can be compressed against the flat surface of the distal radius, which yields under the tremendous, applied load.

This compressive injury impacts the smaller wrist (carpal) bones into the joint surface of the radius, altering the lattice framework of the inside of the bone and smashing fragments of joint surface into the radius itself.

Figure 4. Compression fracture of the distal radius

Fracture-dislocations of the distal radius

In this high-energy injury, the carpal bones are dislocated from the end of the radius. Along with injury to the supporting ligaments of the wrist, this may result in fragmentation of a portion or all of the joint surface.

Outcome of these injuries depends not only on reconstituting the integrity of the joint surface, but on repair and remodeling of the injured wrist ligaments.

Figure 5. Fracture-dislocation of the distal radius

Complex fractures of the distal radius

This is a catastrophic injury, with extensive damage to the joint surface, fragmentation of the widened flare (metaphysis) of the distal radius, and damage to the shaft of the radius and/or the neighboring ulna. Often, these combination injuries require a combination of treatments to successfully reconstruct the damaged elements.

Figure 6. Complex fracture of the distal radius

How is a distal radius fracture diagnosed?

Workup of a distal radius fracture: A proper diagnosis begins with proper imaging, including initial X-rays and possible advanced 3D imaging. Computed tomography (CT) may be employed on occasion to assess the alignment or fragmentation of the joint surface and, less frequently, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be required to rule out concurrent injuries to ligaments or injuries to other bones in the wrist, such as the scaphoid.

It is now our practice to recommend to all women over the age of 50 who experience a fracture of the distal radius to consider getting a bone density test (DEXA scan) to assess for the presence of osteoporosis. We also recommend that patients of all ages have a vitamin D level to assess their ability to heal their fracture.

A fracture that is displaced, meaning the fracture fragments are out of normal alignment, will require a "reduction," which refers to an attempt to manipulate the fracture fragments back into alignment, followed by splinting of the fracture in a below-elbow or above-elbow plaster brace. Following the reduction, new X-ray images will be performed in plaster to assess alignment. If the reduction is deemed acceptable, periodic images will be taken during the healing period to ensure that the position or alignment of the fracture fragments does not change.

Fractures that are felt to be unstable – due to osteoporotic bone or extensive fragmentation – may be vulnerable to "settling" or loss of reduction, and follow-up imaging may be necessitated as often as every week. More stable fractures may require less frequent follow-up X-rays over the 6 to 8 weeks required for healing.

If the fracture cannot be reduced within an acceptable degree of alignment, or it is deemed grossly unstable and likely to re-displace in plaster immobilization, the physician may recommend surgery to reduce and stabilize the fractured fragments under anesthesia.

How are distal radius fractures treated?

As above, initial “urgent care” or emergency department treatment involves a reduction under local anesthesia followed by temporary splinting and outpatient care with an orthopedic hand or trauma surgeon. Stable fractures can generally be treated nonsurgically with casting for approximately six weeks. Unstable and/or displaced fractures in young and active individuals are often managed with surgery to align the fracture fragments and joint surfaces in order to optimize outcomes and a patient’s return to function.

Closed reduction

Using various forms of anesthesia to minimize discomfort, the physician manipulates the fracture fragments into proper alignment (reduces the fracture) without making an incision or directly exposing the fracture.

A plaster splint or cast is applied and molded to the patient’s forearm and hand. Often, the plaster may extend above the elbow to help provide additional stability and neutralize the extensive forces that can be generated by natural movements of the arm and forearm.

Following closed reduction, subsequent treatment will be recommended based on an array of patient-related and radiographic factors. The condition and needs of the patient are of paramount importance when considering treatment options, and include the patient’s general medical status, activity level, age, and bone quality.

If a patient’s medical condition permits, the goals of treatment are relatively straightforward: restoration of bony alignment, attainment of smooth joint surfaces, and provision of stability until healing.

After determining the mechanism and type of distal radius fracture, its stability can be predicted to some extent based on five important factors. These are the:

- degree of fragmentation of the bone

- amount of displacement that occurred at the time of injury

- integrity of the three columns of the wrist, including the ulna bone

- age of the patient (a relative barometer for osteoporosis)

- integrity of the joint surface

After considering these factors, as well as the general health and needs of the patient, a surgeon will decide whether a fracture is likely to be stable or unstable following closed reduction, and will recommend one or more of the following treatment options:

Casting

Casting provides external stability to the forearm and hand by the application of gentle pressure to the skin and underlying soft tissues. This provides a rigid mold and contains the reduction in proper alignment during the healing period. If the fracture is stable and has been successfully realigned by the reduction, casting may be the only treatment necessary.

Casts will need to be removed and replaced several times during the healing period to insure snug and secure support of the fracture. Casts may be applied either "above elbow" or "below elbow" and may include the thumb or not, depending on the particular type of injury and physician preference.

Casts are generally made from plaster early in the treatment, which allows for some degree of swelling, and the more rigid and lighter-weight fiberglass material during later stages of healing.

Figure 7. Casting for a stable distal radius fracture

Surgery

When surgery is necessary, there is usually a two-week window of opportunity before early bone healing begins. This interval may be a good time to seek a second opinion to explore your options. The additional time until surgery does not affect ultimate outcome.

When one considers the gravity of the injury, its immediate and potential long-term impact on one’s activities and livelihood, the amount of ongoing research, and the number of recent changes in treatment of these injuries, it is important to get a thorough understanding of the treatment options, expected outcomes, and potential complications of treatment.

Types of fixation for distal radius fracture wrist surgery

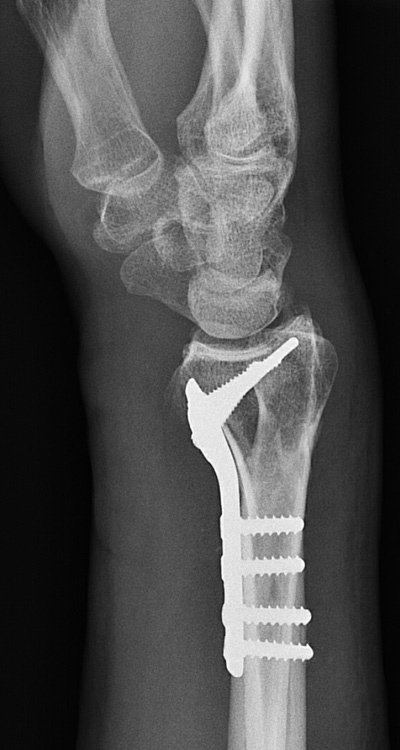

Internal fixation (plates, screws, pins)

A common surgical option is ORIF (open reduction and internal fixation), in which an incision is made over the fracture on the palm side of the forearm, and internal fixation (a stainless steel or titanium plate with screws) is placed to align the bone ends and prevent displacement or loss of reduction.

Figure 8a. Internal fixation of a distal radius fracture with a volar angular stable (locked) plate

Figure 8b. More severe fractures may warrant several smaller implants to achieve fragment-specific fixation.

Advantages of internal fixation include:

- increased stability of fracture fixation

- the ability to begin moving the wrist and using the hand shortly after surgery

- strategic placement of implants for small fracture fragments

- the lack of a need for an external device or protruding pins

- less obtrusive casting, decreased stiffness and atrophy

This may not be suitable for all fractures – possible complications of this technique include:

- loss of fixation

- improper positioning of the plate or screws

- infection

- the need for hardware removal

- nerve injury

- tendon injury or rupture

- stiffness

- complex regional pain syndrome

Percutaneous fixation with pins and casting

Some types of fractures, while unstable in a cast alone, require only the addition of one or more pins to create a stable situation and enable treatment with a cast. The pins can be placed without the need for an incision and are done in the operating room under a regional anesthetic. The wrist is then placed in a cast until healing, at which time the pins are removed and therapy begun.

Advantages of percutaneous pin fixation include:

- adequate stability for closed treatment

- no need for permanent hardware implantation

- minimal soft tissue or bony complications

- less painful procedure

- minimal scarring and no surgical incision

This may not be suitable for all fractures – possible complications of this technique include:

- loss of fixation

- settling / loss of reduction

- pin infection

- re-operation

- nerve injury

- tendon injury

- stiffness

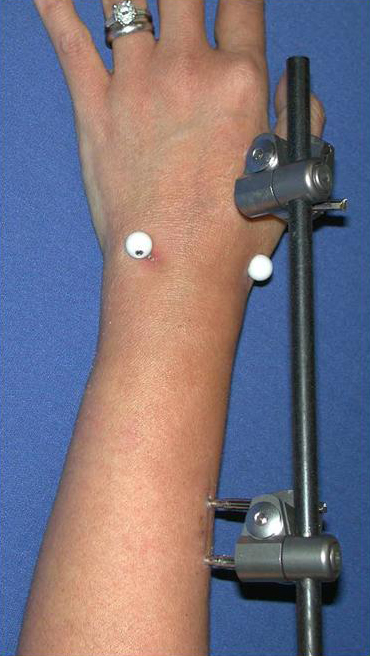

External fixation

External fixation is a time-honored technique that involves using an external frame holding pins placed in the bone through small incisions on both sides of the fracture.

External fixation, generally augment by percutaneous pin fixation, was the predominant mode of treatment in the 80’s and 90’s, and had excellent outcomes. It has largely been supplanted by internal fixation, following the advent of angular stable volar plate and fragment-specific fixation.

Figure 9. Example of external (percutaneous) fixator for distal radius fracture.

Advantages of external fixation include:

- a proven, time-honored technique

- minimal soft tissue disruption/minimally invasive

- all hardware is removed (no concerns for airport security or tissue response)

- skin incisions result in minimal scarring

- bone graft may be used to support the joint surface

- equivalent or improved clinical, radiographic, and functional outcomes in selected fractures

Disadvantages of external fixation include:

- the visible presence of a bulky metal or plastic frame

- protrusion of pins from the skin surface and possibility of pin tract infection

- inability to begin moving the wrist joint for several weeks after surgery

Possible complications include:

- wrist and hand stiffness

- pin tract infection

- nerve injury

- settling/loss of reduction

- a need for reoperation (a second surgery)

- over-distraction and complex regional pain syndrome

What is the recovery time for distal radius fracture surgery?

Most fractures are healed sufficiently to begin light active use of the hand by six weeks, but this will vary depending on the severity of the injury, metabolic and systemic conditions, and whether surgery was performed.

Cast treatment recovery

The rule for fracture healing is to expect a six-week period to ensure sufficient bone strength. It is generally advised to include an additional week or two of support in a removable plastic splint. A stable fracture may be treated with a combination of casting and splinting throughout this healing period.

Internal fixation recovery

In most cases, a patient who has undergone internal fixation surgery for a distal radius fracture may begin gentle wrist range of motion within 1 to 2 weeks of surgery, after which time a removable splint is used to support the hand.

The hardware that was surgically placed inside the arm/wrist at the time of surgery may be left in place indefinitely. Approximately 5% of implants are ultimately removed.

An individualized treatment plan for distal radius fractures

Fractures of the distal radius are very common and modern treatment methods of casting or internal fixation lead to excellent outcomes in most cases. Given the wide variety of fracture types, there is no one treatment that is effective for all fractures Each fracture requires carefully considered treatment that is customized to repair the specific fracture characteristics and meet the occupational and recreational needs of the patient.

An important consideration when treating a fracture of the distal radius is to assess its “personality” and customize one’s treatment to best match its personality. As I am fond of saying, “It’s the archer, not the arrow.”

Updated: 11/19/2024

Authors

Attending Orthopedic Surgeon and Senior Scientist, Hospital for Special Surgery

Professor of Orthopedic Surgery, Wrist Surgery and Nerve Repair, Weill Cornell Medical College