Options for Treating Early Inflammatory Arthritis

The management of inflammatory arthritis has moved to a completely different plane than 30 years ago. The literature provides clear evidence of the benefits of treating early inflammatory arthritis preemptively. In addition, with the availability of biologic agents for rheumatoid arthritis since 1998, our therapeutic options are dramatically improved, and our choices expanded. The focus of this article is to examine the active, aggressive management of rheumatoid arthritis. Of special concern is the ability of early treatment to prevent joint damage and ultimate disability.

Overview of Rheumatoid Arthritis

Several features of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), one of the most common of the inflammatory types of arthritis, make it a major health issue for individuals and for society. It is fortunate that there have been major improvements in our therapeutic options.

Rheumatoid arthritis is:

- Common

- Painful

- Deforming and disabling with cardiovascular and many other comorbidities

- Life-shortening (without successful treatment)

- Costly to individuals and society

- Very successfully treated in the vast majority of cases

The following is an example of a typical patient who would be diagnosed with early RA, a patient with antibodies suggesting a worse prognosis than for patients who are serologically negative:

- 38-year-old woman previously well

- 3 months swelling of hands, wrists, knees and ankles

- 2.5 hours morning stiffness

- Afternoon fatigue

- ESR 78, Rheumatoid factor 1:160, anti-CCP antibody strongly positive

- Normal X-rays

Treatment Options for Rheumatoid Arthritis

Principles of treatment:

- Joint damage appears early

- DMARDs (disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs) can alter the clinical picture and decrease erosion of bones and improve long-term function and appear likely to lengthen life and reduce comorbidities (such as impacting the increased cardiac risk of patients with RA)

- Assessing prognosis is key to selection of appropriate treatments

- Regular follow-up needed to make sure patient is reaching appropriate goals of disease improvement (treat to target)

Because joint damage often occurs early in rheumatoid arthritis, medications that can stop that damage are crucial. Identifying those patients at higher risk for later disability is key to making the right therapeutic decisions.

Noninvasive treatment options:

- Formal physical therapy, with various modalities

- Home exercise

- Local heat/ice

- Massage

- Paraffin baths for hands

- Splinting (e.g., wrists)

These noninvasive treatment options for rheumatoid arthritis need to be individualized to the patient, but all patients with rheumatoid arthritis benefit from at least some physical therapy and from learning proper exercise techniques to do at home. Some patients are greatly helped, for example, by wrist splints or by paraffin bath therapy for the hands.

Medications for Rheumatoid Arthritis

In the present era, all patients with rheumatoid arthritis benefit from medications of some type, and often require a combination of medications. Analgesics such as acetaminophen are very commonly used by patients with RA. The vast majority of patients with RA end up requiring DMARDs (disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, also called “slow acting agents”) and many benefit from having such agents started quite early in their course.

Spectrum of pharmacotherapy for rheumatoid arthritis:

- NSAIDs

- Analgesics: e.g., acetaminophen

- Corticosteroids such as prednisone and methylprednisolone

- Disease-modifying agents (DMARDs): hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine, methotrexate, leflunomide

- Biologic agents

- JAK inhibitors: e.g., tofacitinib

NSAIDs

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs) make a big difference in daily function for some patients with RA, especially until their long-acting agents can take effect. However, we know that patients with RA are at higher risk of atherosclerotic heart disease, making it more problematic to use long-term high-dose nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. Also, RA is associated with a higher-than-average risk of peptic ulcer disease, even without the use of NSAIDs. NSAIDs also can raise blood pressure and cause fluid retention. Considering all this, the ideal is to use NSAIDs (and the COX-2 inhibitor celecoxib) at the lowest dose and for the shortest time possible. The multiple disease-modifying treatments available for RA often make this possible. However, some patients need to try a number of long-term treatments before they get their arthritis under control, and in such patients the use of NSAIDs, in full therapeutic doses, may be needed for a longer period to allow them to function.

In summary, NSAIDs are:

- Still used in many RA patients

- Of increased risk in RA patients due to their higher cardiovascular risk

- Of increased risk in RA patients due to higher ulcer risk at baseline (and the cardiovascular prophylactic aspirin used by many patients with RA may further increase ulcer risk)

- Apparently safer if used topically, e.g., diclofenac gel and patches, which appear to have significantly decreased risk compared to oral use

Analgesics

Analgesics for prn use are used in many RA patients and can be important to get them through times of significant pain. While it is desirable to control RA with medications that not only stop pain but also help prevent joint damage, a role for analgesics is clearly present in this disease. They may be additive to NSAIDs or replace them.

Acetaminophen is commonly used, and some patients benefit from topical lidocaine patches or roll-on applications. In some cases, narcotic pain medication is needed, e.g., tramadol, but present efforts aim to use the smallest doses for the shortest possible period of time to reduce side effects and habituation. Fortunately, our ever-improving armamentarium for treating RA has made analgesics much less of an issue than in the past.

Corticosteroids

- Probably don’t have a disease-modifying effect (reduction in erosion), but this is debated

- Often used as a "bridge" while awaiting DMARD effect

- Used for major flares

- Low-dose an alternative to NSAIDs (e.g., 5 to 7.5mg qd)

Types:

- Intra-articular

- IV

- Intra-muscular

- Oral

Corticosteroids continue to be used in managing inflammatory arthritis. Their side effects are very dose-related, and below 7.5mg daily of prednisone, it appears that there is not a major effect on bone density (still some debate about this). Certainly corticosteroids are often used while waiting for long-acting agents to work, and they are often used in fairly high – but brief – courses for major flares. The literature remains controversial as to whether corticosteroids are “disease modifying” in the sense of being able to decrease joint erosion. Use of corticosteroids in RA needs to be highly individualized in view of the potential for toxicity.

Slow-acting Agents

Slow-acting agents for rheumatoid arthritis have been the mainstay of management of RA for many years. Their combination with, and at times replacement by, biologic agents is a new development starting in 1998 with the introduction of etanercept. Not all “slow acting” agents have been shown to be “disease modifying” – if that term is defined as “slowing or stopping joint damage.” The agents marked with three stars (***) are DMARDs in the sense that there is literature support for their ability to decrease joint damage (as demonstrated on serial X-ray review).

- Azathioprine Imuran®***

- Atabrine

- Cyclophosphamide Cytoxan®***

- Cyclosporine***

- Gold-injected***

- Hydroxychloroquine

- Leflunomide Arava®***

- Methotrexate***

- Minocycline

- Sulfasalazine Azulfidine®***

Hydroxychloroquine continues to be used in RA in view of documented clinical benefit and relatively low toxicity. It has not been demonstrated to slow joint damage. If doses are kept below 6mg/kg/day, the risk of retinal toxicity has shown to be low, especially in the first 5 years of use.

Hydroxychloroquine-Plaquenil®:

- Still used, usually in milder cases

- Dose: 6mg/kg/d – often 300 to 400mg qd

- Part of some combination regimens (e.g., with methotrexate and sulfasalazine)

- No evidence for disease modification

- Retinal toxicity rare but requires follow-up especially after 5 years

- Toxicity: Diarrhea and skin rash

Sulfasalazine Azulfidine®:

- Dose: 500mg enteric-coated tab, 4 to 6 daily, starting at one a day and adding 1 tab each week

- No infection risk unless induces leukopenia

- Sulfa-type allergy risk

- Severe leukopenia possible in first 3 months

- Used in some combination regimens

There is some evidence that sulfasalazine can decrease joint damage over time. The WBC count needs to be closely followed for the first 3 months after starting therapy with sulfasalazine since acute drops in WBC have been reported. Combination regimens with sulfasalazine, methotrexate, and hydroxychloroquine (“triple therapy”) have been described as effective in RA.

Older Agents

Azathioprine and cyclosporine have had disease modification demonstrated, but they are used less, and often after other agents, in view of toxicity. Their use has dropped dramatically after the introduction of the biologic agents. Penicillamine was commonly used 25 years ago, but toxicity has essentially removed it from standard usage for RA. Minocycline can help the symptoms of RA but has not been demonstrated to slow the destructive process.

- Some benefit but relatively high toxicity

- Azathioprine – used at times (up to 2.5mg/kg/d

- Cyclosporine – still used at time (2 to 5mg/kg/d)

- Penicillamine – almost never used

- Minocycline – mild effectiveness, well tolerated (50 to 100mg bid), not disease-modifying

Methotrexate is the most commonly used long-term agent for RA and is also the most common agent used in combination with other agents, such as the biologics.

- Most common first line agent – p.o. or s.c. once a week. Usually start orally 7.5mg to 15mg q week, increase over 6 to 8 weeks, to 15mg to 20mg q week. Can increase high as 25mg/week. Some have suggested splitting the dose of methotrexate by 12 hours on the day it is given once the dose exceeds 15mg per week, since absorption decreases over this dose and divided doses lead to higher blood levels. Alternatively, subcutaneous methotrexate can be used, which improves bioavailability and may help decrease GI side effects, but cost is a factor.

- Methotrexate has been documented to decrease erosion of bone

- Often the "anchor" in combination therapy

- Liver/lung/GI toxicity

Although liver toxicity has been demonstrated, when given in once a week 7.5 to 25mg per week regimen, the risk has been relatively small. Follow-up of liver function tests has been recommended in published guidelines to be done at approximately 5 week intervals, and this is still recommended early in therapy, but with time on the medication lab testing can be spaced out. An acute lung toxicity of an apparently allergic type can occur with significant dyspnea and requiring corticosteroid therapy, but fortunately this is rare.

Leflunomide: Arava® has also been shown to slow damage in RA joints. Leflunomide has liver toxicity risk, as does methotrexate, and requires close laboratory follow-up. Leflunomide has a long half life, and patients with side effects with this agent at times need a “wash out” process, involving large doses of cholestyramine to remove it via its enterohepatic circulation.

Biologic Therapy in RA

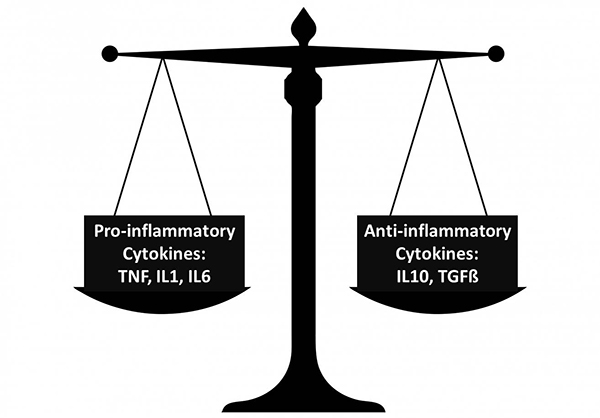

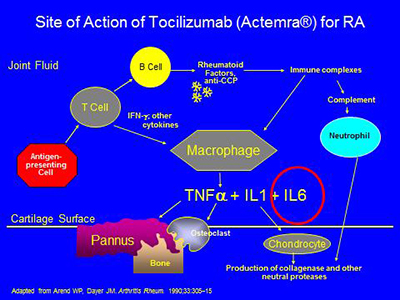

The inflammatory process in RA and other types of inflammatory arthritis can be thought of as a tipping of the cytokine balance in favor of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Among the most important pro-inflammatory cytokines in the RA joint appear to be TNF-alpha, IL-1, and IL-6. Each of these cytokines presently has at least one approved biologic agent capable of blocking it.

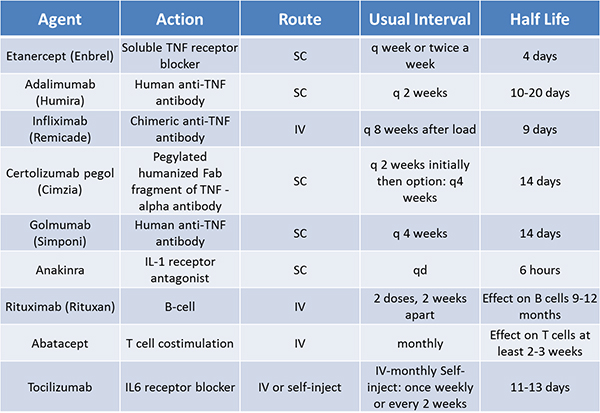

It is worthwhile to be aware of how long each of the biologic agents has been available in the US. Patients are especially concerned with medication for which there is short-duration clinical experience. We now have two decades of clinical experience with etanercept, the first biologic approved for RA (in 1998) (in addition to the studies done prior to this medication’s release). Multiple TNF-blocking agents are now available, in both subcutaneous and intravenous formulations.

The intervals of treatment are different for these agents: etanercept once a week, adalimumab once every two weeks, and infliximab is infused, after a loading period, once every two months. Certolizumab is given once every two weeks subcutaneously, and the interval can be subsequently extended to every four weeks. Golimumab is given once every four weeks, subcutaneously, and also has an intravenous formulation. These intervals are changed, at times, with some of these agents, related to patient response.

FDA-approved Biologic Agents

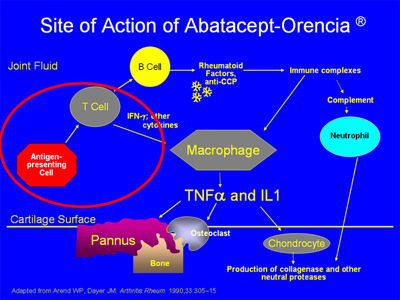

For the FDA-approved drugs with other mechanisms (see below), anakinra is given subcutaneously daily, rituximab at approximately six month intervals intravenously, and abatacept at one month intervals intravenously after a one month loading period during which an additional dose is given. Abatacept can also be given subcutaneously once a week. Tocilizumab is a blocker of the receptor for IL-6, and is given once a month intravenously or once every other week or once a week by self-injection subcutaneously. Rituximab binds to the CD20 antigen on the surface of B cells and leads to B cell depletion. It has been demonstrated to decrease clinical activity in RA in combination with methotrexate.

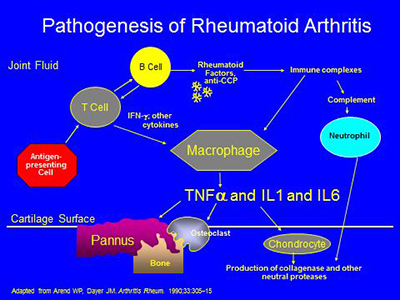

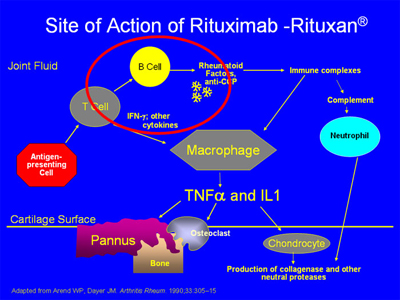

The pathogenesis of RA is complex, involving activation of T- and B-cells, antibody production, immune complex generation, complement activation, osteoclast activation, cytokine formation and the formation of locally erosive pannus on the surface of cartilage. Antibodies such as rheumatoid factor and anti-CCP (anticyclic citrullinated protein) are present in RA. Rheumatoid factor has not been proven directly pathogenic, but there is evidence that the CCP antibody may have such a direct role. Immune complexes containing rheumatoid factor circulate in RA. A schematic of some of the pathophysiologic processes in RA is below:

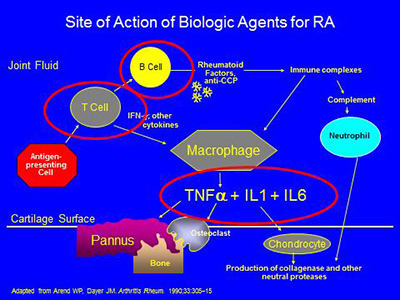

The biologic agents presently available work in the areas circled below – by blocking the effects of either TNF-alpha,IL-1, IL-6, or the activation of T or B cells:

Etanercept was the first biologic agent approved for RA and is given by self-injection most commonly once a week. It is also approved for use in psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. It is a soluble TNF-receptor which binds and inactives TNF alpha. The combination of etanercept with methotrexate has been shown to be more effective in producing clinical response and decreasing joint damage than either agent alone, but etanercept can be used alone.

Infliximab was the second biologic agent approved for RA. This agent is given intravenously. There is extensive worldwide experience with this agent, since it has been used for Crohn’s disease in addition to RA. It is also used for psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Infliximab is recommended to be given combined with methotrexate. It is a chimeric mouse/human monoclonal anti-TNF antibody which binds soluble and cell-surface TNF. It was approved in November 1999.

Adalimumab was approved for RA in 2002 and is also approved for use in psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Patients inject themselves once every two weeks. Like etanercept and infliximab, adalimumab is more effective when combined with methotrexate, but can be used alone. It is a monoclonal antibody to TNF, and was approved by the FDA in 2002.

Anakinra is the only IL-1 blocker presently approved by the FDA for use in RA. It requires daily self-injection, and local reactions are a problem for some patients. It seems somewhat less potent than the anti-TNF agents for RA, but seems less likely to cause infections as a side effect. It is an antagonist to the IL1-receptor (being a recombinant form of the naturally occurring IL-1 receptor antagonist). Dosing is 100mg daily. It was FDA approved in November 2001.

The anti-CD20 agent rituximab has a depleting effect on B cells but not on plasma cells. It has been demonstrated to decrease clinical activity in RA in combination with methotrexate. Its site of action is as noted below:

Abatacept works by decreasing the activation of T cells. Antigen-presenting cells activate T cells in a process which is key to the RA process (see area circled in red below):

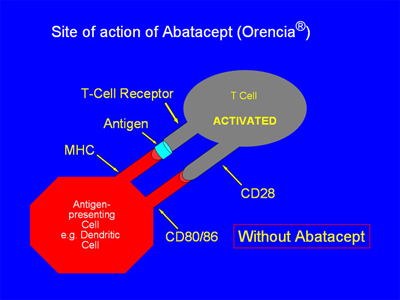

This T-cell activation occurs early in the chain of events that ultimately contributes to the cytokine-driven joint damage that is the hallmark of RA. Two signals are required for the activation of T-cells, and abatacept acts by By blocking the “second signal.”

In the absence of abatacept, as in the figure below, the antigen-presenting cell (APC) is able to give “2 signals” of activation to the T cell. First, the MHC on the APC and the T-cell receptor become linked via antigen binding. Second, the CD 80/86 receptor on the APC binds with the CD28 receptor on the T cell. With both signals completed, the T-cell is activated:

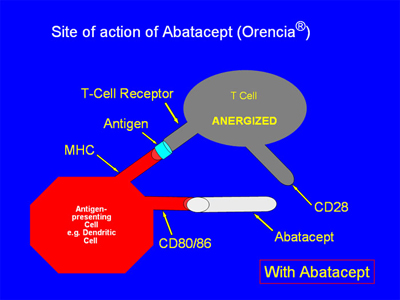

When abatacept is present, as in the illustration below, the CD 80/86 receptor on the APC binds with the abatacept, which acts as a “decoy” receptor. Thus, the CD80/86 receptor cannot bind to the CD28 receptor on the T-cell. There is thus only a “single signal”, and the T-cell is not activated:

Tocilizumab works by working as a blocker of the receptor of IL6, circled below:

Biologic Agents – Side Effects

A variety of infections have been described associated with the use of anti-TNF agents. Most common has been tuberculosis. For this reason, before any anti-TNF agent is used, the patient should have a PPD skin test or Quantiferon Gold skin test. If positive, and if the patient is previously untreated, treatment of latent tuberculosis is begun before the patient is given an anti-TNF agent. Anakinra seems less likely to activate tuberculosis than the anti-TNF agents.

Due to described worsening of multiple sclerosis in patients treated with biologic agents, and rare cases of new multiple sclerosis-like lesions developing in patients not symptomatic prior to starting a biologic agent, it is advised to use great caution in using anti-TNF agents in patients with multiple sclerosis. Other side effects of biologic agents include:

- Opportunistic infections in addition to tuberculosis: e.g., atypical mycobacteria, pneumocystis infection, histoplasmosis...

- Rare reports: pancytopenia and aplastic anemia

- Rare elevations liver function tests

- Lymphoma – so far increased risk not shown – data to date suggests that the rheumatoid arthritis disease severity is associated with risk of lymphoma and that adding TNF blockade does not increase lymphoma risk in adults

- Skin cancers (not melanoma): it appears that TNF blockers increase the risk of squamous cell and basal cell carcinomas of the skin. Patients on TNF blockers should get yearly total body skin checks.

JAK inhibitors for Rheumatoid Arthritis

JAK inhibitors block signaling pathways within the cell, and this blockade decreases the production of multiple inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6. The JAK inhibitor presently approved for rheumatoid arthritis is tofacitinib (Xeljanz®).

This is an oral medication taken at 5mg twice a day or 11mg once a day. It can be taken with or without methotrexate. As with the biologic agents, infection is the main concern from a toxicity point of view. Increased cases of shingles were seen in patients treated with tofacitinib, for example, so getting the shingles vaccine prior to starting tofacitinib therapy is important. Other JAK inhibitors are being studied at present.

Follow-Up of RA Treatment

It is important that long-term RA therapy be closely monitored. Some guidelines for follow-up of commonly used agents and monitoring for their adverse effects are as follows:

- Methotrexate: CBC + liver function tests + creatinine every 5 weeks, spaced out to every 3 months after long-term use

- Plaquenil: CBC + chemistry every 4 months, yearly ophthalmologist check (risk highest after 5 years of use)

- Azulfidine: CBC every 2 weeks and chemistry every month for 1st 3 months, then CBC + chemistry every 3 to 4 months

- TNF blocking agents: CBC + chemistry every 3 months

References on Rheumatoid Arthritis Management

The American College of Rheumatology provides management guidelines for managing inflammatory arthritis and for monitoring its therapy.

Updated: 2/1/2018

Authors

Attending Physician, Hospital for Special Surgery

Professor of Clinical Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College