Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is an uncommon but not exceptionally rare condition. It is often called “the great mimicker” because, as a systemic illness that can potentially affect any part of the body, it can look very different from patient to patient and resemble many other medical conditions.

What is sarcoidosis?

Sarcoidosis is a condition characterized by clusters of immune cells called granulomas, which can infiltrate different tissues anywhere in the body. It commonly affects the lungs and lymph nodes, but it can also form in the eyes, muscles, skin, heart, bones, or other organs. Sarcoidosis is not an infection, nor is it a cancer. Rather, it is a disease of dysregulated immunity, which means the body is not appropriately controlling its immune responses.

Sarcoidosis New York Community Group

Join the New York community group at the Foundation for Sarcoidosis Research and get updated information for associated events with HSS and more.

Next event: Osteoporosis and Sarcoidosis: A Delicate Balance to Maintain Bone Health Weds, Jan 15 at 6:30pm. Arthur Yee, MD, PhD, Director of the Sarcoidosis Collaborative will present on treatment and management of symptoms.

New participants sign up here

What causes sarcoidosis?

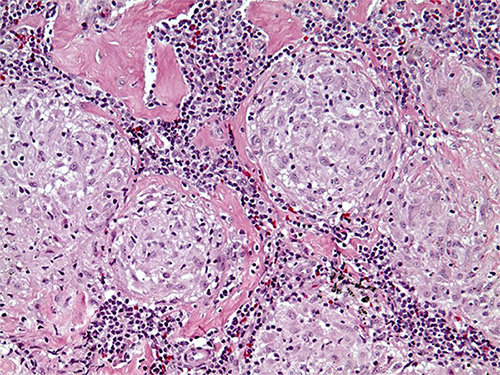

The ultimate causes of sarcoidosis are not known, but integral to its development are changes in the immune system that lead to a characteristic form of inflammation called noncaseating granulomas. These granulomas are clusters of white blood cells that your body has created to protect itself against something it perceives as harmful. In a person with sarcoidosis, however, these clusters form even when no such harmful substance is present. Although researchers have speculated on many potential triggers, no single causative agent has been identified.

Specimen from a patient with sarcoidosis demonstrating noncaseating granulomas.

What are the symptoms of sarcoidosis?

The symptoms of sarcoidosis will vary greatly from case to case and depend on which organs are affected. In fact, no list of potential symptoms can be completely exhaustive. Some patients may not have any symptoms at all, while others can have non-specific complaints like fever, fatigue, and weight loss, not unlike those commonly seen in other systemic inflammatory illnesses. Often, a diagnosis for sarcoidosis is made incidentally.

Sarcoidosis symptoms by organ

- The lungs are among the more commonly involved organs. Patients with lung involvement, or pulmonary sarcoidosis, may be asymptomatic, or they may have shortness of breath, coughing, wheezing, or other respiratory complaints.

- Numerous types of skin rashes, sometimes painful or disfiguring, can occur. Some more characteristic findings include small lumps at scars or tattoos, tender reddish bumps under the skin often around the shins and ankles (erythema nodosum), or raised red-purplish bumps on the face (lupus pernio).

- Eye inflammation (uveitis) can lead to discomfort, blurred vision, red and swollen eyes, light sensitivity, and even blindness if left unrecognized and unattended.

- The heart and nervous systems are particularly challenging areas. Patients with cardiac involvement may have no symptoms, or they may have palpitations, fainting spells, poor exercise tolerance, or shortness of breath. Neurologic disease can affect the central nervous system, peripheral nervous system, or autonomic nervous system, each of which can lead to a different neurologic complaint.

- Bone involvement in sarcoidosis is known as osseous sarcoid which can present with pain or swelling of the affected bone.

Some manifestations of sarcoidosis may be indirectly related to the inflammatory process. For example, vitamin D metabolism may become altered, which can cause high blood calcium levels and kidney problems.

X-ray image demonstrating osseous sarcoid in finger bones.

How is sarcoidosis diagnosed?

An experienced and knowledgeable team of physicians who know what is likely and unlikely to be sarcoidosis is essential to make the diagnosis. There is no one perfect diagnostic test. Sarcoidosis is diagnosed through the careful integration of a patient's symptoms and medical history, laboratory testing, pathologic findings, and radiologic (imaging) studies. Furthermore, other diseases such as infections, malignancies and systemic rheumatic diseases such as lupus need to be considered and excluded before a diagnosis is made.

Lung involvement is common in sarcoidosis, and so even in the absence of respiratory symptoms, appropriate diagnostic tests often include a chest X-ray and chest CT scanning, which can assess the lungs and lymph nodes. If indicated by these radiologic findings, a pulmonary specialist can also perform a bronchoscopy (examination of the airways using a special type of endoscope) to evaluate the bronchi and take a tissue sample or biopsy of the lung, aiding in both confirming the diagnosis and excluding other possibilities. Frequently, less invasive biopsies of lymph nodes, skin, or other more accessible tissues of suspected involvement can be performed to make the diagnosis.

While there is no single laboratory diagnostic blood test for sarcoidosis, the aggregate information gathered from many sources can be useful in bolstering the diagnosis. In addition to routine tests such as the complete blood count and the complete metabolic panel, other tests regularly ordered include angiotensin converting enzyme, vitamin D metabolites, and lysozyme.

Once the diagnosis of sarcoidosis is deemed likely, routine ophthalmologic examination and electrocardiography (EKG) are recommended, even when there are no eye or cardiac complaints, in order to identify subclinical disease.

It should be highlighted that equally important in the diagnostic process is to not fall into the frequent trap of attributing any or every symptom or finding to sarcoidosis.

Who typically gets sarcoidosis?

In the United States, sarcoidosis occurs in around 60 out of 100,000 people, making it roughly as common as lupus, and like lupus, it is more prevalent in the Black community. The disease is slightly more common in women. Most people are diagnosed between the ages of 25 to 40, but sarcoidosis can occur at any age. There are rare family clusters, but there is no one single gene associated with sarcoidosis.

Does sarcoidosis last a lifetime?

Most people with sarcoidosis live normal, healthy, and active lives. Once diagnosed, however, sarcoidosis should always be considered in the medical history, even when not symptomatic. It is not rare for patients to be asymptomatic for years or decades before developing their first manifestations that require intervention. Lofgren’s syndrome which is characterized by erythema nodosum (see above), ankle swelling and discomfort, and enlarged chest lymph nodes is one specific milder variant of sarcoidosis and often resolves within several months without recurrence and without long-term consequence.

How do you treat sarcoidosis?

There is no specific cure for sarcoidosis. Often, no pharmacologic intervention is necessary, but in all cases, vigilant monitoring is essential. This involves not only observant physicians, but just as importantly an informed patient.

When medicines are necessary, they should be targeted to the specific issues in each individual person, with the appropriate degree of aggressiveness. Arthritis can be treated with simple nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Skin problems can be treated with topical agents. When prompt or systemic treatment is necessary, corticosteroids such as prednisone are usually first-line choices to quickly quell inflammation. However, because of concerns over the side effects of corticosteroids with prolonged use, transitioning over to other immune-system-directed medications to attain long-term control over the disease is increasingly done. These other medicines, such as hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, and TNF inhibitors, are commonly used for other rheumatologic disorders and are thought to be safer over the long term but typically take longer to start working.

What type of doctor treats sarcoidosis?

Since sarcoidosis is a systemic condition with symptoms that vary greatly from patient to patient, management of this disease should, optimally, involve a team of clinicians from different specialties, each of whom have particular knowledge of the condition. Depending on the symptoms and how the disease manifests, the healthcare team will frequently include physicians from various disciplines, such as rheumatologists, pulmonologists, dermatologists, cardiologists, ophthalmologists, and neurologists.

Collaboration between physicians is essential to promote education, to engender research, and most importantly to improve patient care and treatment outcomes. The HSS Sarcoidosis Collaborative was designed to meet this need by providing patients with a coordinated program with integrated clinical support. (Find a doctor at HSS who treats sarcoidosis.)

Resources

- The Evolving Landscape of Sarcoidosis – video presentation by Arthur M. F. Yee, MD, PhD to the Chinese American Medical Society Journal Club, and co-hosted by HSS's LANtern® (Lupus Asian Network).

- Foundation for Sarcoidosis Research – the leading international organization dedicated to finding a cure for sarcoidosis and improving care for sarcoidosis patients through research, education, and support.

Differential diagnoses

Symptoms of sarcoidosis can resemble those of various rheumatic diseases, and so it is important to be assessed thoroughly by a team of appropriate clinical specialists. Learn more from the pages below.

Articles on related issues

These articles cover topics that may be of interest to people with sarcoidosis.

- What You Should Know About Taking DMARDs for Rheumatic Disease

- Steroid Side Effects: How to Reduce Drug Side Effects of Corticosteroids

- Guidelines to Help Reduce the Side Effects of NSAIDs (Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs)

- Synovectomy: Surgery for Inflammatory Arthritis

- Patient Guidelines to Help Reduce the Side Effects of Methotrexate

- Possible Environmental Triggers Associated With Autoimmune Diseases

- Doctor/Patient Communication

Sarcoidosis Patient Stories

Posted: 4/28/2023

Reviewed and edited by Arthur M. F. Yee, MD, PhD

References

(HSS Sarcoidosis Collaborative members are shown in boldface.)

- Loupasakis K, Berman J, Jaber N, Zeig-Owens R, Webber MP, Glaser MS, Moir W, Qayyum B, Weiden MD, Nolan A, Aldrich TK, Kelly KJ, Prezant DJ. Refractory sarcoid arthritis in World Trade Center-exposed New York City firefighters: a case series. J Clin Rheumatol. 2015 Jan;21(1):19-23. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000185. PMID: 25539429; PMCID: PMC4714559.

- Yee AMF. Sarcoidosis: Rheumatology perspective. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2016;30(2):334-356. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2016.07.001.

- Yee AMF. Treatment of sarcoidosis in US rheumatology practices: data from the American College of Rheumatology’s Rheumatology Informatics System for Effectiveness (RISE) Registry: comment on article by Hamman et al. Arthritis Care Res 74:2119-2120, 2022.