ACL Surgery

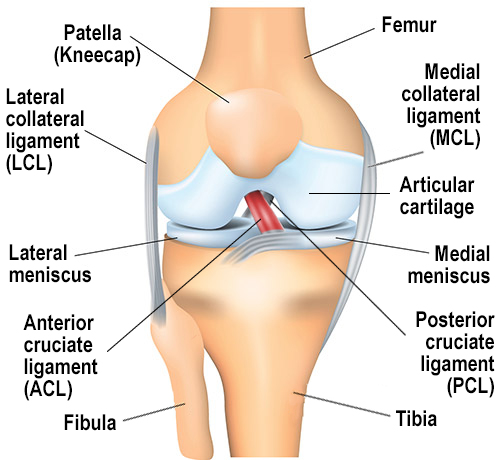

A partial or complete tear of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) in the knee is a common injury among athletes. The discussion below provides an overview of ACL surgical reconstruction and repair.

To learn more about the symptoms and diagnosis of a torn ACL, visit our ACL Tear page.

Complete ACL tears are usually treated by sports medicine physicians and orthopedic surgeons with an ACL reconstruction surgery, in which the torn ligament is replaced with a tissue graft to mimic the natural ACL. However, HSS takes an interdisciplinary approach to treating ACL injuries: Physiatrists, sports medicine physicians and orthopedic surgeons – along with radiology and rehabilitation professionals – collaborate to determine the best treatment option for each patient. In young patients who are still growing, care must be taken to protect during treatment. In these cases, it is best to consult a pediatric orthopedic specialist.

Because people who have had an ACL injury are more likely to develop osteoarthritis in the knee earlier in life than those who do not, HSS physicians and scientists also continually investigate ACL surgery techniques to improve the short-term and long-term outcomes for patients.

How do you know if you need ACL surgery?

The need for surgery depends on the severity of the ACL tear and the lifestyle of the patient. A completely torn ACL cannot heal on its own. Studies have shown, however, that in some young patients who experience a partial tear of the ACL, the ligament may heal without the need for surgery. In patients who have only a partial tear, nonsurgical treatment may be an option.

Patient lifestyle

People who have completely torn their ACL and who maintain an active lifestyle – especially competitive athletes – will be recommended for surgery to allow them to return to their prior level of activity and avoid future injury. Young patients who participate in cutting and pivoting sports (soccer, basketball, lacrosse, football) are at increased risk of meniscus injury if an ACL tear is left untreated. In some older patients or others whose lifestyles do not include rigorous exercise with side-to-side movements, nonsurgical treatments may allow them to return to normal routines without an intact ACL. Patients who participate in running, cycling, weightlifting, or exercise classes are able to return to these activities with a low risk of new injury.

HSS research enhances surgical outcome predictions

In a two-year patient study, HSS physician researchers tested the ability of machine learning algorithms to help predict which patients might experience significant improvement in their knee function after ACL reconstruction. Several of these, and especially elastic-net penalized logistic regression (ENPLR) algorithm proved useful and are now employed in the surgical decision-making process.

In the study, they found that the most common factors that may predict a patient’s improvement after surgery (“minimal clinically important difference” or MCID) are semi-modifiable and can assist with preoperative shared decision making between the surgeon and patient to better prepare the knee before surgery. In addition, the ENPLR algorithm was able to use data gathered from the patient before surgery and the postsurgical outcome scores reported by prior patients to predict the benefit of surgery, including return-to-play timing and other outcomes.

How soon should you get ACL surgery?

For a complete tear of the ACL, reconstruction surgery is generally scheduled between 3 to 6 weeks after the injury occurs. This allows inflammation in the area to subside and allows time for physical therapy sessions to focus on restoring normal knee flexion and extension. If surgery is performed too early and in patients with limited knee range of motion, patients may develop a profound scarring response called arthrofibrosis, which leads to stiffness of the knee joint. Delaying surgery beyond three months increases the risk of developing irreparable cartilage damage or meniscus injuries because of continual instability in the knee.

Orthopedic surgeons gauge the appropriate timing of reconstruction surgery based on:

- whether there are other injuries present that need to be treated first

- the physical appearance of the knee (how much swelling is present)

- the patient’s level of knee pain

- the patient's range of motion and quality of muscle control when flexing (bending) or extending (straightening) the leg

Some evidence suggests that delaying ACL reconstruction surgery for six months or longer after injury can not only increase the risk of sustaining a meniscus tear or cartilage injury, but also lead to increased risk of the need for a future ACL revision surgery.

How does ACL reconstruction surgery work?

In ACL reconstruction surgery, a new ACL is made from a graft of replacement tissue from one of two sources:

- a portion of the patient's own iliotibial band, hamstring, quadriceps or patellar tendon

- an allograft (tissue from a human organ donor)

The type of graft used for each patient is determined on a case-by-case basis, however allograft tissue is not advised for young patients due to the significantly higher risk of reinjury and graft failure.

ACL reconstruction surgery is performed using minimally invasive arthroscopic techniques, in which a combination of fiber optics, small incisions and small instruments are used. A somewhat larger incision is needed, however, to obtain the tissue graft. ACL reconstruction is an outpatient (ambulatory) procedure, in which patients can go home on the same day as their surgery.

Animation video: Torn ACL reconstruction surgery

View this animation for a more detailed description of a minimally invasive ACL reconstruction.

What is the recovery time for ACL surgery?

It usually takes 9 to 12 months for a patient to return to participating in sports after an ACL reconstruction, depending on the level of competition, the type of activity, and progress made with physical therapy.

Patients are able to walk with crutches and a leg brace on the day of surgery. The patient enters a rehabilitation program 2 to 3 days after surgery to restore strength, stability and range of motion to the knee. The rehabilitation process is composed of a progression of exercises:

- Quadriceps muscle strengthening and knee range-of-motion exercises are started early in the recovery period.

- Running exercises begin at about 3 to 5 months.

- Pivoting exercises are started at around 5 to 8 months.

- Return to playing competitive sports can depend largely on the sport. For example, participants in track and crew may be able to start at three months. But for cutting and pivoting sports like soccer or football, it is more like nine months until return to practice and 12 months to return to competition.

The degree of pain associated with ACL recovery varies by patient and is addressed successfully with medication. Recovery time also varies from patient to patient. The determination of when a patient has fully recovered is based on the restoration of muscle strength, range of motion and proprioception of the knee joint. Your surgeon may recommend completion of a return-to-sport test, which includes strength and agility measurements, at several intervals during your recovery to accurately gauge your progress with physical therapy and readiness to return to your desired sport.

It is critical that the patient have a rehabilitation period that is carefully supervised by an appropriate physical therapist, as well as to have follow-up appointments with the surgeon.

Learn more by reading ACL Surgery Recovery: Everything You Need to Know.

MRI showing a completely torn anterior cruciate ligament.

MRI showing a reconstructed anterior cruciate ligament.

Types of ACL surgery

ACL surgery usually involves a complete rebuilding of the ligament, as repair of the ligament is not usually possible. This procedure, called ACL reconstruction, is the current standard of care for surgically treating a torn ACL. Choosing the right surgical option for an ACL tear from the start can have lifelong implications, and it is critical to get ACL surgery right the first time.

ACL reconstruction versus ACL repair

ACL reconstruction is the current standard-of-care surgical treatment for ACL tears. This procedure typically uses a graft, or a piece of tissue, that is placed in the knee to replace the torn ACL in a minimally invasive surgery that uses small incisions. Most ACL surgeries performed at HSS are ACL reconstructions. Imaging studies have demonstrated that ACL reconstruction can help protect patients from developing osteoarthritis of the knee.

ACL repair is an older technique that involved sewing the torn ACL tissue back together with sutures, rather than rebuilding it with a graft. Today, ACL repair has been modernized, and some surgeons feel that modern ACL repair techniques may be performed safely and may lead to a quicker recovery than ACL reconstruction. However, the data on outcomes is limited, and failure rates for ACL repair appear to be between 5 and 10 times higher than those for ACL reconstruction in people of all ages. This results in graft failure rates as high as 50% in adolescent patients.

The bridge-enhanced ACL repair (BEAR) procedure is another type of ACL repair procedure that uses a bovine-derived tissue to augment an ACL repair. This procedure has promising outcomes, but many studies are currently ongoing to evaluate how patients perform with this procedure. It is not advised to use this procedure for patients under 22 years of ae due to high risk of failure.

When ACL surgery fails, surgeons must do a revision surgery (a second operation) to reconstruct the torn ACL graft. If a repaired ACL fails, it can only be revised with an ACL reconstruction. Having to redo any kind of ACL surgery results in higher rates of failure, lower rates of successful return to sports activity, and increased risk of developing osteoarthritis in the knee. It is important for patients of all ages to have a successful surgery the first time, but it is particularly important for young athletes. For them, a failed surgery can be devastating: In the short term, it can mean that they lose years away from their chosen sport. In the longer term, it can lead to chronic pain and loss of knee function.

ACL reconstruction surgery steps

Reconstruction of the ACL follows a number of basic steps, although they may vary slightly from case to case:

- The orthopedic surgeon makes small incisions around the knee joint, creating portals of entry for the arthroscope camera and surgical instruments.

- The arthroscope is inserted into the knee and delivers saline solution to expand the space around the joint. This makes room for surgical tools, including the arthroscopic camera, which sends video to a monitor so that the surgeon can see inside the knee joint.

- The surgeon then evaluates structures that surround the torn ACL, including the left and right meniscus and the articular cartilage. If either of these soft tissues have any lesions, the surgeon repairs them.

- Next the graft will be harvested (unless a donor allograft is used). A section of tendon from another part of the patient's body is cut to create a graft. Graft can be used from the patient’s iliotibial band, hamstring tendons, or kneecap tendons (quadriceps or patellar tendons).

- Over time, the graft will grow into the bone.

What kind of anesthesia is used for ACL surgery?

At HSS, most patients who undergo ACL reconstruction are given an epidural nerve block during their surgery, rather than being placed fully unconscious under general anesthesia. This epidural is the same type of regional anesthesia many women receive during childbirth. Patients also receive a localized nerve block around the knee that lasts between 18 to 24 hours after surgery. Previous studies have found that the nerve block used at HSS (the adductor canal block) is safe and does not affect muscle strength or recovery after surgery.

Can a teenager have ACL surgery?

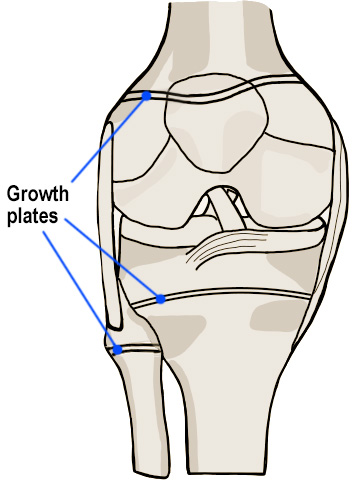

Children and younger teenagers who are still growing cannot have the same type of ACL surgery as an adult or older adolescents, but recent surgical innovations have made it possible for youth athletes to have ACL reconstruction surgery.

The standard method of ACL reconstruction can be performed successfully on older teenagers who are done growing. But performing ACL reconstruction on a growing child is unique, because the typical method used for adults can cause damage to open growth plates, which can lead to uneven limb lengths or angular deformities. Therefore, it used to be that surgeons postponed ACL surgery until children stopped growing, or used surgical techniques that were not anatomically accurate.

But innovations in surgical techniques now provide a variety of options for treating an ACL tear in younger children and adolescents. One option is called the All-Inside, All-Epiphyseal Reconstruction (AE-ACLR). The technique is similar to adult ACL surgery but uses new technology and intraoperative X-rays to place the new ACL graft anatomically in the knee, without the graft crossing the adjacent growth plates. It is performed arthroscopically and results in a near anatomic ACL reconstruction with a very high rate of return to play. This can be welcome news to child athletes who, without surgery, would simply have to stop playing sports until they had finished growing.

Surgeons can also perform ACL reconstruction using a patient’s own iliotibial band (ITB) tissue without drilling any holes or tunnels around the growth plates. This is performed arthroscopically and has demonstrated in several studies to have a low graft failure (re-tear) rate and high rate of return to normal sports activities. Because no tunnels or holes are drilled around the growth plates, it is safe to use in growing children of any age.

Pediatric patients should follow similar rehabilitation protocols as adult patients to ensure appropriate progress after surgery. Additionally, pediatric patients should undergo a formal return to sport test prior to returning to activities, to ensure that the patient has regained strength and agility to safely return to sports.

Articles related to ACL surgery

Read more about ACL injuries and ACL surgery, including ways to avoid tearing your ACL. Here, you can also learn about related knee conditions.

- Can You Have Surgery With a Cold?

- ACL Surgery Recovery: Everything You Need to Know

- Revision ACL Reconstruction

- ACL Tear and MCL Tear: Key Differences and Treatment Options for Individual and Combined Injuries

- Knee Arthroscopy for ACL Reconstruction, Meniscal Repair, and Other Knee Problems

- ACL Injury Prevention Tips and Exercises

- Meniscus Surgery: Meniscectomy, Transplant, and Repair

- Will I Feel Pain After Surgery?

- How Isometric Exercise Can Improve Your Mobility

ACL Surgery Success Stories

Updated: 7/18/2024

Reviewed and updated by Shevaun Mackie Doyle, MD; Peter D. Fabricant, MD, MPH; Stephen Fealy, MD;

Daniel W. Green, MD, MS, FAAP, FACS Michelle E. Kew, MD; Madeline Kratz, PA-C, MMSc.

References

- Forsythe B, Lu Y, Agarwalla A, Ezuma CO, Patel BH, Nwachukwu BU, Beletsky A, Chahla J, Kym CR, Yanke AB, Cole BJ, Bush-Joseph CA, Bach BR, Verma NN. Delaying ACL reconstruction beyond 6 months from injury impacts likelihood for clinically significant outcome improvement. Knee. 2021 Oct 30;33:290-297. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2021.10.010. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34739960. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34739960/

- Gagliardi AG, Carry PM, Parikh HB, Traver JL, Howell DR, Albright JC. ACL Repair With Suture Ligament Augmentation Is Associated With a High Failure Rate Among Adolescent Patients. Am J Sports Med. 2019 Mar;47(3):560-566. doi: 10.1177/0363546518825255. Epub 2019 Feb 7. PMID: 30730755. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30730755/

- Hughes JD, Lawton CD, Nawabi DH, Pearle AD, Musahl V. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Repair: The Current Status. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020 Nov 4;102(21):1900-1915. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.20.00509. PMID: 32932291. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32932291/

- James EW, Dawkins BJ, Schachne JM, Ganley TJ, Kocher MS; PLUTO Study Group; Anderson CN, Busch MT, Chambers HG, Christino MA, Cordasco FA, Edmonds EW, Green DW, Heyworth BE, Lawrence JTR, Micheli LJ, Milewski MD, Matava MJ, Nepple JJ, Parikh SN, Pennock AT, Perkins CA, Saluan PM, Shea KG, Wall EJ, Willimon SC, Fabricant PD. Early Operative Versus Delayed Operative Versus Nonoperative Treatment of Pediatric and Adolescent Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2021 Dec;49(14):4008-4017. doi: 10.1177/0363546521990817. Epub 2021 Mar 15. PMID: 33720764. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33720764/

- Kew ME, Bodkin S, Diduch DR, Brockmeier SF, Lesevic M, Hart JM, Werner BC. Reinjury Rates in Adolescent Patients 2 Years Following ACL Reconstruction. J Pediatr Orthop. 2022 Feb 1;42(2):90-95. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000002031. PMID: 34857725. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34857725/

- Kew ME, Bodkin SG, Diduch DR, Smith MK, Wiggins A, Brockmeier SF, Werner BC, Gwathmey FW, Miller MD, Hart JM. The Influence of Perioperative Nerve Block on Strength and Functional Return to Sports After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2020 Jun;48(7):1689-1695. doi: 10.1177/0363546520914615. Epub 2020 Apr 28. PMID: 32343596. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32343596/

- Kocher MS, Heyworth BE, Fabricant PD, Tepolt FA, Micheli LJ. Outcomes of Physeal-Sparing ACL Reconstruction with Iliotibial Band Autograft in Skeletally Immature Prepubescent Children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018 Jul 5;100(13):1087-1094. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.17.01327. PMID: 29975275. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29975275/

- Kunze KN, Pareek A, Nwachukwu BU, Ranawat AS, Pearle AD, Kelly BT, Allen AA, Williams RJ 3rd. Clinical Results of Primary Repair Versus Reconstruction of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Contemporary Trials. Orthop J Sports Med. 2024 Jun 11;12(6):23259671241253591. doi: 10.1177/23259671241253591. PMID: 38867918; PMCID: PMC11168252. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38867918/

- Kunze KN, Polce EM, Ranawat AS, Randsborg PH, Williams RJ 3rd, Allen AA, Nwachukwu BU; HSS ACL Registry Group; Pearle A, Stein BS, Dines D, Kelly A, Kelly B, Rose H, Maynard M, Strickland SM, Coleman S, Hannafin J, MacGillivray J, Marx R, Warren R, Rodeo SA, Fealy S, O'Brien S, Wickiewicz T, Dines JS, Cordasco FA, Altcheck D. Application of Machine Learning Algorithms to Predict Clinically Meaningful Improvement After Arthroscopic Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Orthop J Sports Med. 2021 Oct 14;9(10):23259671211046575. doi: 10.1177/23259671211046575. PMID: 34671691; PMCID: PMC8521431. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34671691/

- Murray MM, Kalish LA, Fleming BC; BEAR Trial Team; Flutie B, Freiberger C, Henderson RN, Perrone GS, Thurber LG, Proffen BL, Ecklund K, Kramer DE, Yen YM, Micheli LJ. Bridge-Enhanced Anterior Cruciate Ligament Repair: Two-Year Results of a First-in-Human Study. Orthop J Sports Med. 2019 Mar 22;7(3):2325967118824356. doi: 10.1177/2325967118824356. PMID: 30923725; PMCID: PMC6431773. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30923725/

- Nwachukwu BU, Patel BH, Lu Y, Allen AA, Williams RJ 3rd. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Repair Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review of Recent Literature. Arthroscopy. 2019 Jul;35(7):2233-2247. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2019.04.005. PMID: 31272646. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31272646/

- Potter HG, Jain SK, Ma Y, Black BR, Fung S, Lyman S. Cartilage injury after acute, isolated anterior cruciate ligament tear: immediate and longitudinal effect with clinical/MRI follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2012 Feb;40(2):276-85. doi: 10.1177/0363546511423380. Epub 2011 Sep 27. PubMed PMID: 21952715. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21952715/