Patellofemoral Arthritis of the Knee: Diagnosis and Treatment

Knee arthritis affects more than four million Americans annually. It occurs when degenerative changes develop in the cartilage that lines the knee joint. In most cases, it affects one or both sides of the joint between the tibia (shin bone) and the femur (thighbone). But patellofemoral arthritis, sometimes called kneecap arthritis, is different.

What is patellofemoral arthritis?

Patellofemoral arthritis is a rarer form of knee arthritis in which the arthritic degeneration affects only the patellofemoral compartment of the knee joint. As with other patellofemoral joint disorders, it is more frequently seen in women than in men.

Knee joint anatomy

The knee is a complex joint formed where four bones meet. These are:

- the femur (thighbone)

- the patella (kneecap)

- the tibia (shinbone) – the larger long bone of the lower leg

- the fibula – the smaller long bone of the lower leg

The joint has three main compartments, which each have individual functions and structures:

- The inner (medial) compartment and the outer (lateral) compartments are formed by the articulation (or joining) of the lowest part of the thighbone (femur) and the highest part of the shinbone (tibia).

- The third compartment of the knee is formed by the kneecap (patella) and the front part of the femur and is called the patellofemoral joint.

The first two compartments are the most important for walking or running on flat terrain. The third compartment (patellofemoral joint) is engaged during activity like walking on inclined terrain or on stairs, climbing, kneeling, squatting.

What are the symptoms of patellofemoral arthritis?

Symptoms include pain in the front the knee, just behind the patella (kneecap), along with stiffness and, often, swelling. These typically get worse while walking up or downhill, climbing or descending stairs, squatting, kneeling or rising from a seated position. It is common to experience no symptoms while walking on level ground.

How is patellofemoral arthritis diagnosed?

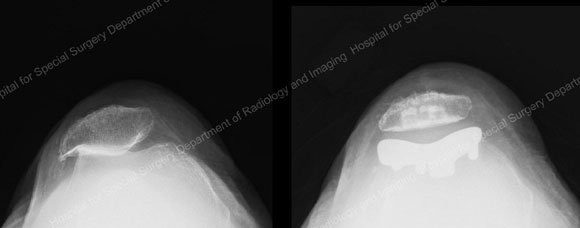

Patellofemoral arthritis is diagnosed when there is significant loss of cartilage from the joint surface of the patella and the trochlea (the groove in the femur where the kneecap rests). The diagnosis is restricted to arthritis seen only in this compartment of the knee. (If degenerative changes are also present in the lateral, medial and patellofemoral compartment, this instead indicates tricompartmental osteoarthritis of the knee.)

People who develop patellofemoral arthritis generally receive one of three diagnoses:

- Post-instability arthritis: the result of cartilage damage that occurs with multiple dislocations or subluxations in the joint

- Post-traumatic arthritis: cartilage damage that results from a fall or other traumatic injury to the knee that then progresses over time to arthritis, or

- Overload osteoarthritis: a condition that resembles osteoarthritis in any other joint, i.e., a gradually progressive thinning of the cartilage related to “normal wear and tear” that in this case is restricted to, or starts in, the patellofemoral compartment of the knee.

What causes patellofemoral arthritis?

The biomechanics of women (wider hips an often increased angle of the thighbone as compared to men) make them more susceptible to forces that cause this condition. Other anatomical alignment issues may further predispose a person to the condition. These may be determined with radiographs (X-rays) or MRI imaging. For example, one radiographic parameter frequently found to be abnormal in patients with patellofemoral arthritis is called a “Q angle.”

Named after the quadriceps muscle, the Q angle is the angle formed between the quadriceps muscle that runs down the front of the thigh and its attachment through the patellar tendon below the knee joint. The patella is embedded in this “musculotendinous complex” that allows the patient to straighten the knee. It tracks on a perfectly matched “rail” provided by the trochlea of the femur, much like a train on a track. A Q angle exceeding normal range indicates that the patella is being pulled laterally (to the side), and the joint is no longer congruent. This places abnormal stress on the patellofemoral joint, leading to progressive wear and tear of the soft cushion of the joint (cartilage). “Women tend to have higher Q angles than men, predisposing them to this condition that typically manifests during the third and fourth decades of life.”

Another factor predisposing patients to patellofemoral arthritis is excessive hip anteversion (also known as femoral anteversion), a condition in which the neck of the femur rotates too far forward in the hip socket, resulting in additional lateral (sideways) pull on the patella. In addition, patellofemoral arthritis is more common in patients with patellofemoral dysplasia. In these patients the trochlea groove (femoral side) is misshapen and no longer matches the patella surface, increasing contact stresses and therefore resulting in early cartilage deterioration.

Some patients with loose patellar ligaments and the previously mentioned anatomical abnormalities resulting in severe “maltracking” of the patella can suffer episodes of complete “derailment” (dislocation) of the patella. “This condition – known as patellar instability – also predisposes patients to early patellofemoral arthritis, as each dislocation episode further damages the cartilage coating on the patella and/or trochlea.

The anatomical phenomena that lead to patellofemoral arthritis usually affect both legs. Therefore, patients may develop a similar problem in both knees. Even if you are experiencing pain in only one knee, it is often wise to have imaging studies on both knees.

What are nonsurgical treatment options for patellofemoral arthritis?

Treatment for patellofemoral arthritis usually begins with non-operative measures. These include activity modification, physical therapy, over-the-counter pain medications or, in some cases, one or more type of injection therapy.

Patients can adapt their activity to avoid stairs, limit squats and lunges, and decrease their participation in impact sports. Physical therapy will help stretch and strengthen surrounding muscles, while the se of medication such as acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen can relieve pain and inflammation.

For patients with mild to moderate arthritis who are experiencing an acute flare of their condition with swelling, corticosteroid injections, which reduce inflammation, can be effective. Good results are also being seen with viscosupplementation, in which a substance that mimics naturally occurring synovial fluid is injected into the joint to help lubricate it and minimize friction. In patients who are overweight, weight loss can help reduce the amount of stress applied to the knee. Bracing the knee is generally not helpful in people with patellofemoral arthritis.

What is the surgery for patellofemoral arthritis?

Surgical options range from to procedures to correct knee alignment problems (which may include ligament releases and/or an osteotomy or tibial tubercle transfer surgery) to type of partial knee replacement called patellofemoral joint replacement or, in some cases total knee replacement. Numerous factors determine which treatment is appropriate for each patient.

Dr. Shubin Stein points out that “the age of the patient and the amount of cartilage damage often dictates the surgical treatment options.” For example, in younger patients with mild cartilage changes, the orthopedist may suggest a lateral release, a procedure in which the tight ligaments on the outer side of the kneecap are cut to achieve better alignment and tracking of the kneecap and allow a smoother, less painful motion in the joint. Most surgeons agree that a lateral release is rarely indicated in isolation and should not be performed if more advanced cartilage damage is encountered.

“Determining whether the arthritis is the result of an alignment issue, or whether it is the beginning of an ongoing process that will eventually affect the entire knee is extremely important,” Dr. Sabrina Strickland notes. People who do not respond to nonsurgical treatment may be candidates for a patellofemoral joint replacement. Patients who do best with patellofemoral joint replacement are those in whom the arthritis is not expected to progress: those with post-instability arthritis and those with post-traumatic arthritis, “These are patients who are unlikely to ever need a total knee replacement."

Patellofemoral joint replacement allows the orthopedic surgeon to replace only the affected area of the knee, the patellofemoral joint, and to leave the healthy medial and lateral compartments intact. (Unicompartmental surgeries to address arthritis in each of those compartments are also an option for patients with arthritis in those portions of the knee.)

During this procedure the orthopedic surgeon removes the damaged cartilage and a small amount of bone from the joint surface of the patella and replaces it with a cemented high-density plastic button or patella implant. Damaged cartilage and a small amount of bone are also removed from the joint surface of the trochlear groove, which is replaced with a very thin, metal laminate which is cemented in place. “The goal is to eliminate friction and restore a smoothly gliding motion in the joint,” Dr. Beth Shubin Stein explains.

In addition to partial knee replacement, patients with post-instability arthritis due to malalignment may also require soft-tissue procedures and/or osteotomy or tibial tubercle transfer surgery to realign the knee. This mitigates the possibility of subsequent dislocations. Patients who require more than one procedure may have them done either in stages or during a single operation.

Many of the patients Dr. Strickland sees, are patients without a history of instability or trauma. They have isolated patellofemoral arthritis where it is likely the first or early presentation of osteoarthritis which may progress at some point to involve the rest of the knee. These are typically women in their 50s or 60s who experience pain and stiffness during certain activities and transitioning from sitting to standing. The knee is not painful with all activities and they are able walk on level surfaces without discomfort. While the symptoms are restricted to the patellofemoral compartment at the time of diagnosis, some arthritic changes may be observable in images of the rest of the knee.

“When I discuss surgical options with these patients, I let them know that although a patellofemoral knee replacement will address their symptoms, we can’t know with absolute certainty whether they will eventually require a total knee replacement. However, there are numerous advantages to the partial knee replacement, including a much faster recovery, and the sensation that the knee still feels ‘normal’,” Dr. Strickland notes.

For many of these patients, the promise of a decrease in pain and an improvement in function for years to come is acceptable. If a total knee replacement becomes necessary, their partial knee replacement will not compromise the results of this subsequent surgery.

Patellofemoral joint replacement recovery

As compared to total knee replacement, partial knee replacement will speed the postoperative rehabilitation and offers the potential for excellent function. At Hospital for Special Surgery we have established a partial knee replacement rehabilitation pathway that will offer patients discharge from the hospital within 1 to 2 days compared to 3 to 4 days after total knee replacement surgery. The patient will require intensive physical therapy during a period that ranges from 6 to 12 weeks (three months) to achieve the best possible outcome.

Partial knee replacement has a low risk of perioperative complications. However, the procedure does have some of the same potential post-surgical complications as total knee replacement, including deep venous thrombosis (blood clot), delayed wound healing, and implant infection, as well as implant wear and loosening. Other complications are much less common than in total knee replacement, including nerve damage or the need for blood transfusions.

“While we today try to minimize the surgical trauma during total knee replacement with minimal invasive implantation techniques, partial knee replacements are truly minimally invasive since they spare large parts of the joint and do not alter the motion pattern (kinematic) by preserving the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments, which are usually removed during total knee replacement,” explains Dr. Shubin Stein.

Authors

Orthopedic Director, Women's Sports Medicine Center, Hospital for Special Surgery

Attending Orthopedic Surgeon, Hospital for Special Surgery

Attending Orthopedic Surgeon, Hospital for Special Surgery

Associate Professor of Orthopedic Surgery, Weill Cornell Medical College