Hip Arthritis

Hip arthritis is one of the most commonly treated conditions at HSS.

How does the hip joint work?

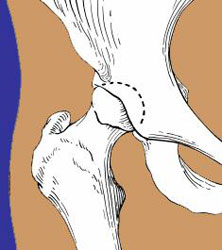

The hip is a ball-and-socket joint. The ball, at the top of the femur (thighbone) is called the femoral head. The socket, called the acetabulum, is a part of the pelvis. The ball moves in the socket, allowing the leg to rotate and move forward, backward and sideways.

In a healthy hip, the ball and socket are covered by a glistening layer called articular cartilage. This cartilage, which can be seen on an X-ray as the space in between the ball and the socket, is what allows the bones of the hip joint to glide together smoothly – with less resistance than ice sliding on ice. In addition, there is a special layer of exceptionally strong cartilage in the acetabulum called the labrum. The structure of the hip joint gives it a wide range of motion. It is a very stable joint because of the large area of between the femoral head and the labrum-lined acetabulum.

Illustration and X-ray image of a healthy hip joint.

What is hip arthritis?

Hip arthritis is where cartilage in the hip joint wears down or is damaged, leaving the bone surfaces of the joint to grind together and become rough. This causes pain and stiffness, making it difficult to move the leg.

There are different forms of hip arthritis, but all involve a loss of cartilage in the hip joint that eventually leads to bone rubbing on bone and destruction of the joint.

X-Ray of an arthritic hip

What causes hip arthritis?

Osteoarthritis is the most common type of arthritis to affect the hip. This is simply wear and tear of the joint over time, and it usually occurs in people aged 60 and older. Most people will experience some form of osteoarthritis as they age.

The joints that become affected, how badly, and at what age vary from person to person, depending upon other factors specific to each individual, such as:

- anatomic structure of the hip (the natural strength and/or angles of a person's bones)

- weight

- activity level

Other underlying conditions can cause of hip arthritis in younger patients. These include:

- autoimmune inflammatory diseases such as:

- infections

- traumatic hip injuries (such as a severe hip fracture)

- anatomic irregularities that place strain on the joint, leading to premature cartilage deterioration, such as:

The likelihood of getting hip arthritis increases with family history and advancing age. Patients who are overweight and those who have undergone trauma to the hip joint may also experience increased wearing out of cartilage.

Unfortunately, once the arthritic process begins, progression is almost always inevitable. The end result of all these processes is a loss of the cartilage of the hip joint, leading to bone-on-bone rubbing in the hip. However, the degree of pain and disability experienced by people with arthritis varies considerably.

What are the symptoms of hip arthritis?

For osteoarthritis of the hip, symptoms may include:

- aching pain in the groin area, outer thigh and buttocks

- joint stiffness

- reduced range of motion (for example, difficulty putting on shoes and socks)

In people who have hip osteoarthritis, walking and other motion that stresses the diseased hip cartilage usually increases pain symptoms and reduce a person's ability to be active levels. At the same time, reduced activity – not moving the body much – can weaken the muscles that control the hip joint, which may make it even more difficult to perform daily activities.

Because of the loss of the gliding surfaces of the bone, people with arthritis may feel as though their hip is stiff and their motion is limited. Sometimes people actually feel a sense of catching, snapping or clicking within the hip. The pain is usually felt in the groin, but also may be felt on the side of the hip, the buttock and occasionally down into the knee. Activities such as walking long distances, standing for long periods of time or climbing stairs puts stress on the hip that generally makes arthritis pain worse.

In people who have rheumatoid arthritis in the hip, pain is usually worst after periods of rest and inactivity, such as first thing after waking up in the morning. This is because the inactivity causes the joints to stiffen. Pain is often relieved after a period of walking or other activity as the joint becomes more flexible. Some rheumatoid arthritis patients may experience pain, swelling, redness and warmth, especially in the morning.

If I have arthritis in one hip, will I get it in the other?

People who have osteoarthritis in one hip will not necessarily get it in the opposite hip. In those who do develop this condition in both hips, one hip may reach the advanced stage before the other. People with rheumatoid arthritis are more likely to have symptoms in both hips.

How is hip arthritis treated?

Depending upon the severity of arthritis and the patient’s age, hip arthritis may be managed in a number of different ways. Treatment may consist of nonsurgical or surgical methods, or a combination of both.

Nonsurgical treatments for hip arthritis

Nonsurgical approaches that reduce pain and disability include:

- activity modification (reducing or stopping activities that cause pain)

- weight loss (to reduce strain on the joint)

- physical therapy

- NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication drugs) such as:

- ibuprofen (Advil)

- naproxen (Aleve)

- Cox-2 inhibitors such as celecoxib(Celebrex)

- injection therapies, such as corticosteroid, PRP, or hyularonic acid injections

The first line of treatment of hip arthritis includes activity modification, anti-inflammatory medication, hip injections and weight loss. Weight loss helps decrease the force that goes across the hip joint. Giving up activities that make the pain worse may make this condition bearable for some people. Anti-inflammatory medications such as ibuprofen, naproxen and the newer Cox-2 inhibitors help alleviate the inflammation that may be contributing to the pain. Furthermore, studies have shown that walking with a cane (in the hand on the opposite side of the hip that is in pain) significantly decreases the forces across the hip joint.

A combination of these non-operative measures may help ease the pain and disability caused by hip arthritis.

Surgical treatments for hip arthritis

If the non-operative methods have failed to make a person's condition bearable, surgery may be the best option to treat hip arthritis. The exact type of surgery depends upon a patient's age, anatomy, and underlying condition.

Surgical options for hip arthritis range from operations that preserve the hip joint to those that completely rebuild it. They include:

- Hip preservation surgeries: These are operations that prevent damaged cartilage from wearing down further. They include:

- Hip osteotomy: Cutting the femur or pelvic bone to realign its angle in the joint to prevent cartilage. An osteotomy may be appropriate if the patient is young and the arthritis is limited to a small area of the hip joint. It allows the surgeon to rotate the arthritic bone away from the hip joint, placing weightbearing on relatively uninvolved portions of the ball and socket. The advantage of this type of surgery is that the patient’s own hip joint is retained and could potentially provide many years of pain relief without the disadvantages of a prosthetic hip. The disadvantages include a longer course of rehabilitation and the possibility that arthritis could develop in the newly aligned hip.

- Hip arthrotomy: This is where the joint is opened up to clean out loose pieces of cartilage, remove bone spurs or tumors, or repair fractures.

- Hip arthroscopy: In this minimally invasive surgery, an arthroscope is used to clean out loose bodies in the joint or to remove bone spurs.

-

Joint fusion (arthrodesis): In this treatment, the pelvis and femur are surgically connected with pins or rods to immobilize the joint. This relieves pain but makes the hip permanently stiff, which makes it more difficult to walk.

- Total or partial joint replacement surgery

- Total hip replacement: Also known as total hip arthroplasty, this is the removal of the ball and socket of the hip, which are replaced with artificial implants.

- Partial hip replacement: Also called hemiarthroplasty, this involves replacing only one side of the hip joint – the femoral head – instead of both sides as in total hip replacement. This procedure is most commonly done in older patients who have had a hip fracture.

- Hip resurfacing: In this alternative to total hip replacement (appropriate for some patients), the arthritic cartilage and acetabulum (socket) are replaced, but the person's natural femoral head is preserved.

Further reading related to hip arthritis

Learn more from the articles and other content below, or select Treating Physicians to find the best arthritis doctor at HSS for your specific condition and insurance.

Articles related to diagnosing hip arthritis

Read about how X-rays and other imaging technologies are used to help physicians diagnose conditions that cause hip pain.

Articles on treatments for hip arthritis

Get a deeper dive on treatment methods related to hip arthritis.

Hip Arthritis Success Stories