MCL Tear / MCL Injury of the Knee

This page discusses injuries of the medial collateral ligament (MCL) in the knee. (For MCL injuries of the elbow, see UCL Injury.) Knee MCL injuries are common among players of contact sports with frequent pivoting, such as soccer, football, basketball, and hockey. They can also result from falls or poor landings during activities such as skiing, hiking, climbing or physical labor.

What and where is the MCL?

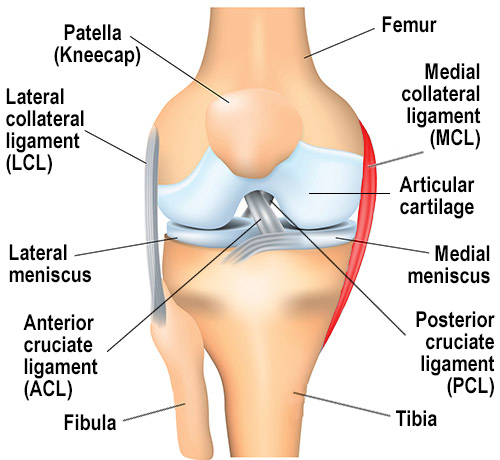

The medial collateral ligament, commonly referred to as the MCL, is a thick and strong ligament located along the inner side of the knee. The MCL stretches from the femur (thighbone) to the tibia (shinbone) and helps to stabilize the medial (inner) part of the knee.

While several other ligaments and tendons, such as the hamstring tendons, provide additional support, the MCL is the most important structure to prevent the knee from collapsing into a knock-kneed stance.

Anteroposterior (front-to-back) view of the right knee, with the MCL higlighted in red.

How does an MCL injury occur?

The MCL is often injured by forceful contact to the outside the knee while the foot is planted on the ground. This subjects the knee to a valgus force, in which the tibia (shinbone) bends inward relative to the femur (thighbone). Examples include when a football offensive lineman gets “rolled up” by another player from the side or when a soccer player forcefully strikes the inner side of the lower leg during a slide tackle. The MCL can be injured within the ligament itself or at its attachment site on the femur or the tibia.

Although the MCL may be torn in isolation, it is often injured in conjunction with the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and/or the medial meniscus, which is directly connected to the MCL.

What are the risk factors for an MCL injury?

Athletes who participate in competitive professional, club or school-affiliated sports activity are at greatest risk, particularly soccer, basketball, and football. Skiers are also at risk for MCL injuries due to the rotational forces exerted on the knee during a skiing accident.

What is an MCL sprain versus an MCL tear?

An MCL sprain is an excessive stretching or partial tear in the fibers of e the ligament. An MCL tear refers to a complete rupture of the ligament. A complete tear of the MCL can occur either where it attaches to the femur or to the tibia. MCL injuries are categorized into three grades, which are determined by symptoms and a doctor's findings during the physical exam:

- Grade I – stretching of the MCL

- Grade II – partial tear

- Grade II – complete tear

What are the symptoms of an MCL tear?

While symptoms of an MCL sprain include pain, tenderness and swelling of the medial (inner) side of the knee, they generally do not result in instability. Patients may feel pain or a sensation of instability with activities that stretch the inner side of the knee, such as getting out of a car or sleeping on the unaffected side. They may also notice difficulty walking due to knee swelling and pain to the inner side of the knee and may require crutches initially after an injury.

Unlike the ACL, the MCL is not located within the knee joint but on the inner side of it. For this reason, swelling within the knee joint itself suggests an associated injury to other structures of the knee, such as the meniscus, cartilage, or other ligaments, including the ACL.

How can I tell if I tore my MCL?

Some people describe feeling or hearing a “pop” at the moment of injury, with pain localized to the inner side of the knee. For the first few days after the injury, the inner part of the knee can be swollen and bruised or “black and blue” (ecchymotic), and it is often tender to the touch. If you think you may have a ligament injury, you should see a doctor as soon as possible.

What kind of doctor should I see if I think I tore my MCL?

If you suspect an MCL injury, it is important to be evaluated by a physiatrist, sports medicine physician or orthopedic surgeon so that the most appropriate treatment can be determined. (Find a doctor at HSS who can diagnose and treat an MCL injury.)

How is an MCL injury diagnosed?

A doctor can usually diagnose an MCL injury based solely on the patient’s history and physical examination, with specific physical exam maneuvers that test the stability of the MCL, for example, keeping the femur stable while pushing outwardly on the tibia to test the MCL’s stability. Therefore, an X-ray or MRI is not always necessary but are generally obtained when needed to evaluate for possible associated injuries to other ligaments, the meniscus, or knee cartilage.

However, X-rays of the knee should be considered in patients with an acute knee injury. In particular, children and teenagers suspected to have an MCL injury need radiographs to assess for associated fractures through the growth plate at end of the femur and/or tibia. An MRI of the knee can be obtained to characterize the location of the MCL injury, as this can inform treatment decisions, as well as to evaluate for other associated injuries to the knee.

Can you still walk with a torn MCL?

Yes, patients are able to walk with a torn MCL, but may require use of a brace and/or crutches due to pain or knee swelling, or if additional soft-tissue structures are injured alongside the MCL tear.

Can an MCL tear heal on its own?

Yes, the majority of MCL tears heal on their own. Partial MCL tears and stretch injuries heal on their own with non-surgical treatment methods. Complete MCL tears that have an injury to the femoral attachment can also heal on their own but will be carefully monitored by your doctor to make sure that the ligament stability is restored. Complete MCL injuries that have an injury to the tibial attachment are generally recommended for surgical treatment, as the MCL has poor healing capacity at this injury site.

How is an MCL injury treated?

The vast majority of MCL injuries can heal without surgery using conservative methods. The correct treatment will depend upon the severity of the injury, that is whether the ligament is just stretched, versus a partially or completely torn MCL. Rest and bracing are the common initial nonsurgical treatments, with physical therapy starting one to two weeks after injury to restore knee movement and strength while protecting the injured MCL. MCL surgery is reserved for cases where the medial collateral ligament fails to heal and restore stability to the inner knee even after a period of rest, or in cases where the ligament is completely torn from the tibial attachment.

Rest and bracing

In order to allow healing, the knee should be rested for several weeks. Frequent application of ice and a compressive dressing help to limit swelling in the first few days following the injury. Your doctor will prescribe a knee brace to help you safely return to walking without crutches under the direction of your physical therapist. The brace is typically worn for six weeks. Prior to returning to play, the knee should be re-examined to make sure that ligament has healed adequately. A special brace can be used to provide additional support when the player returns to sport.

Does an MCL tear require surgery?

Although many MCL injuries won’t require surgical treatment, a complete tear in the MCL where it attaches to the tibia is usually a candidate for surgery. The ligament does not generally heal well under these circumstances.

What is the surgery for an MCL tear?

When surgery is necessary, several options are available, including an MCL repair or a reconstruction of the ligament. If the ligament is reconstructed, either the patient’s own tissue or donor tissue is used to construct a new ligament. MCL repair surgery may result in better outcomes when it is performed within six weeks of the injury. The choice between which type MCL surgery, and the type of tissue used in the case of an MCL reconstruction will depend upon the injury itself as well as the preferences of the surgeon and patient.

What is the recovery time for MCL surgery?

Rehabilitation following MCL surgery is quite extensive. Patients will start physical therapy after surgery to first restore knee movement and muscle activation, and will then progress walking and strengthening, as the ligament heals and your surgeon approves more strenuous exercises. A recovery period of at least six months is often necessary prior to returning to vigorous exercise or competitive athletics.

Below, explore related content or (Find a doctor at HSS who treats MCL injuries.)

Articles on related issues

MCL Tear / MCL Injury of the Knee Success Stories

Updated: 6/7/2024

Reviewed and updated by Shevaun Mackie Doyle, MD; Claire D. Eliasberg, MD; Peter D. Fabricant, MD, MPH;

Daniel W. Green, MD, MS, FAAP, FACS; and Michelle E. Kew, MD

References

- Holuba K, Rilk S, Vermeijden HD, O'Brien R, van der List JP, DiFelice GS. Acute Percutaneous Repair of Medial Collateral Ligament With Suture Augmentation in the Multiligamentous Injured Knee Results in Good Stability and Low Rates of Postoperative Stiffness. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil. 2023 Oct 4;5(6):100799. doi: 10.1016/j.asmr.2023.100799. PMID: 37822672; PMCID: PMC10562670. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37822672/

- Chen L, Kim PD, Ahmad CS, Levine WN. Medial collateral ligament injuries of the knee: current treatment concepts. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2008 Jun;1(2):108-13. doi: 10.1007/s12178-007-9016-x. PMID: 19468882; PMCID: PMC2684213. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19468882/

- Marchant MH Jr, Tibor LM, Sekiya JK, Hardaker WT Jr, Garrett WE Jr, Taylor DC. Management of medial-sided knee injuries, part 1: medial collateral ligament. Am J Sports Med. 2011 May;39(5):1102-13. doi: 10.1177/0363546510385999. Epub 2010 Dec 8. PMID: 21148144. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21148144/

- Shultz CL, Poehlein E, Morriss NJ, Green CL, Hu J, Lander S, Amoo-Achampong K, Lau BC. Nonoperative Management, Repair, or Reconstruction of the Medial Collateral Ligament in Combined Anterior Cruciate and Medial Collateral Ligament Injuries-Which Is Best? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2024 Feb;52(2):522-534. doi: 10.1177/03635465231153157. Epub 2023 Mar 24. PMID: 36960920. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36960920/

- Westermann RW, Spindler KP, Huston LJ; MOON Knee Group; Wolf BR. Outcomes of Grade III Medial Collateral Ligament Injuries Treated Concurrently With Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Multicenter Study. Arthroscopy. 2019 May;35(5):1466-1472. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2018.10.138. Epub 2019 Mar 14. PMID: 30878328; PMCID: PMC6500749. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30878328/