Rotator Cuff Pain: Tendonitis/Tendinosis/Tendinopathy

Rotator cuff pain is quite common, and people become increasingly prone to experience the various conditions that cause it as they move into middle age (40s to 50s) and older.

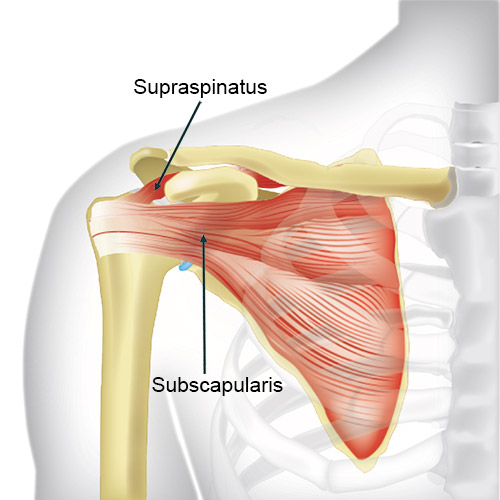

Rotator cuff anatomy

The rotator cuff is a group of muscles that surround the shoulder, stabilize it, and facilitate movement: The four rotator cuff muscles are the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis, and teres minor. Each rotator cuff muscle is connected to the humeral head (ball) by tendons and helps hold the ball of the shoulder joint securely in its socket while also enabling you rotate and lift your arm in different directions:

- The supraspinatus facilitates abduction – helping you lift your arm out to the side, especially in the beginning of that movement.

- The infraspinatus facilitates external rotation (the rotation of your arm outward at the shoulder) while keeping the ball of the joint securely in the socket, especially during certain strenuous activities like throwing or lifting.

- The subscapularis, the largest muscle of the rotator cuff, facilitates internal rotation of the arm at the shoulder. Its primary stabilizing function is securing the ball against the shoulder socket during pushing or lifting movements.

- The teres minor is adjacent to and below the infraspinatus and, like that muscle, helps with external rotation. It is much smaller, however, and more active toward the end of a rotation and/or when the arm is in certain positions, such as when it is raised at a significant angle away from the body.

Diagram of the anterior (front) of the shoulder, including the subscapularis and supraspinatus of the rotator cuff

Rotator cuff pain location

Rotator cuff pain can be felt throughout the shoulder but is often felt more to the lateral aspect (outside) of the shoulder. It often radiates down the upper arm to the elbow but does not typically radiate past the elbow. If pain radiates past the elbow or is more burning in nature and associated with tingling and/or numbness, this is more suggestive of pain coming from a pinched nerve, for example in the case of cervical radiculopathy or thoracic outlet syndrome.

What causes rotator cuff pain?

Rotator cuff pain is most commonly a chronic condition that arises from age-related degeneration and weakness in the rotator cuff and/or other muscles and tendons that support the shoulder, often in combination with overuse (repetitive stress). It can also be acute – for example, caused by a traumatic injury such as a fall, heavy lifting or forceful throwing. However, in most acute rotator cuff injury cases, underlying degenerative changes or other chronic issues played a role by leaving the rotator cuff more vulnerable to tears or strains.

Rotator cuff injuries almost always affect the tendons, rather than the muscles themselves, although in rare instances, a muscle injury can cause rotator cuff pain.

Pathologies associated with rotator cuff pain

Many patients may be understandably confused by the many names that may be used to describe chronic problems in the rotator cuff, such as “shoulder impingement syndrome,” “shoulder bursitis,” and “rotator cuff tendonitis.” These names are sometimes used interchangeably but in fact describe discrete conditions affecting particular anatomic structures in the shoulder – all of which are frequently associated with rotator cuff pain.

What may be even more confusing is that these specific conditions can overlap and one or more can be an underlying cause for another. For example, both shoulder impingement and shoulder bursitis can lead to rotator cuff issues. However, it is far more common for these conditions to result from an existing (and perhaps previously undetected) rotator cuff condition.

Conditions associated with the rotator cuff include:

- Shoulder impingement syndrome is a pinching or compression of a tendon.

- Shoulder bursitis is inflammation of a bursa in the shoulder, commonly the subacromial bursa that lies between the acromion – the bony tip at the top of the scapula, or shoulder blade and the supraspinatus tendon of the rotator cuff).

- Rotator cuff tendonitis is inflammation of a rotator cuff tendon

- Rotator cuff calcific tendonitis is a buildup of calcium deposits in the shoulder tendons that can cause local irritation and pain.

- Rotator cuff tendinopathy/tendinosis is degeneration and/or disorganization of rotator cuff tendon tissues (often due to overuse and repetitive activity).

The last of these are the terms doctors use most commonly today when issuing a diagnosis for rotator cuff disease. “Tendinopathy” (which indicates chronic degeneration of the tendon fibers) appears now to be a more accurate representation than “tendonitis” (where “-itis” refers to inflammation), which for decades was a commonly issued diagnosis. This is because although tendon inflammation may play a very early role in rotator cuff pain, examinations of chronically injured tendons under microscopes have not demonstrated there is actually much inflammation. Rather, when the rotator cuff tendons are repetitively used with inadequate periods of rest, they do not have time to adapt and heal, and the fibers that compose them become disorganized and degenerated (known as "tendinosis").

The current thinking by doctors is that tendon degeneration or disorganization (“tendinosis”) is the primary process. Chronic rotator cuff pain is now thought to be due more so to a failed healing response of the overloaded tendon, rather than an inflammatory process. In addition, it may be that tendon inflammation and degeneration (“tendonitis” and “tendinosis,” respectively) are actually two components of a singular process rather than separate processes.

What are the symptoms of rotator cuff tendinopathy?

Symptoms of rotator cuff tendinopathy typically develop gradually and can be chronic, lasting for months. These symptoms may include:

- pain around the shoulder – most commonly at the lateral (outside) shoulder and/or upper arm, but pain can also be in the front or back of the shoulder

- pain when raising or lowering the arm

- pain when reaching behind your back

- pain that gets worse after long periods of lying down on the affected side, which may disrupt sleep

- loss of strength and/or range of motion in the affected arm

When should I see a doctor for rotator cuff pain?

You should see a doctor if shoulder pain is affecting your daily life, waking you up from sleep or reducing your range of motion. Make an appointment to see a doctor if:

- Your shoulder hurts when you do the same activity over and over.

- You experience a loss in range of motion.

- You develop weakness in your shoulder.

- Shoulder pain awakens you from sleep.

- Shoulder pain is accompanied by swelling, redness, or tenderness around the joint.

What kind of doctor treats rotator cuff pain?

If you experience rotator cuff pain, you should see a physician with expertise in the shoulder. This could include a physiatrist (a doctor of physical medicine and rehabilitation), a primary sports medicine physician, or an orthopedic surgeon. Each has a slightly different background in training, with physiatrists and primary sports medicine physicians being nonsurgical doctors. Most rotator cuff conditions do not ultimately require surgery. If surgery is indicated, you would be referred to an orthopedic surgeon specializing in sports medicine.

How is the cause of rotator cuff pain diagnosed?

A doctor will first take your medical history and perform a physical examination to:

- Locate areas of shoulder pain or tenderness.

- Test the range of motion.

- Evaluate the strength of the shoulder muscles.

An X-ray may be ordered to evaluate other potential causes of shoulder pain (arthritis, calcific tendonitis), but an X-ray cannot diagnose rotator cuff tendinopathy.

If a rotator cuff tear is suspected, an ultrasound or MRI may be ordered. These tests can visualize the rotator cuff directly. However, rotator cuff tears can be asymptomatic, so if a rotator cuff tear is found on imaging, this does not mean that is always the source of your pain. Studies have shown there can be pathology including tears in the rotator cuff on imaging in patients without any shoulder pain or symptoms.

When diagnosing a shoulder cuff injury, a doctor will also rule out conditions that can cause similar symptoms, such as cervical radiculopathy (a pinched nerve in the neck) or shoulder arthritis.

How is rotator cuff tendinopathy treated?

The treatment begins by first controlling pain and improving range of motion, and then strengthening muscles. Relative rest is often recommended to try and avoid pain-provoking activities. However, you do not want to completely stop using the shoulder altogether, as this can lead to another condition called frozen shoulder. Intermittent icing of the shoulder, along with taking oral NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as ibuprofen or naproxen) for a brief period can be used initially to help with pain, but this does not “cure” the problem. This is usually followed by physical therapy, which is the mainstay of treatment for tendinopathy. This involves exercises to gradually strengthen and rehabilitate the rotator cuff muscles. It may take weeks to months though before the benefits from physical therapy are seen.

If all the above are tried but do not control symptoms after months, for rotator cuff tendinosis, other nonsurgical interventions may be tried.

Interventional procedures for rotator cuff tendinopathy

Your doctor may try one or more of the following therapies, a lot of which are still investigational in nature:

- A corticosteroid injection (“cortisone shot”). This may provide short term pain relief but does not “cure” tendinopathy. There is some concern cortisone may weaken muscle and tendon tissue, and this may not be an option if it is expected that you may need surgery in the near future.

- Percutaneous needle tenotomy: A needle is repetitively passed through the affected tendon to re-start the healing process.

- Extracorporeal shockwave therapy: Transcutaneous (through the skin) applications of sound waves directed at a targeted area within the body to promote healing and alleviate pain.

- Platelet-rich plasma (PRP injections). This involves isolating the growth factors from one’s own blood and injecting them into the tendon. HSS researchers are exploring the use of PRP and other orthobiologics (regenerative medicine for orthopedic conditions), but the results of their effectiveness for treating rotator cuff tendinopathy are mixed. More research is needed.

How long does rotator cuff tendinopathy take to heal?

The symptoms of rotator cuff tendinopathy can take months to improve.

What if rotator cuff tendinosis goes untreated?

Over time, if left untreated, the degeneration from rotator cuff tendinopathy can progress to tearing of the tendons either due to degenerative changes or acutely from a sudden stress or injury. However, not all degenerative rotator cuff tears cause symptoms or require treatment.

Articles on preventing rotator cuff pain and injury

Articles on rotator cuff pain treatment

Articles on related conditions and differential diagnoses

Rotator Cuff Pain: Tendonitis/Tendinosis/Tendinopathy Success Stories

Posted: 11/18/2024

Reviewed and edited by David A. Wang, MD, and Dena Barsoum, MD

References

- Eliasberg CD, Trinh PMP, Rodeo SA. Translational Research on Orthobiologics in the Treatment of Rotator Cuff Disease: From the Laboratory to the Operating Room. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2024 Mar 1;32(1):33-37. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0000000000000395. Epub 2024 May 2. PMID: 38695501. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38695501/

- Kirschner JS, Cheng J, Hurwitz N, Santiago K, Lin E, Beatty N, Kingsbury D, Wendel I, Milani C. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous needle tenotomy (PNT) alone versus PNT plus platelet-rich plasma injection for the treatment of chronic tendinosis: A randomized controlled trial. PM R. 2021 Dec;13(12):1340-1349. doi: 10.1002/pmrj.12583. Epub 2021 Apr 28. PMID: 33644963. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33644963/

- Puzzitiello RN, Patel BH, Nwachukwu BU, Allen AA, Forsythe B, Salzler MJ. Adverse Impact of Corticosteroid Injection on Rotator Cuff Tendon Health and Repair: A Systematic Review. Arthroscopy. 2020 May;36(5):1468-1475. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2019.12.006. Epub 2019 Dec 17. PMID: 31862292. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31862292/