Shoulder Impingement

What is shoulder impingement?

In general, shoulder impingement refers to cases in which tissue such as a tendon or bursa becomes (or pinched) compressed (“impinged”) around the shoulder joint.

The term “shoulder impingement syndrome” is sometimes used to describe a broader array of associated symptoms and related conditions of the shoulder. The word "syndrome" signifies a collection of symptoms and problems, which could include pain, swelling, inflammation, loss of mobility, and other complications like tendonitis or bursitis.

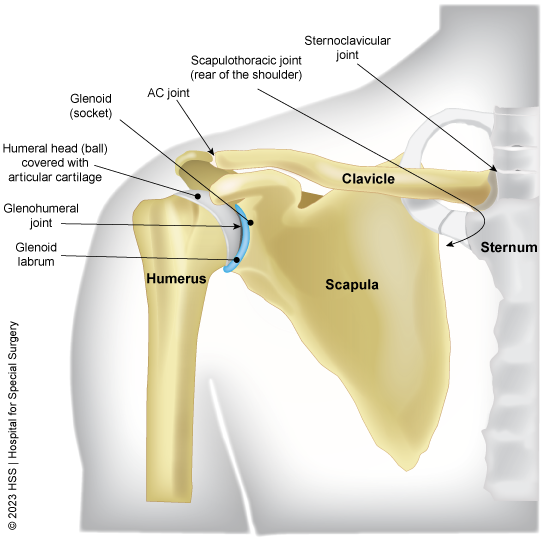

Before discussing the different types of impingements and their symptoms, it will help to get a brief understanding of the various structures of the shoulder.

Shoulder anatomy overview

The shoulder is a complex structure composed of three bones which meet at four joints, enabling you to lift, lower and rotate your arm in all directions.

The three bones that compose the shoulder are the humerus (upper arm), the scapula (shoulder blade), and the clavicle (collarbone). They form four separate joints:

- The glenohumeral joint is a ball-and-socket joint. The humeral head at the top of the humerus (upper arm bone) is the rounded ball that meets the socket, called the glenoid, which lies on the side of the scapula (shoulder blade).

- The sternoclavicular joint, at the top of the chest, connects the sternum (breastbone) with the clavicle (collarbone).

- The acromioclavicular joint (AC joint) is where the acromion (the upper rear tip of the scapula) meets the clavicle.

- The scapulothoracic joint is where the scapula glides across the rib cage in the back of the shoulder.

Illustration of the joints of the shoulder

There are various types of shoulder impingement, depending on which joint is involved, which tissues are compressed and the underlying causes of the compression.

What are the different types of shoulder impingement?

Many types are described, generally either by terms denoting their anatomic location (which bones or soft tissues are involved) or by their cause (which conditions or degenerative processes initiate or exacerbate the symptoms). We will review impingement causes further below, but the clearest method to explain specific subtypes of impingement is based on the anatomy involved. Various soft tissues can become compressed in the different joints that make up the shoulder.

Types of shoulder impingement by anatomic location

- Subacromial impingement: Sometimes also called “external impingement of the shoulder” or “subacromial impingement syndrome,” this is the most common type of shoulder impingement. In this form, a tendon or bursa (or both) may become compressed in the subacromial space between the top of the ball (humeral head) and the roof (acromion). Most commonly, it is the supraspinatus tendon of the rotator cuff that becomes impinged.

- Subcoracoid impingement: This type of impingement – close to the front of the axilla (AKA armpit) – is where the subscapularis tendon of the rotator cuff becomes pinched between the coracoid process (a bony protuberance at the front of the scapula) and the lesser tuberosity of the humerus below the humeral head.

- Internal shoulder impingement: Also called “internal ball impingement, this is where a tendon – usually the supraspinatus and/or infraspinatus tendon of the rotator cuff is pinched between the ball and the back of the shoulder socket, labrum can be pinched as well. This type is relatively rare and experienced mostly by professional throwing athletes (such as baseball pitchers) or in people whose occupations involve frequent heavy throwing. This type of impingement can sometimes also cause a glenoid labrum tear.

Anterior (frontal) view of subacromial and subcoracoid shoulder impingement locations. Location of internal impingement is primarily posterior (rear of the shoulder) and not shown.

What is rotator cuff impingement?

Rotator cuff impingement is a somewhat colloquial term that, typically, refers to subacromial impingement involving a rotator cuff tendon. The naming conventions above are more appropriate and descriptive.

What are the symptoms of shoulder impingement?

The most common symptoms of shoulder impingement are shoulder pain (especially while reaching or throwing overhead), stiffness, tenderness to the touch and/or weakness.

Pain may be sharp and localized (often during activity) or dull and diffuse (especially while lying down at rest). The location of the pain will depend on which type of impingement is present but is usually felt at the top or back of the shoulder.

When tingling is present, it most often is localized to the shoulder, but can radiate down the arm. This, however, is also a common symptom of cervical radiculopathy (a pinched nerve in the neck). These conditions can be mistaken for one another or – since they can involve adjacent tissues in the continuum of the neck and shoulder – even overlap. An accurate diagnosis is important.

What are the causes of shoulder impingement?

Broadly speaking, the causes of a shoulder impingement are structural (anatomic predisposition), functional (things you are doing with your shoulder) or, often, both. A subacromial impingement, for example, might be attributed to your anatomy – the shape of how the bones of your shoulder were formed at the time you stopped growing in adolescence or an anatomic abnormality such as a bone spur. On the other hand, it could be caused by something you are doing, whether that action is overuse (frequent or repetitive throwing or hyperextension) or underuse (lack of exercise) and poor posture or abnormal movements of your shoulder blade (scapula).

In addition, shoulder injuries and degenerative changes that become common as we reach middle age may trigger an impingement. For example, the subacromial space can become narrowed as a result of diseased or damaged soft tissue that lies within the space. Examples of this can include inflammation of the subacromial bursa (shoulder bursitis) or diseased or torn rotator cuff tendon. In fact, rotator cuff tendinosis is common and, on imaging, the tendons are shown to be thickened, essentially reducing the space) is the most common underlying cause of subacromial impingement. Although less common, the reverse can also be true: A subacromial impingement caused primarily by the particulars of a person’s anatomy can lead to a diseased rotator cuff tendon.

Even when anatomy plays a role, causation is often multifactorial. For example, variations of some people’s bone anatomy may make them more prone to impingement, but the impingement itself may arise only after a person develops an underlying condition, such as early-stage disease of the rotator cuff (tendinopathy). Age-related changes, namely degeneration of the tendons and bursa in the shoulder, make people more susceptible to tendinopathy, bursitis and other related conditions that can lead to impingement. When anatomic factors and age-related changes are then combined with various activities, the likelihood of shoulder impingement increases.

Activities that may trigger or exacerbate shoulder impingement include:

- Overuse: Repetitive arm movement – especially overhead arm movement – from athletic or occupational activity can lead to tendinopathy and resulting impingement.

- Underuse: Lack of exercise of the arm and shoulder weakens the muscles, which puts greater strain on tendons. This is especially the case when chronic underuse is followed by a sudden, short-term or prolonged overuse.

- Poor posture: Frequent slouching can alter the alignment of the shoulder joint and make one more prone to impingement.

- Scapular dyskinesis: This where the scapula moves into an incorrect position – often sticking out abnormally, causing faulty movement and, sometimes, impingement.

- Injury: Less often, an impact injury from a fall or direct blow to the shoulder can cause inflammation of soft tissues, which then become impinged inside a joint.

When these "bad habits" of faulty movement and poor posture are avoided, the risk of developing shoulder impingement is diminished.

How is shoulder impingement diagnosed?

Your doctor will diagnose shoulder impingement based on your medical history (typically the most important part of the intake and can lead to the right diagnosis), a physical examination and, usually, imaging tests such as an X-ray or MRI to confirm a diagnosis. The physical exam for shoulder impingement will likely include the following tests. If pain is felt during either, the diagnosis is positive:

- Neer impingement shoulder test: Your doctor will place your arm downward and hold your shoulder blade in place, then slowly lift your arm upward in a forward semicircle. Pain suggests impingement

- Hawkins-Kennedy test: The doctor will position your upper arm straightforward and perpendicular to your body with your elbow bent inward toward your chest at 90 degrees. Supporting your upper arm at the elbow, the doctor will then gently push down on your forearm to passively rotate your shoulder inward.

Imaging will often be ordered to distinguish symptoms from those in other conditions that may overlap with or be discrete from an impingement, such as shoulder arthritis, bursitis, rotator cuff tendinopathy and cervical radiculopathy.

What kind of doctor should I see for shoulder impingement?

If you experience shoulder pain that may be caused by an impingement, a good way to start is by consulting a physiatrist (a doctor of physical medicine and rehabilitation) or a sports medicine physician – such as a primary sports medicine doctor or an orthopedic surgeon who specializes in the shoulder. Each has a slightly different approach to patient care but often work in collaboration. Some are cross-trained, having done fellowships in both disciplines. Physiatrists are nonsurgical doctors, as are some sports medicine physicians. Other sports medicine physicians are also orthopedic surgeons to whom you may be referred if it is determined you have a rotator cuff tear that may benefit from surgery.

How is shoulder impingement treated?

The treatment for subacromial impingement depends on the severity of the condition. Mild cases may be treated by patient education, activity modification, resting and icing the shoulder, taking over-the-counter pain medication such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and undergoing physical therapy. (See also Exercises for Shoulder Impingement, from a PT.)

If these methods fail and/or in some more severe cases, injections of corticosteroids, platelet-rich plasma (PRP) or other agents may reduce inflammation and pain and improve function. In some cases, an arthroscopic shoulder surgery called subacromial decompression may be necessary to improve the space beneath the acromion.

How can you prevent shoulder impingement?

There are a number of things you can do to help prevent shoulder impingement, including:

- warming up before exercising

- stretching after exercising

- avoiding activities that put stress on your shoulders

- maintaining a healthy weight

- maintaining good posture and, for office workers, proper desk ergonomics and good movement patterns

- strengthening the muscles around your shoulder

- using proper weight training techniques to balance muscles

Learn more about prevention by reading Shoulder Muscle Anatomy: How to Strengthen and Avoid Injury.

Articles on surgical treatments for shoulder impingement

Shoulder Impingement Success Stories

Posted: 3/17/2025

Reviewed and updated by James F. Wyss, MD, PT

References

- De Martino I, Rodeo SA. The Swimmer's Shoulder: Multi-directional Instability. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2018 Jun;11(2):167-171. doi: 10.1007/s12178-018-9485-0. PMID: 29679207; PMCID: PMC5970120. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29679207/

- Eliasberg CD, Trinh PMP, Rodeo SA. Translational Research on Orthobiologics in the Treatment of Rotator Cuff Disease: From the Laboratory to the Operating Room. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2024 Mar 1;32(1):33-37. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0000000000000395. Epub 2024 May 2. PMID: 38695501. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38695501/

- Katsuura Y, Bruce J, Taylor S, Gullota L, Kim HJ. Overlapping, Masquerading, and Causative Cervical Spine and Shoulder Pathology: A Systematic Review. Global Spine J. 2020 Apr;10(2):195-208. doi: 10.1177/2192568218822536. Epub 2019 Feb 17. PMID: 32206519; PMCID: PMC7076593. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32206519/

- Lin KM, Wang D, Dines JS. Injection Therapies for Rotator Cuff Disease. Orthop Clin North Am. 2018 Apr;49(2):231-239. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2017.11.010. Epub 2017 Dec 19. PMID: 29499824. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29499824/

- Liu Y, Deng XH, Carballo CB, Cong T, Piacentini A, Jordan Hall A, Ying L, Rodeo SA. Evaluating the role of subacromial impingement in rotator cuff tendinopathy: development and analysis of a novel rat model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2022 Sep;31(9):1898-1908. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2022.02.041. Epub 2022 Apr 14. PMID: 35430367. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35430367/