Complex Patellofemoral Instability: A Collaborative Approach

Patellofemoral instability is a type of knee instability in which the kneecap slips partially out of place (subluxation) or dislocates completely. People with priror knee injuries may be at risk for this condition, and some are prone to it based on being loose-jointed or because of the particular anatomy of their patellofemoral joint. A person who has one of these conditions, as well as certain atypical leg bone formations may have what is known as complex patellofemoral instability.

What is complex patellofemoral instability?

Complex patellofemoral instability is a form of patellofemoral instability in which malformation of the bones (femur and tibia) around the patellofemoral joint cause imbalance, with potential increased stresses on the cartilage and ligaments, specifically on the medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL). This is different from the more common form of patellofemoral instability, in which there may be fewer and milder bone malalignments that do not place as much stress on the MPFL.

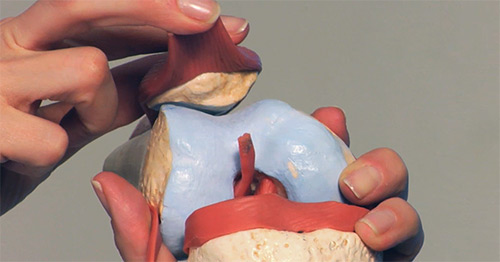

Patellofemoral joint anatomy

The patellofemoral joint of the knee is composed of two bones: the femur (thighbone) and the patella (kneecap). The kneecap rests and glides within a groove on the femur called the trochlea. The trochlea (also known as the sulcus or track) is located between two bony prominences known as the femoral condyles.

The joint is supported and stabilized by a complex network of ligaments, tendons and other soft tissues. In the healthy knee, these bones move smoothly and track in-line against one another as the joint is flexed (bent) or extended (straightened).

Diagram of the patellofemoral joint showing the location of the MPFL on the inside of the knee.

Diagram of the the patellofemoral joint showing other structures, including the medial collateral ligament (MCL) and patellar tendon.

In people with patellofemoral instability, the kneecap does not “track” properly and securely in the trochlea but slips out or tilts and subluxes (partially dislocates).

This slippage leads to frequent dislocations or subluxations of the patellofemoral joint.

- Subluxation is when the kneecap slips partially out of the femoral groove (trochlea).

- Dislocation is when the kneecap forcibly and completely displaces from the trochlea due to a high-impact injury, stretching or tearing a ligament on the inside of the knee called the medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL) in the process.

Common versus complex patellofemoral instability (PFI)

People with common PFI may naturally have loose ligaments and joints that put them at risk. In other patients, a patella tracking problem may begin with an initial traumatic injury during sports activity that causes a subluxation or dislocation, which can tear the ligament. Although it will heal, it will do so with more slack in it and leave the joint in a loosened condition thereafter.

But a person with complex patellofemoral instability also has a moderate or significant bone deformity in the thigh or leg which places increased stress on the joint, specifically on the MPFL. These stresses increase the likelihood that the kneecap will slip out of the track and makes the knee more prone to recurrent instability events and injury to the cartilage.

The two most common femoral malalignment problems that contribute to patellofemoral instability are knock knee (valgus) and rotational deformities (femoral anteversion). These femoral deformities may not be seen on routine X-rays or MRI, and often need a special type of CT scan. Leaving these deformities uncorrected may reduce the effectiveness of any patellofemoral surgery and may lead to ligament (MPFL) reconstruction failure and further dislocations.

Knock knee

Knock knee (genu valgum) is an alignment where one or both knees curve inward so that the knees touch. This positioning can increase the forces pulling the kneecap toward the outside of the knee and places greater stress on the MPFL.

Femoral anteversion

This is a rotational deformity in which the femur is twisted. Femoral anteversion refers to inward rotation of the knee relative to the hip joint. As the femur rotates inward, the patella is pulled outward, adding to the forces causing patellar instability. This can be unnoticed by patients and physicians alike. One sign of anteversion is in-toeing and another is “squinting” kneecaps. The tibias may rotate outward to compensate for the anteversion, which adds further to the complexity of this condition.

Figure: Anteroposterior (front-to back) X-ray imaging of a knock-knee condition before and after realignment surgery. The figure at left shows a patient with knock knee malalignment of both legs. The blue lines demonstrate the weightbearing axis of the limbs, which should pass through the central portion of the knee. Valgus alignment places excessive stresses on the outer portion of the knee, leading to joint damage and osteoarthritis. The patellas (kneecaps) are being pulled out of the center of the knee joint as well. The figure on the right shows the same patient after correction of valgus with normal weightbearing axes and central positioning of the kneecaps.

How do I know if I have complex patellofemoral instability?

Signs and symptoms include:

- Having multiple known or suspected subluxations or dislocations of the kneecap.

- Feeling like your leg or kneecap is crooked or twisted. (Patients sometimes say “my knees look weird” or “look strange” but are not sure why.)

- Failed previous patellar surgery.

How do you treat complex patellofemoral instability?

Various surgical combinations may be performed, depending on the particular anatomy and condition of each patient.

Treatment begins with a comprehensive evaluation, including a physical exam, specialized knee radiographs:

- standard knee X-rays, including a “Merchant X-ray”

- standing hip-to-ankle alignment X-rays

- a knee MRI

- a CT study to assess any malalignment of the femur

In addition, a diagnostic knee arthroscopy will be done at the time of surgery. This serves to complete the evaluation of the knee joint.

Complex PFI describes a ring of problematic conditions that surround the patella. The best way to treat these combined issues is to address them in 360-degree arc. This is referred to as the Patellofemoral 360 (PF360) procedure and includes:

- distal femoral realignment osteotomy (DFO)

- MPFL reconstruction

- tibial tubercle transfer (TTT) osteotomy

- surgical lengthening of the iliotibial band (IT band) or, in some cases, lateral retinaculum (fibrous tissue on the outer side of the kneecap)

Additional procedures performed during knee arthroscopy may include cartilage restoration procedures if significant damage exists from the previous dislocations.

Before-and-after illustration of an MPFL reconstruction surgery.

Surgical collaboration to address complex cases

The need by many patients for this combination of unique surgeries led to a collaboration by two HSS surgeons, who bring their specific skill sets together to deliver comprehensive surgical treatments.

Beth Shubin Stein, MD, is a sports medicine physician and orthopedic surgeon in the Sports Medicine Institute at HSS and cofounder of the Patellofemoral Center who focuses on arthroscopic and reconstructive surgery of the patella for instability and for cartilage damage and arthritis. Austin T. Fragomen, MD, a surgeon on the Limb Lengthening and Complex Reconstruction Service (LLRCS), is an expert in skeletal reconstruction of the limbs.

Common patellofemoral instability is typically treated by sports orthopedists, while limb deformity correction is a specialty of the LLCRS surgeons. Although specialization in orthopedics means that surgeons become top experts for specific conditions, this kind of hyperspecialization can also have a downside for treating patients with complex conditions that cut across those specialties. To address this, our interdisciplinary surgical approach integrates the otherwise unrelated skill sets to foster innovation in how we think about, evaluate, and treat complex PFI with the PF360 approach.

The collaboration developed after numerous mutual referrals between the two surgeons. On numerous occasions, each surgeon had a patient they were treating who had a coexisting condition which could benefit from the expertise of other.

A specialist in patellofemoral conditions, Dr. Shubin Stein sees a high volume of patients who have patellar instability. Many have had prior surgeries that have failed to stabilize their kneecap. Both clinical experience and scientific research help the two surgeons understand that these surgeries alone failed to adequately address these patients’ patellofemoral instability because there were undiagnosed or underappreciated limb deformities.

Multiple surgeries at one time

A key benefit of this collaboration is that Dr. Shubin Stein and Fragomen work together on each patient during one scheduled day of surgery. This means the patient receives anesthesia only once and spends less time in the hospital. Some other institutions offer similar collaborative approaches, but the individual surgeries are planned to be months or even years apart.

Drs. Fragomen and Shubin Stein have made this possible at HSS by adapting their surgical methods to align with each other’s work – addressing all of the patient’s problems at once.

Working together in this way, the surgeons have innovated a novel surgical approach that is tailored to each patient’s particular anatomy and condition, and which has become routine, proven and safe.

Many patients require bilateral (both knees) patellofemoral reconstruction surgery. In these cases, each leg is treated on separate occasions. This ensures that patients remain mobile and independent during the entire recovery period, since they always have a good leg to stand on. This postoperative mobility is important to speed up rehabilitation and avoid complications.

How long will I stay in the hospital?

This may depend on your pain control and progress with physical therapy, but patients typically stay two to three nights in the hospital.

How long does it take to recover from surgery for complex patellofemoral instability?

Since the exact combination of procedures varies from patient to patient, each case is slightly different. Patients will be off crutches and out of a brace in three months. It will generally be 9 to 12 months before you can return to full sports activity.

What is the recovery like?

Recovery involves a mix of weightbearing restrictions, medications and bracing, followed by several months in a physical therapy program.

Weightbearing

- No weightbearing for the first four weeks.

- Most patients will be fully weightbearing in 6 to 10 weeks.

Physical therapy

For the first four weeks after surgery, you will do a home exercise program that focuses on increasing your range of motion and strengthening your quadriceps muscle.

After four weeks, an HSS physical therapist will evaluate your progress, help you start weightbearing, and provide additional home exercises.

At six weeks after surgery, you will begin a formal physical therapy programs with a rehabilitation specialist. Physical therapy will be twice a week for 8 to 12 months. Complete dedication to and attendance of your rehab sessions are critical to successful recovery.

Posted: 4/20/2021

Authors

Orthopedic Director, Women's Sports Medicine Center, Hospital for Special Surgery

Attending Orthopedic Surgeon, Hospital for Special Surgery

Attending Orthopedic Surgeon, Hospital for Special Surgery

Director, Limb Salvage and Amputation Reconstruction Center, Hospital for Special Surgery

Related articles

References

Liu JN, Steinhaus ME, Kalbian IL, Post WR, Green DW, Strickland SM, Shubin Stein BE. Patellar Instability Management: A Survey of the International Patellofemoral Study Group. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46(13):3299-3306. doi:10.1177/0363546517732045.