Rotator Cuff Tear

The shoulder is composed of three bones that, together, form four joints. (Visit this page to see an illustration of the shoulder bones). The largest of these joints, which allows the upper arm to rotate, is the glenohumeral joint. It is a ball-and-socket joint formed where the humeral head (ball) at the top of the humerus (upper arm bone) meets the glenoid (socket). This socket is much shallower than that in other ball-and-socket joints like the hip. For this reason, the shoulder joint relies heavily on the rotator cuff and other structures to help stabilize it. Tears in the rotator cuff can cause shoulder pain, weakness and instability.

What is the rotator cuff?

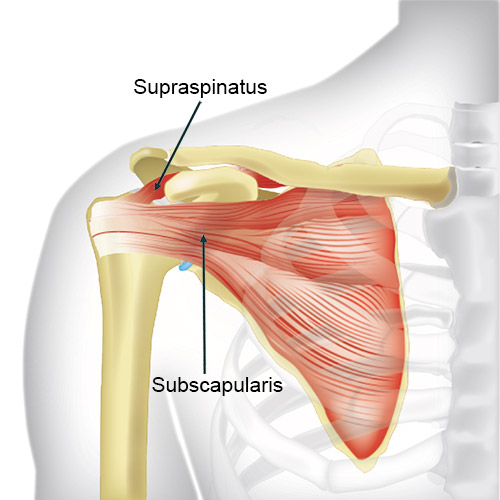

The rotator cuff is a group of muscles that surround the shoulder, stabilize it, and facilitate movement: The four rotator cuff muscles are the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis, and teres minor. Each rotator cuff muscle is connected to the humeral head (ball) by tendons and helps hold the ball of the shoulder joint securely in its socket while also enabling you rotate and lift your arm in different directions:

- The supraspinatus facilitates abduction – helping you lift your arm out to the side, especially in the beginning of that movement.

- The infraspinatus facilitates external rotation (the rotation of your arm outward at the shoulder) while keeping the ball of the joint securely in the socket, especially during certain strenuous activities like throwing or lifting.

- The subscapularis, the largest muscle of the rotator cuff, facilitates internal rotation of the arm at the shoulder. Its primary stabilizing function is securing the ball against the shoulder socket during pushing or lifting movements.

- The teres minor is adjacent to and below the infraspinatus and, like that muscle, helps with external rotation. It is much smaller, however, and more active toward the end of a rotation and/or when the arm is in certain positions, such as when it is raised at a significant angle away from the body.

Diagram of the anterior (front) of the shoulder, including the subscapularis and supraspinatus of the rotator cuff

When the rotator cuff muscles and tendons work well together, they allow the shoulder to move smoothly and stay stable. But when a rotator cuff muscle or tendon gets injured or torn, it can lead to pain, shoulder weakness, and decreased function.

What is a rotator cuff injury?

Rotator cuff injuries are common and range in type and severity. They more frequently occur in the tendons rather than the muscles themselves but can include muscle or tendon strain, tendonitis, tendinosis or partial or complete rotator cuff tendon tears. Of these injuries, complete tears are the most severe, but the least common.

What is a rotator cuff tear?

A rotator cuff tear is a tear in any one of the tendons of the rotator cuff. It is the most common upper extremity condition seen by primary and sports medicine doctors and orthopedic surgeons. Only rarely does a tear occur in the muscle itself. However, a rotator cuff muscle strain is sometimes associated with an acute rotator cuff tendon tear.

The most commonly torn structure in the rotator cuff is the supraspinatus tendon. But tears can occur in the infraspinatus, subscapularis or teres minor. Teres minor tears are the least common and most often occur in conjunction with a tear of one of the other tendons.

What are the different types of rotator cuff tears?

Rotator cuff tears are classified based on their size – whether they are partial or complete. A partial rotator cuff tear (also known as partial thickness tear) is where some but not all of the fibers that compose a tendon are frayed or damaged. A full-thickness rotator cuff tear is a complete tear of the tendon – in which it tears either off from its insertion at the bone or transversely (across) through the tendon itself. This is most often a nontraumatic (chronic) rotator cuff injury, although a fall or other trauma can cause a full-thickness tear. There are several classification systems for rotator cuff tears that help guide treatment options.

Partial rotator cuff tear

Partial tears are commonly divided into three grades according to the Ellman classification, based on the amount of tendon tissue that torn where it meets the bone:

- Grade 1: Less than 3 mm (25% thickness)

- Grade 2: Sized 3 to 6 mm (25% to 50% thickness)

- Grade 3: Larger than 6 mm (50% thickness)

Full thickness rotator cuff tear

Complete rotator tears are most often divided into four categories using the Codman classification, based on the size of the tear from front to back (anterior to posterior). These are:

- Small: 0 to 3 cm

- Medium: 1 cm to 3 cm

- Large: 3 cm to 5 cm

- Massive: Greater than 5 cm, as well as tears involving more than one tendon

Muscle atrophy and retraction

Rotator cuff tears are further classified by muscle atrophy – which indicates the length of time a tendon has been torn – and, in tears where the tendon has pulled away (retracted) from the bone, the distance of retraction from its original insertion point on the bone.

What causes a rotator cuff tear?

A minor, partial tear can occur over time from overuse, or prolonged wear and tear (degeneration). Partial tears can progress to full-thickness rotator cuff tears over time. Complete ruptures can also be caused by a trauma such as dislocating your shoulder or by performing a sudden and heavy lift. It is a common injury among weightlifters, for example. A direct impact during sports, an industrial accident, or auto collision can also tear the rotator cuff.

When trauma is the immediate cause of a tear, it is often the case that existing tendon degeneration or a prior, less severe rotator cuff injury has played a contributing role.

What are the risk factors for a rotator cuff tear?

Several factors increase the risk of tearing the rotator cuff, with age being the most significant contributor. People over 40 often experience tendon degeneration, and genetics may also play a role, as rotator cuff issues can run in families. Men are at slightly higher risk than women, though the reason is unclear.

Athletes and people with jobs requiring frequent overhead arm movements (like baseball players, carpenters, or house painters) are at higher risk due to repetitive stress on the tendons. Poor posture and desk ergonomics can also contribute to this stress.

Smoking negatively impacts tendon health and healing, while conditions such as obesity, which leads to muscle atrophy, can increase tendon stress. Other factors like type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, and inflammatory disorders (such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus) are linked to higher rates of rotator cuff tears, though the exact causes are not always known.

What are the signs and symptoms of a torn rotator cuff?

Rotator cuff tear symptoms include:

- feeling pain:

- in the front and/or down the outside of the shoulder

- in the shoulder at night

- when the arm is moved in certain ways

- having trouble raising the arm

- experiencing weakness in the shoulder

- being unable to lift things

- hearing clicking or popping when the arm is moved

Sharp pain is usually felt in cases of an acute, traumatic tear. But regardless of cause, rotator cuff pain from a tear may be sharp and isolated (especially while reaching upward) or dull and diffuse (especially at night during long periods of rest or upon waking up from sleep).

How is a rotator cuff tear diagnosed?

A doctor will first take your medical history, discuss your symptoms, and perform a physical examination. Depending on the symptoms you describe, the physical examination will involve one or more rotator cuff injury tests to locate areas of tenderness, evaluate the range of motion, and determine the movements which cause pain and weakness. If tests suggest a rotator cuff injury, imaging may be ordered to confirm the diagnosis.

Rotator cuff injury test types

Which tests are performed may depend, in part, on whether your suspected rotator cuff injury is in the supraspinatus, subscapularis, or infraspinatus. and to determine whether the tendons that lie between the humerus and the acromion are being pinched (known as shoulder impingement).

Supraspinatus and infraspinatus injury tests

- Jobe test (also known as the empty can test): Your doctor will raise your arms frontward 90 degrees and outward about 30 degrees, then rotate your arms inward until your thumbs point down at the floor and push gently down on your arms as you try to resist. If you feel pain or weakness is detected, this indicates a supraspinatus tear.

- Drop arm test: This is to test for a full-thickness rotator cuff tear of the supraspinatus or, less often, the infraspinatus tendon. Your doctor will lift your arm sideways to 90 degrees with your palm facing forward, then let go. If your arm drops suddenly or you are unable to lower your arm in a controlled movement, the test is positive.

- Infraspinatus injury test: With your elbow bent 90 degrees at your side, your doctor will push inward while you resist. Alternately, they may hold your forearm in place and ask you to try to rotate it outward. Pain or weakness suggests an infraspinatus injury.

Subscapularis injury tests

- Bear hug test: You will place the hand that corresponds to your affected shoulder on top of the opposite, unaffected shoulder and press down while the doctor tries to pull your hand away from your shoulder. Pain or weakness suggests a subscapularis tear.

- Lift off test: Your doctor will have you place your hand behind your lower back and attempt to lift it away from your lower back. Difficulty or pain indicates a subscapularis tear. If can do this effectively, your doctor may put resistance against your hand to test your muscle strength and assess whether a less severe condition may be present.

Tests for shoulder impingement

Pain occurring during either of these tests suggests there is a shoulder impingement:

- Neer impingement test: Your doctor will place your arm downward and hold your shoulder blade in place, then slowly lift your arm upward in a forward semicircle. Pain suggests impingement

- Hawkins-Kennedy test: The doctor will position your upper arm straightforward and perpendicular to your body with your elbow bent inward toward your chest at 90 degrees. Supporting your upper arm at the elbow, the doctor will then gently push down on your forearm to passively rotate your shoulder inward.

Diagnostic imaging for rotator cuff tears

If the physical exam suggests you may have a torn rotator cuff, your doctor may order magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a musculoskeletal ultrasound, and/or an X-ray. An MRI is usually the most accurate type of diagnostic imaging for rotator cuff tears. It may confirm a tear diagnosis or indicate separate condition causing shoulder pain, such as compressed nerve in the neck (cervical radiculopathy). X-rays do not reveal tendon injuries but they visualize bones connecting them to rule out other conditions that can cause similar symptoms, such as shoulder arthritis.

How is a rotator cuff tear treated?

A mild rotator cuff tear may be treated nonsurgically with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen, corticosteroid injections and/or isometric exercises and physical therapy. HSS researchers are exploring the use of orthobiologics (regenerative medicine for orthopedic conditions) such as PRP injections, but the results of their effectiveness for treating rotator cuff tendinopathy or partial-thickness tears are mixed.

For complete tears and even some partial tears, surgery is often recommended, especially for active individuals who engage in sports or overhead work. Various surgical techniques, such as tendon repair or acromioplasty, may be applicable. In certain severe tears, and in cases where a person also has shoulder arthritis, a reverse shoulder replacement surgery may be warranted.

Articles on rotator cuff injury prevention

Articles related to treatments for rotator cuff injuries

Find articles and videos on surgical and nonsurgical treatments for rotator cuff injuries.

Rotator Cuff Tear Success Stories

Updated: 9/30/2024

Reviewed and updated by Claire D. Eliasberg, MD; Michelle E. Kew, MD; Madeline Kratz, PA-C, MMSc.

References

- Apostolakos JM, Brusalis CM, Uppstrom T, R Thacher R, Kew M, Taylor SA. Management of Common Football-Related Injuries About the Shoulder. HSS J. 2023 Aug;19(3):339-350. doi: 10.1177/15563316231172107. Epub 2023 May 20. PMID: 37435133; PMCID: PMC10331269. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37435133/

- Bedi A, Bishop J, Keener J, Lansdown DA, Levy O, MacDonald P, Maffulli N, Oh JH, Sabesan VJ, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Williams RJ 3rd, Feeley BT. Rotator cuff tears. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2024 Feb 8;10(1):8. doi: 10.1038/s41572-024-00492-3. PMID: 38332156. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38332156/

- Eliasberg CD, Trinh PMP, Rodeo SA. Translational Research on Orthobiologics in the Treatment of Rotator Cuff Disease: From the Laboratory to the Operating Room. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2024 Mar 1;32(1):33-37. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0000000000000395. Epub 2024 May 2. PMID: 38695501. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38695501/

- Herzberg SD, Zhao Z, Freeman TH, Prakash R, Baumgarten KM, Bishop JY, Carey JL, Jones GL, McCarty EC, Spencer EE, Vidal AF, Jain NB, Giri A, Kuhn JE, Khazzam MS, Matzkin EG, Brophy RH, Dunn WR, Ma CB, Marx RG, Poddar SK, Smith MV, Wolf BR, Wright RW. Obesity is associated with muscle atrophy in rotator cuff tear. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2024 Jun 28;10(2):e001993. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2024-001993. PMID: 38974096; PMCID: PMC11227827. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38974096/