Antiphospholipid Syndrome

A “syndrome” is a collection of signs and symptoms that are characteristic of a particular disorder. Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS, and also sometimes referred as antiphospholipid antibody syndrome), is a complex condition that is so named because its symptoms are caused by a dysregulated immune system that attacks the natural and healthy phospholipids produced in a person’s body.

What is antiphospholipid syndrome?

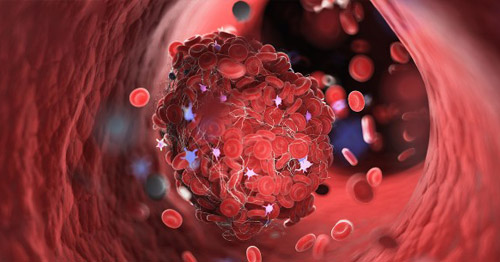

Antiphospholipid syndrome is a systemic autoimmune inflammatory disorder in which a person’s immune system makes antibodies that can cause the formation of blood clots in the blood vessels as well as pregnancy problems. Blood clotting (thickening of the blood) is a normal function of the body. It is what stops the bleeding when we get a cut. But blood clots that form inside the blood vessels are dangerous, and the overactive blood clotting associated with APS can cause life-threatening health problems.

A healthy immune system helps the body fight disease. It makes proteins called antibodies that identify and attack substances (called antigens) that enter the body and which might cause harm. The immune system of a person with APS misidentifies a substance that naturally occurs in our blood cells. It then makes antibodies that fight these “autoantigens” (antigens that are not from external sources). In other words, the body attacks itself. The main autoantigens associated with APS are phospholipids.

What is a phospholipid?

A phospholipid is a type of fat molecule that is the main building block of the outside layer of cell membranes. This is the case for bacteria and virus cells, but also in human cells.

What are antiphospholipid antibodies?

Antiphospholipid antibody (aPL) describes antibodies that attack certain proteins that bind the phospholipid cell walls of blood cells located on the inner layer of the arteries or veins. These antibodies are generally detected by three tests, namely: lupus anticoagulant (LA), anticardiolipin antibody (aCL), and anti-Beta-2-glycoprotein-I antibody (aβ2GPI). All of these create enhanced risk for blood clotting.

The terminology used to discuss APS can be confusing. There is an important difference between the terms “antiphospholipid antibody” (aPL) and “antiphospholipid syndrome” (APS). A positive aPL test alone, even in high levels, does not necessarily mean that a person has APS. Adding to this confusion is that there are several aPL tests, as discussed further below.

Does antiphospholipid syndrome cause all blood clots?

No. There are many other causes of blood clots. Deep vein thrombosis (DVT), for example, can occur in anyone who is sedentary for long periods of time, such as during a long airplane flight or after surgery. There are also many non-APS conditions and genetic factors that can make a person more susceptible to forming clots, including some cancers and inherited mutations or protein deficiencies. People who use nicotine and/or who have a history of high blood pressure or high cholesterol are also at accelerated risk for clots.

How common is antiphospholipid syndrome?

Epidemiology studies range widely, with APS affecting anywhere between 0.001% to as many as 0.05% of people. About 10% of people who have no autoimmune disease may experience isolated or temporary, low-titer positive tests for antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL) without having APS. Persistent, high-titer aPL positivity is found in about 1% to 2% of people with no other systemic autoimmune diseases. Clinically significant aPL is much higher in people with other autoimmune diseases. About 20% to 30% of people with lupus, especially, have clinically significant aPL positivity for aPL. Clotting risk in these patients is higher but still low (less than 4% per year).

What causes antiphospholipid syndrome?

As with other systemic autoimmune diseases, it is not known exactly why the body makes these abnormal autoantibodies that cause APS. Researchers hypothesize that environmental factors, such as infections, trigger the production of these antibodies in the immune systems of people who may have some genetic predisposition. There is also evidence of a connection between having a gut microbiome that is unhealthy or less diverse than average and developing antiphospholipid syndrome.

Is antiphospholipid syndrome contagious?

No. Although doctors don’t yet understand how or why people get the antiphospholipid antibodies, we do know that they do not spread like an infection.

What are the symptoms of antiphospholipid syndrome?

The primary symptoms of antiphospholipid syndrome are blood clots in the veins of the legs or arms, strokes (disruption of blood supply in part of the brain) and pregnancy problems such as miscarriage or pre-eclampsia. However, there are many other possible symptoms, including anemia or heart valve disease. On the other hand, some people whose bodies produce antiphospholipid antibodies (called being “aPL-positive”), develop no symptoms or APS-related health problems. Finally, other symptoms can appear as a result of the blood clots associated with APS, for instance leg swelling. Some people may have only one of these symptoms, while others have several of them. (See below for health problems associated with blood clots.)

Who is at risk for antiphospholipid syndrome?

Antiphospholipid syndrome can occur in otherwise healthy individuals, or in patients with other autoimmune disorders. It is not known why. APS can occur on its own, but it is often found in patients who have other autoimmune disorders, especially systemic lupus erythematosus (commonly known as "lupus").

Among people with no other systemic autoimmune disease, APS affects males and females about equally. Among APS patients who also have lupus, about 70% to 80% are women. This is largely because lupus itself affects women much more so than men. APS is more common among people with primarily White or Asian descent than in people with African descent.

Can children get antiphospholipid syndrome?

Yes, APS that appears during childhood or adolescence is called pediatric antiphospholipid syndrome. A rarer form, known as neonatal antiphospholipid syndrome, is present at birth or develops within the first month after a baby is born and most often fades away after several weeks. Neonatal APS most often results from the passage of autoimmune antibodies from an aPL-positive mother to the child through the placenta. There have been cases, however, that were spontaneous.

What health problems do APS blood clots create?

Blood clots in the arteries or veins (sometimes on a microvascular level) caused by antiphospholipid antibodies can create a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism as well as high blood pressure, heart attack, stroke, miscarriages, and many other problems. APS blood clot health complications include the following:

- Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (a blood clot in a lung): DVTs are a common risk after surgery, even for healthy people. For this reason, a person who has APS must take special precautions before having any kind of surgical procedure. Learn more about preventing blood clots when you have APS.

- Hypertension, (high blood pressure), heart attack, stroke, or kidney disease.

- Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS). In this condition, experienced by less than 1% of people with APS, multiple blood clots form in small, medium and large blood vessels over a short period of time (usually within a week). This life-threatening condition requires immediate hospitalization in an intensive care unit (ICU). The risk for blood clots increases whenever any patient is recovering from surgery. (Learn more about CAPS.)

- Miscarriage (pregnancy loss).

- Livedo reticularis, lace-like or marbled skin rashes, especially in the arms or legs

- Vision problems, dementia or cognitive dysfunction (any of which can arise due to stroke, when a blood clot blocks or reduces blood flow to parts of the brain).

Does antiphospholipid syndrome cause hardening of the arteries?

Doctors used to think so, but there now appears to be no correlation between APS and hardening of the arteries.

Can antiphospholipid syndrome turn into lupus?

Yes, rarely. About 50% of people with APS have “primary APS.” They may experience blood clots and/or have pregnancy problems, and they are less likely to develop another autoimmune disease. Although 30% to 40% of lupus patients test positive for antiphospholipid antibodies, most people with both diseases develop them at the same time. In addition, some APS patients may develop lupus-like symptoms such as joint pain and fatigue, even if they do not have full lupus.

Is it safe to become pregnant if I have antiphospholipid syndrome?

Women who have antiphospholipid syndrome are more likely to develop pregnancy complications, including miscarriages, preterm delivery (before 37 weeks), preeclampsia and eclampsia intrauterine growth restriction (reduced fetus size), and blood clots occurring while they are pregnant.

However, with appropriate monitoring and treatment, most women with APS can have successful pregnancies. Under current management of planned pregnancies, 80% of women with APS will deliver live newborn babies, and approximately 60% will have no pregnancy complications at all. (Learn more about APS and pregnancy or explore our relevant, ongoing clinical trials.)

Can I pass antiphospholipid syndrome on to my children?

Antiphospholipid syndrome is not currently believed to be directly inherited. However, it does seem to run in families. In a rare form known as neonatal APS, antiphospholipid antibodies may be passed through the placenta from mother to child. These antibodies in the infant tend to disappear within the first six months of life, and APS-caused blood clots in babies are extremely rare.

Antiphospholipid syndrome patients with other systemic autoimmune diseases are usually women; the female predominance is less obvious in primary APS patients. Antiphospholipid antibodies can be detected in approximately 15% of all stroke patients in the general population, 10% of heart attacks (myocardial infarction) and blood clots in large veins, and 9% of recurrent miscarriages.

How is antiphospholipid syndrome diagnosed?

There are no diagnostic criteria for APS. If a person has signs and symptoms that suggest they have APS, laboratory tests are ordered to determine the presence of antiphospholipid antibody (aPL). A conclusive diagnosis requires positive results from at least two such blood tests, spaced three or more months apart.

Because many symptoms of APS, including miscarriages, may be caused by other, more common conditions, many patients go undiagnosed for years. Adding to this confusion, people with APS sometimes receive a false-positive test result for syphilis, a sexually transmitted disease. On the other hand, there is also a problem with overdiagnosis: Some people are incorrectly diagnosed with APS, based solely on a single positive test for (aPL), which can occur frequently in healthy people. (Learn more by reading Classification Versus Diagnosis of Antiphospholipid Syndrome: How Are They Different?).

What is the blood test for antiphospholipid syndrome?

There are three blood tests which can confirm a diagnosis of APS if strongly positive results are consistent when two or more tests are performed at least 12 weeks apart:

- lupus anticoagulant test

- anticardiolipin antibody (aCL) IgG or IgM

- anti-Beta-2-glycoprotein-I antibody (aβ2GPI) IgG or IgM

About 10% of people who have no autoimmune disease may experience isolated or temporary, low-titer positive tests for antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL) without having APS. Persistent LA and/or high-titer aCL/aβ2GPI positivity is found in about 1% to 2% of people with no other systemic autoimmune diseases. This is considered “clinically significant”, meaning that a person may have APS. Clinically significant aPL is much higher in people with other autoimmune diseases. About 30% to 40% of people with lupus, especially, have clinically significant positivity for antiphospholipid antibodies. Clotting risk in these patients is higher but still low (less than 4% per year).

What kind of doctor treats antiphospholipid syndrome?

The primary specialist a person with APS should see depends on the symptoms with which they present. For example, hematologist may be consulted after a deep vein thrombosis, neurologist after stroke, or an obstetrician after a miscarriage. Because many people with APS also have other systemic autoimmune diseases (such as lupus), a rheumatologist may be consulted to help manage care. Patients should encourage continual dialogue between their primary care physician (family doctor) and any APS specialists they consult.

Even among specialist physicians such as hematologists or rheumatologists, only some actively manage antiphospholipid syndrome, while others may focus on other diseases. For this reason, it can be challenging to find appropriate APS specialists in some areas. (Find a doctor at HSS who treats APS, or search your area if you live outside the greater New York City region.)

When should you see a specialist if you have antiphospholipid syndrome?

Anyone positive for antiphospholipid antibodies who experiences a blood clot, has a stroke, or who is pregnant or planning to become pregnant should consult a physician with expertise in APS as soon as possible. Given that APS is a systemic autoimmune disease, a rheumatologist is generally involved in the care of APS patients. However, depending on on which organ (or organs) are involved, other specialists also provide care to APS patients. For example, if blood clots are your only symptom, a hematologist experienced in APS can provide care.

Besides blood clots, some other indicators to see an APS specialist include having low platelet counts, certain types of anemia, heart valve disease, skin rash called livedo, and a false-positive syphilis test. Lastly, if you are aPL-positive and need to have surgery, you should consider including an APS specialist on your healthcare team as APS patients are at increased risk for blood clots when they undergo surgeries. Learn more about special precautions aPL-positive patients should take when having surgery.

What is the treatment for antiphospholipid syndrome?

APS patients with a history of blood clots are usually placed on a long-term plan of anticoagulant medications (commonly called “blood thinners”), such as aspirin, warfarin, or heparin. Other medications are used to treat a subgroup of APS patients. These include:

- Corticosteroids, such as prednisone.

- Immunosuppressive medications such as hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil). Learn more about immunomodulator treatments for APS.

- Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) infusion therapy, in which antibodies obtained from multiple healthy blood donors are injected into the patient.

For all people patients who are positive for antiphospholipid antibodies, regardless of whether they have had clot, it is essential to eliminate as many reversible risk factors as possible, such as using nicotine, taking oral contraceptive pills or hormone replacement therapy. Patients who have unrelated cardiovascular diseases such as high blood pressure or diabetes must take care to manage these conditions to reduce their risk for clots.

How long will I need treatment for antiphospholipid syndrome?

Any person who has had multiple blood clots due to APS will likely need to take anticoagulation medications for life in order to manage the disease. The need for permanent treatment will depend on each individual and their circumstances. Some people are positive for antiphospholipid antibodies but who have had no symptoms may not require treatment but should be monitored.

Antiphospholipid syndrome treatment, research and clinical trials at Hospital for Special Surgery

HSS is one of the leading medical centers in the United States for treating adults and children who have antiphospholipid syndrome. Clinicians in our Lupus and APS Center of Excellence provide the highest quality of care to enhance our patients’ lives, and our top APS physician researcher serves as a medical advisor to the APS Foundation of America. HSS is also a founding member of the APS ACTION International Clinical Database and Repository, an international body of clinician researchers dedicated to advancing the understanding and management of APS.

Active clinical trials for antiphospholipid syndrome

- APS ACTION (Antiphospholipid Syndrome Alliance for Clinical Trials and International Networking) International Clinical Database and Repository

- DARE-APS

- The IMPACT Study: IMProve Pregnancy in APS with Certolizumab Therapy

- PROMISSE: Predictors of Pregnancy Outcome: Biomarkers in Anti-Phospholipid Antibody Syndrome (APS) and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE)

- The Psychosocial Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Rheumatology Patient Experience

Get a deep dive on antiphospholipid syndrome topics from the articles below.

Antiphospholipid syndrome treatment articles

Read about the different treatment options available to antiphospholipid-antibody-positive (aPL+) patients.

Articles from the Top 10 series on APS and lupus

These articles discuss the top 10 points lupus and APS patients should know about various topics related to their conditions.

- Antiphospholipid Syndrome Terminology – Top 10 Series

- APS ACTION International Clinical Database and Repository – Top 10 Series

- Antiphospholipid Syndrome and Organ Damage – Top 10 Series

- Antiphospholipid Syndrome and Lung Disease

- Prevention of Blood Clots in Antiphospholipid Antibody-Positive Patients – Top 10 Series

- Antiphospholipid Syndrome and the Gut Microbiome – Top 10 Series

- Catastrophic Antiphospholipid Syndrome

- Microvascular Antiphospholipid Syndrome

- Antiphospholipid Syndrome (APS) and Cancer – Top 10 Series

- Antiphospholipid Syndrome and Skin Problems – Top 10 Series

- Antiphospholipid Syndrome (APS) and Pregnancy – Top 10 Series

- Antiphospholipid Syndrome Clinical Research at HSS: 2023 Update – Top 10 Series

- Surgical Procedures in Antiphospholipid Antibody-Positive Patients – Top 10 Series

- Antiphospholipid Syndrome and Potential New Treatments – Top 10 Series

Articles on related issues

Antiphospholipid Syndrome Patient Stories

In the news

Updated: 11/1/2023

Reviewed and updated by Doruk Erkan, MD, MPH.

References

- Barbhaiya M, Zuily S, Naden R, Hendry A, Manneville F, Amigo MC, Amoura Z, Andrade D, Andreoli L, Artim-Esen B, Atsumi T, Avcin T, Belmont HM, Bertolaccini ML, Branch DW, Carvalheiras G, Casini A, Cervera R, Cohen H, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Crowther M, de Jesús G, Delluc A, Desai S, Sancho M, Devreese KM, Diz-Kucukkaya R, Duarte-García A, Frances C, Garcia D, Gris JC, Jordan N, Leaf RK, Kello N, Knight JS, Laskin C, Lee AI, Legault K, Levine SR, Levy RA, Limper M, Lockshin MD, Mayer-Pickel K, Musial J, Meroni PL, Orsolini G, Ortel TL, Pengo V, Petri M, Pons-Estel G, Gomez-Puerta JA, Raimboug Q, Roubey R, Sanna G, Seshan SV, Sciascia S, Tektonidou MG, Tincani A, Wahl D, Willis R, Yelnik C, Zuily C, Guillemin F, Costenbader K, Erkan D; ACR/EULAR APS Classification Criteria Collaborators. 2023 ACR/EULAR antiphospholipid syndrome classification criteria. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023 Oct;82(10):1258-1270. doi: 10.1136/ard-2023-224609. Epub 2023 Aug 28. PMID: 37640450.

- Dabit JY, Valenzuela-Almada MO, Vallejo-Ramos S, Duarte-García A. Epidemiology of Antiphospholipid Syndrome in the General Population. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2022 Jan 5;23(12):85. doi: 10.1007/s11926-021-01038-2. PMID: 34985614; PMCID: PMC8727975.

- Erkan D. Expert Perspective: Management of Microvascular and Catastrophic Antiphospholipid Syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021 Oct;73(10):1780-1790. doi: 10.1002/art.41891. Epub 2021 Sep 7. PMID: 34114366.

- Erkan D, Unlu O, Lally L, Lockshin M. Antiphospholipid Syndrome: What Should Patients Know? In: Antiphospholipid Syndrome Current Research Highlights and Clinical Insights. International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies, Doruk Erkan, Michael Lockshin, eds. Springer eBook, Cham, Switzerland, 2017.

- Erton ZB, Erkan D. Treatment advances in antiphospholipid syndrome: 2022 update. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2022 Aug;65:102212. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2022.102212. Epub 2022 May 27. PMID: 35636385.

- Erton ZB, Sevim E, de Jesús GR, Cervera R, Ji L, Pengo V, Ugarte A, Andrade D, Andreoli L, Atsumi T, Fortin PR, Gerosa M, Zuo Y, Petri M, Sciascia S, Tektonidou MG, Aguirre-Zamorano MA, Branch DW, Erkan D; APS ACTION. Pregnancy outcomes in antiphospholipid antibody positive patients: prospective results from the Antiphospholipid Syndrome Alliance for Clinical Trials and InternatiOnal Networking (APS ACTION) Clinical Database and Repository ('Registry'). Lupus Sci Med. 2022 Jun;9(1):e000633. doi: 10.1136/lupus-2021-000633. PMID: 35701043; PMCID: PMC9198709.

- Garcia D, Erkan D. Diagnosis and Management of the Antiphospholipid Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018 May 24;378(21):2010-2021. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1705454. PMID: 29791828.

- Gkrouzman E, Peng M, Davis-Porada J, Kirou KA. Venous Thromboembolic Events in African American Lupus Patients in Association With Antiphospholipid Antibodies Compared to White Patients. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2022 Apr;74(4):656-664. doi: 10.1002/acr.24508. Epub 2022 Mar 3. PMID: 33171010.

- Sammaritano LR. Antiphospholipid syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2020 Feb;34(1):101463. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2019.101463. Epub 2019 Dec 19. PMID: 31866276.

- Sammaritano LR, Bermas BL, Chakravarty EE, Chambers C, Clowse MEB, Lockshin MD, Marder W, Guyatt G, Branch DW, Buyon J, Christopher-Stine L, Crow-Hercher R, Cush J, Druzin M, Kavanaugh A, Laskin CA, Plante L, Salmon J, Simard J, Somers EC, Steen V, Tedeschi SK, Vinet E, White CW, Yazdany J, Barbhaiya M, Bettendorf B, Eudy A, Jayatilleke A, Shah AA, Sullivan N, Tarter LL, Birru Talabi M, Turgunbaev M, Turner A, D'Anci KE. 2020 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Management of Reproductive Health in Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 Apr;72(4):529-556. doi: 10.1002/art.41191. Epub 2020 Feb 23. PMID: 32090480.

- Sammaritano LR, Levy RA. Obstetric Antiphospholipid Syndrome: What Should Patients Know? In: Antiphospholipid Syndrome Current Research Highlights and Clinical Insights. International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies, Doruk Erkan, Michael Lockshin, eds. Springer eBook, Cham, Switzerland, 2017.

- Sevim E, Willis R, Erkan D. Is there a role for immunosuppression in antiphospholipid syndrome? Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2019 Dec 6;2019(1):426-432. doi: 10.1182/hematology.2019000073. PMID: 31808842; PMCID: PMC6913487.